do it yourself, Greece, home computers, magazines, press, programming, software

Theodore Lekkas

tlekkas [a] phs.uoa.gr

PhD

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

Aristotle Tympas

tympas [a] phs.uoa.gr

Prof., PhD

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

Viittaaminen / How to cite: Lekkas, Theodore, and Aristotle Tympas. 2020. ”Global Machines and Local Magazines in 1980s Greece: The Exemplary Case of the Pixel Magazine”. WiderScreen 23 (2-3). http://widerscreen.fi/numerot/2020-2-3/global-machines-and-local-magazines-in-1980s-greece-the-exemplary-case-of-the-pixel-magazine/

The article suggests that skillful and laborious work has been necessary to make the supposedly global (universal, general purpose) computer usable locally. This local use was greatly facilitated by the publication of computer magazines, which offered instructions to (as well as reviews and comparisons of) technological products, introduced interactive columns that addressed pressing user questions, and featured updates on and advertisements of hardware, software and peripherals. The article focuses on an exemplary Greek home computing magazine, Pixel, which was devoted to tinkering with computer programs and software more generally. It was the most influential in regards to home computing and ushered in the emergence and development of key user communities. Pixel had the largest circulation and went a long way in popularizing the home computer in Greece and in shaping its definition.

Introduction

It is widely assumed that the digital computer is for our electronic era what the steam engine was for the late mechanical era and the AC generator was for the electrical era: the ‘global’, ‘universal’, ‘general-purpose’ machine par excellence. As such, it is supposed to be automatically usable in every context, without any work to adjust it to local use. It is supposed to be usable in every country after simply being ‘transferred’ to it, without any work to ‘domesticate’ it through extensive and skillful reconfiguration, especially from a software angle. We argue that this is not the case. Skillful and laborious work has been necessary to make the supposedly global computer usable locally. For example, in the Greek case, as we have already shown, one had to work substantially even to see Greek letters (fonts) in the screen or the print (Tympas, Tsaglioti, and Lekkas 2008; Dritsa, Mitropoulos, and Spinellis 2018). In this article, we elaborate further on the way personal computers – and, more specifically, home computers – were appropriated, localized and domesticated in Greece by focusing on the proliferation of Greek computing magazines in the 1980s. As our argument goes, computer magazines shaped the way home computers were introduced and used in Greece during this crucial decade.[1]

Home computers were introduced and became popular in Greece in the early 1980s, just like in the rest of the world. We know that three institutions/media ushered in this use: computer stores, user communities, and computer magazines (Lekkas 2017; Lekkas and Tympas 2019; Guerreiro-Wilson et al. 2004). In the Greek case, magazine articles were the dominant source of information for users (Lekkas 2017). They covered news, offered instructions to and comparative reviews of technological products, introduced interactive columns that addressed pressing user questions, and featured updates on and advertisements of hardware, software and peripherals.[2] Several of the early Greek publications focused on IBM-compatible office microcomputers, as well as home computers by various manufacturers. In the beginning, it was still unclear where and by whom microcomputers were to be used. Computers and their users were shaped in interaction throughout the fluid 1980s. This fluidity was carried over to the magazines devoted to computing technology.

In the present paper, we offer an introduction to the history of this fluidity by focusing on an exemplar home computing magazine, Pixel. We decided to single out Pixel for detailed presentation because, as we shall see, it was the most influential in regards to home computing: it had the largest circulation, it was focused on how to tinker with programming and software more generally, it ushered in the emergence and development of key user communities, and it went a long way in popularizing the home computer in Greece and in shaping its definition. We now know that software required skillful labor, the scarcity of which was responsible for a permanent ‘software crisis’ (Ensmenger 2003). Pixel emerged as a software-oriented publication that sought to address key dimensions of this crisis in Greece.

“When a demanding reader walked in”

The first computer magazines appeared in Greece in response to an increasing interest in the microcomputer, especially the home computer. They became popular due to their versatility in regards to the services they offered, their readability, and their low price (Lekkas 2017). International computer magazines were comparatively expensive. For example, the American magazine COMPUTE cost 750 drachmas in Greece in 1986 whereas the Greek MicroMad cost 180 drachmas. Moreover, the availability of international magazines was limited because their importing in Greece was irregular and in limited quantities. These factors made them practically inaccessible to many individual Greek users (MicroMad 1986, 136). Pixel was first published in October 1983, initially as a trimonthly insert to Computer for All, which had been first published only a few months earlier. The first issue covered October, November and December 1983. The second issue was already an independent publication, covering May and June 1984. Its cost was 150 Greek drachmas. It was subtitled the home-micro magazine. This subtitle is worth noticing, because it shows that it was the first Greek computer magazine to directly address users of home microcomputers.

In 1983, N. Manoussos, the general director of Compupress, publisher of Pixel and Computer for All (Computer για Όλους), two of the most popular Greek magazines in the field at the time, noted the rapidly expanding demand for free software for home computers in the form of program listings. It was this demand that pushed towards the publishing of magazines specialized in home computing (Retrovisions of 80s 2019). The program listings were basically commands that formed a microcomputer software program, which were printed as a list on a sheet of paper. The user could type these commands in the microcomputer and then run them to make the software work. The target audience of the listings was users who struggled to find affordable software to run. There were listings for recreational, educational and business uses of the computer.

As these listings could not fit in the pages of Computer for All, a separate publication was needed. According to Manoussos (1983, 3) Pixel was introduced after Computer for All readers expressed through their responses to a questionnaire a strong desire for much needed software, to be provided for free, in the form of program listings. Manoussos, who was personally in charge of both the “Letter from the Publisher” column in Pixel and the corresponding “Note from the Publisher” column in Computer for All, has explained that the publishing of Pixel represented “an attempt by Computer for All to cover the need of ready to use software for home/personal computers by offering listings you can type in your microcomputer to create a ‘library of software’ or to study and discover new programming techniques.” The need for program listings is captured in the following reminiscence by Manoussos (Retrovisions of 80s 2019):

“Computer for All was probably the first Greek magazine to include such listings. Given, however, that there was a limit in the pages of the magazine, its listings were referring only to the most popular computers, like Sinclair, Commodore, etc. For the same reason, computing magazines could only rarely publish more than 2-3 programs per issue for the same machine. We were always under pressure by the readers to cover the home computer that they happened to have or to include more listings, for special games. We struggled to do so in the context of Computer for All. This is when a demanding reader walked in to ask us why we did not publish a special issue of the magazine that would be devoted to listings. We thought that this was a great idea and immediately started to plan to so as to have this special issue [the first issue of Pixel] by Christmas of 1983 (n.p).”

According to its editorial team, the publication of Pixel was founded on the acknowledgement of the dominance of software over hardware. This dominance was not clear during this early period in the Greek community of computer magazines, as the assumption was that advances in computer technology had mostly to do with hardware and its improvement, which made computers faster and more capable. Pixel’s pioneering sensitivity to the dynamics of the importance of software over hardware was rather novel in 1980s’ Greece.[3] For Manoussos (1983), software was the most difficult to obtain, a “ghost in the machine”. This expression echoes the perception of programming by its protagonists as being a “black art” (Ensmenger 2012) by “the high priests of a low cult.” (quoted in Computer 1980) It has been illustrated vividly on the cover of Time, April 1984, on which Bill Gates was showing off his skills under the headline: “Computer Software. The magic inside the machine” (Time 1984, April 16, 1). For Manoussos (Retrovisions of 80s 2019), at the time, “the thirst of home users for software was endless”. In his view, this explains the publishing of listings in the pages of home computing magazines. “The capability and the availability to write a few commands in BASIC (and, at times, in machine language), to run a program that supported some little application or a game,” he remembers, “was a defining feature of the so-called ‘heroic age of computing’.”

Manoussos further recalls that, back then, a new “home PC” (his expression) was introduced almost every month, which was frequently incompatible with the rest. This made the sharing of software between users of different machines rather impossible and resulted in increasing tension between users and providers of software for home computers. To be sure, in the international case, home computers were personal computers, but the term “personal computer” in the 1980s was used for the IBM PC and IBM-compatible PCs (Sumner and Gooday 2008; Sumner 2012). In the Greek case, however, the term “home PC’ was introduced so as to bridge the gap between home computers and PCs, by assuming that the most powerful home computers could also function as PCs. This was to happen by using home computers to run more PC-related (e.g. office-type) applications.[4] Listings to run such applications were, in the first years, also offered through Pixel, which helped to reduce the aforementioned tension.

Users of program listings were Greeks who wished to utilize their home computers but could not afford to purchase commercial software or wished to learn how to program them. Programming was understood as one of the essential aspects of the use of home computing. Pixel immediately became a vehicle for the dissemination of software in the form of program listings. From the first issue, the section of the magazine that included the program listings was entitled “Software” (Pixel 1984a; Pixel 1984b; Pixel 1984d; Pixel 1984e). Pixel was the first magazine on personal computers in Greece to dedicate a large part of its content to the publication of program listings. Indicatively, program listings occupied almost one-third of the total pages of the second issue. It was clear from the beginning that Pixel’s publication was response to the demand for new software by a growing number of amateur home computer users. According to the editorial team (Lekopoulos 1988a, 136):

“The aim of the magazine is to cover the lack of information available to the public on computers. The wider public does not really know what a computer is. Some have a hazy image in their minds, an image promoted by the general press. Even those who do have a better image, do not adequately understand how microcomputers will affect society. Pixel aims to cover the field of home computers (Oric, Spectrum, etc), closely observing the rapidly evolving market of microcomputers and occasionally intervening to shape it.”

Writing in Greek, i.e. using Greek fonts, frequently depended on the offering of program listings. Suggestively, the Greek importer of the Spectravideo home computer relied on Pixel for the dissemination of a program listing that allowed Greek users to have Greek fonts in this computer. This program was written in machine language by ELEAN Ltd, the official Greek importer of Spectravideo home computers. It was published in the third issue of Pixel (Pixel 1984b, 112).

The publication of listings established a strong interaction between Pixel and its readers. Many of them negotiated with the magazine the publication of their own software in the form of listings. Readers felt honored to have their software published and circulated through the pages of Pixel. Also, the publication of software through Pixel offered to its readers the opportunity to spot and report errors and to suggest possible corrections to published listings. As we learn from letters by readers, some of the program listings, which were copied from British and other international computer magazines, contained errors.[5] To many of Greek users, Pixel offered a forum to showcase their skills and programming expertise, to position themselves within the new socio-technical environment formed around the introduction and use of computers in the Greek society (Lekkas 2014b).

The foundation of Pixel was connected to the issue regarding the appropriate identity of a computer user. For its editorial team, a user had to be skilled in programming. In the absence of formalized education in computing, this user-programmer was to be trained through the magazine by participating in the collective production and use of program listings, and, further, by reading a series of special training articles and guides to programming languages of home microcomputers. These were, mainly, the versions of BASIC included in the package obtained during the purchase of a microcomputer. The emphasis on the importance of magazine-mediated training in programming declined by the end of the 1980s but never disappeared (Lekkas 2017). In the third issue, the editors communicated the magazine as “the ultimate expression of the dynamic field of home computers” (Zorzos 1984). It included a series of new columns, some of which went on for several years and gained substantial popularity. This was the case with the column Interferences (Επεμβάσεις), the first column in a Greek computer magazine to focus on modifications of microcomputer software, especially games (Tsouanas 1984, 16).

New columns on programming were also launched. Parallel Roads (Παράλληλοι Δρόμοι), offered a translation of a piece of software to all BASIC versions. This guaranteed compatibility between versions just as it offered an opportunity for practicing translation between versions, thereby making BASIC as a whole accessible to all users (Pixel 1984e, 36). In addition, this column sought to solve a problem that plagued the proper running of a home computer by its users. It had to do with the fact that a program for one home computer could not run to another even though in both cases the language used was BASIC. Variations in the BASIC dialects, as combined with differences between home computers, made incompatibility a great issue (Retrovisions of 80s 2019).

Through information offered by the Pixel column Parallel Roads, a reader could use the same program in several computers and, at the same time, “identify the changes in the commands of the various dialects so as to understand how to produce the compatibility that he needed.” (Pixel 1984d, 36). The proper use of the computer did not have to do with the simple keyboarding of commands but reached into changing these commands through programming. As for familiarity with BASIC, the magazine assumed that it was indispensable for the “first steps in the use of a home computer”. “We certainly know, all of us, how to write at least one program in BASIC, the most common language of home micros,” we read in a 1985 article in Pixel (Pixel 1985, 28).

“A rather risky endeavor”

The publisher of Pixel, Compupress Ltd, was founded in 1982, a year before the publication of Computer for All in January of 1983. In the 1980s, Compupress undertook several important initiatives in the field of publications of relevance to computing and related technologies and it was one of the first companies in Greece to publish specialty material on them. As explained through its website, “Compupress was founded in 1982 with the initial goal of publishing magazines and books in the field of Informatics and the then emergent ‘New Technology’” (Compupress 2019a). Compupress also published books and software for computers and home computers.[6] Computing technology magazines of the early 1980s were published by new and small publishing houses, or even computer stores, which also published books or produced software. Compupress is a good example of a new and relatively small publishing house of this period.

In the early 1980s, home computing was certainly not a topic dealt with by large publishing houses and computing professionals. It was mostly picked up by amateurs who saw in the field of microcomputer technology a potential for themselves (Lekkas 2014a). RAM, the first computer magazine by an established publishing house, the Lambrakis Press Group, did not appear before the late 1980s (February 1988). By contrast, as already mentioned, Compupress, the new and small publishing house that published Computer for All and Pixel, was launched six years earlier. To indicate the lasting contribution by amateurs, we can refer to a report by the first editor-in-chief of the computer magazine User, Giorgos Kouseras. User was launched in February of 1990 through the efforts of a few amateurs, from a small space in central Athens. Following in a tradition established in the 1980s, the magazine employed only a handful of employees, usually no more than two or three. They authored columns under pseudonyms so as to make it look as if the magazine employed more staff. According to Kouseras, this helped them to project an image of reliability and representativeness (Retromaniax 2019).

For Kouseras (Retromaniax 2019), the publication of computer magazines without the backing of an established publisher was “a rather risky endeavor”, with unpredictable financial repercussions. It was an endeavor for a “hobbyist, friendly, spontaneous and romantic era”. The publication of the first issues of User was always difficult, with the amateurs behind it being constantly on the verge of a financial disaster. This difficulty was shared by almost all early editors of computing magazines. According to Kouseras (Retromaniax 2019), publishing the first two years of the publication of User was especially hard. Each User issue was potentially the last one, as the magazine was struggling under financial burdens. Similarly, Manoussos recalls that the sales of the first issue, which appeared in Christmas of 1983, was “well below their expectations, especially considering the intensity of work required to prepare it.” This is why “the impression around Compupress was that the Pixel experiment was to die shortly” (Retrovisions of 80s 2019). It was proved that it did not.

The reliance on amateurs resulted in the establishment of relationships defined by friendship and comradeship within the members of the small group that published a computing magazine, as well as between this group and the readers of the magazine. It is within this context that photographs of the Pixel editors having fun at a tavern were published in the magazine on the occasion of the celebration of the five years of Compupress (Pixel 1988a, 12). The members of the editorial teams were usually very young. In an article published upon the completion of one year of publication of Computer for All, the editor wrote: “we have a very low average age. There are no ‘rigid structures’ in our company. We share a sense of friendship and a common passion to make each issue better than the previous one.” (Computer for All 1984, 10).

Following in the style of the cover chosen for the first issue (1983) of Pixel (Figure 1), all of the magazine covers were a faithful reproduction of the style of the cover of TIME magazine. TIME had actually dedicated its January 1982 issue to the importance of the computer games industry, introduced under the title Video Games Are Blitzing the World. Despite its beginning as an insert, Pixel magazine was so successful that it inspired its own child publications: the annual Super-Pixel (an annual guide), Pixel Junior, which focused on listings on home microcomputers once Pixel started to cover additional themes, and Pixelmania, which was devoted to gaming. Compupress also published the magazines Information and Compu Data, which were tailored to the more professional aspects of computer use. From January 1987, it added the publication of the GCS Newsletter, a publication of the Greek Computer Society (nowadays Ελληνική Εταιρεία Επιστημόνων και Επαγγελματιών Πληροφορικής και Επικοινωνιών – ΕΠΥ) (Pixel 1987a, 69).

The magazine regularly featured reviews of the Greek computer market, presenting the main computer stores and, later, the first software houses. Also, Pixel often featured interviews with business pioneers from these fields. It was one of the first Greek magazines to carry out comparative tests. They were published in Pixel throughout the 1980s.[7] One of the most successful initiatives was the creation of the Pixel Club in 1984. This club went a long way in solidifying the bond between the magazine and its readers. The creation of computer clubs ushered greatly in the creation of mediation nodes for the home microcomputer use during the 1980s (Lekkas and Tympas 2019).

Editors systematically sought information from abroad, especially when their own field of expertise was not yet developed in Greece. Information could be acquired through correspondence with international colleagues or Greek students who were paid to copy technical information from the international press. In 1985, a column entitled London calling (Εδώ Λονδίνο) was launched by the editor Vasilis Konstantinou. It aimed at bringing news to Greek users from the “metropolis of home computers”, as London was referred to due to being home to many home computer companies, including Sinclair, Amstrad, Acorn and others (Figure 2) (Lekopoulos 1988b, 35). Referring to London as a “metropolis” of home computing shows how close the Greek users were to the British computing scene. This was due to two reasons: First, the large community of Greeks who studied at British universities and naturally served as a bridge between this scene and Greek home computer users, and second, the importing of many British home computers to Greece (Lekkas, 2014a).

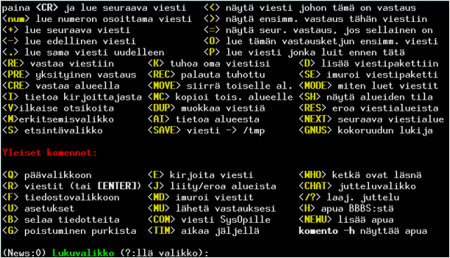

The column regularly informed Greek users about international shows and trade fairs, like the annual Personal Computers World Shows, which offered an opportunity for the most important manufacturers to exhibit their products (Konstantinou 1987). Konstantinou was one of the few editors of the magazine to have studied computer science. He actually did so in London, where he lived permanently. His reports to the column were transmitted electronically, probably a first in the Greek publishing world. The editor sent them through a FIDO bulletin board, a modem, which required a manual connection with a corresponding modem in the magazine, over a telephone line connecting Greece and the UK (Pixel 1987b, 17).

Also in 1985, Compupress had established an agreement with British publications in the field of computers and informatics for exclusive reprinting in its own publications (mainly Computer for All) of articles from the magazines Personal Computer World, Computing, Informatics and Datalink (Computer for All 1985, 94).

Pixel went through a similar revamping, starting with the November 1997 issue (134), published under the title Pixel NG (Next Generation). This was a magazine exclusively about gaming consoles. Pixel NG went out of circulation on October 1998, after 14 issues. The transformation of Pixel was in touch with similar transformations at the international level. In April 1988, the magazine’s editor introduced the changes in focus and content by stating: “Dear readers, as you have already noticed, going through the pages, the issue that you hold in your hands represents a very different image, which aims to help Pixel converge with the leading European magazines on informatics (Kyriakos 1988, 13).

Members of the Pixel community also contributed to the popularized of home computing through TV shows. In 1991, Compupress agreed with the Greek state television to produce three television series: One on personal computing (‘COMPUTERS: ΤΑ ΕΡΓΑΛΕΙΑ ΤΟΥ 2000’), one on gaming (‘THE COMPUTER SHOW’), and one on soccer game predictions and gambling. The Computer Show on ERT1, the main channel of the Greek state television, was hosted by Antonis Lekopoulos and Giorgos Kyparissis, both editors of Pixel (Compupress 2019b). Interestingly, Pixel organized concerts in stadiums, which included lotteries and entertainment activities. Through everything said so far, Pixel became the model for other Greek magazines in the field, which sought to copy its practices. For example, Market Guide, a special multiple pages column in Pixel that started with the March 1985 issue (8), was copied by other magazines, like Electronics and Computer (Ηλεκτρονική και Computer) (Ηλεκτρονική και Computer 1985) and RAM (RAM 1990).

The circulation of Pixel remained high during the entire 1980s. This seems even more impressive if we take into account that for many years the magazine only addressed users of home microcomputers and not of IBM compatibles, which represented a community much more prominent in other Western European countries. Pixel quickly obtained a readership in the order of tens of thousands and maintained it for years. According to data available from the Central Agency of Daily and Periodical Press S.A., the circulation of the 35th issue (July – August 1987) was about 25,000. This number did not include copies sold through subscriptions. According to the picture offered by Pixel itself, its average circulation for the period July 1986 to September 1987 was about 21,000 (Lekopoulos 1988a, 136). This accounted for 77.67% of the total sales of home microcomputer magazines – the main antagonists being MicroMad and EPTA (ΕΠΤΑ) (Lekopoulos 1988a, 137). At its peak, in 1987, the circulation of Pixel reached almost 30,000. This was higher than that of Computer for All, which had an average monthly circulation of 10,000-12,000 issues by targeting business users (Retrovisions of 80s 2019). In the early 1990s, according to the estimation of Kouseras, the Pixel circulation was about 20,000. Based on these numbers, we suggest that Pixel was the most successful Greek computing magazine of this era. Its circulation would only be matched by the computing magazine RAM during the next decade (Lekkas 2017).

“Hurray for Games!”

The focus on programming, as well as the publication of program listings, defined the run of Pixel throughout the 1980s. Its contents, however, gradually underwent noticeable transformation. Central to this transformation was the use of computers for entertainment, most notably for playing games. While programming itself was for some still a form of entertainment, there were many who thought of it as an unavoidable step to what was the real computing fun: games. By the mid-1980s, this step could actually be avoided because commercial computer games became available. This brought about a noticeable change, as knowledge of (and experience with tinkering with) the computer was no longer a key part of the culture of computing (Lekkas 2013; Lekkas 2014; Lekkas 2017).

A computer user could now be part of this culture by playing games on the computer without knowing anything else about it. The emphasis was shifting from programming the computer to using ready-made commercial programs for computer games. Playing games frequently meant competing against others, trying to get the highest score. Updates on the performance (scoring) in a whole range of games were regularly offered through computing magazines. Several of them, including Pixel Junior, ΖΖΑΠ!, SPRITE, GamePro, Computer Games and User, were almost exclusively covering the latest in computer games.

By 1987, Pixel begun to report important changes both in the technical characteristic and the aspects of use of home computers. These were due to the gradual dominance of affordable IBM compatibles,[8] but also the emergence of 16bit home microcomputers, which were superior when it came to audio and graphics. As such, it facilitated the creation and publication of impressive entertainment software. This oriented many to entertainment-related uses of the home computers. The emergence of Atari ST, Amiga 500 and other 16bit home computers marked an important turn for the Pixel content.[9] In comparison to the 8bit machines of the first half of the 1980s, they allowed for the production of “super graphics”, according to Pixel’s terminology. These super graphics impressed both the magazine’s editors and the users of home computers (Kyriakos 1987a, 9).

In September 1987, Pixel launched the first column dedicated exclusively to adventure games (Tsourinakis 1988, 30-34). Contrary to most other computer games, this category required more than fast reflexes and coordination from the user to implement an elaborate script. The genre was very popular among users of personal computers (Moss 2011). Entertainment software, and especially games with graphics, quickly gained in popularity. After 1988 they represented the dominant aspect of the use of home computers. It is suggestive that Super Pixel, the annual edition of Pixel, was published in 1988 under the title 1988: Hurray for Games! (1988: Ζήτω τα Games!) (Pixel 1988b, 161). In September 1989 (issue 58), Pixel changed its subtitle to Monthly Magazine on Home Micros and Computer Games. In the same year, the service Pixel Software Boutique was also introduced. It aimed at selling by mail computer game software for almost all kinds of home computers. The Pixel readers only had to select their preferred software and fill in the form provided (Figure 3) (Pixel 1989a, 77).

Starting with the 6th issue (1985), the pages dedicated to program listings had decreased, from one third to about 20% of the available space, while still remaining a substantial part of the magazine.[10] This reduction reflected the gradual availability of ready-made commercial software for home computers. Yet, innovative columns all but disappeared. The editors continue to value highly the use of home computers as a learning and programming tool. The constantly renewed the way they presented program listings so that “both expert and novice programmers can learn through them a few new techniques.” (Kyriakos 1987b, 10)

The unavailability of statistics on the use of 16bit home microcomputers for games makes it impossible to offer a safe estimate on the range of this use. However, the constant references to home microcomputers as ‘game machines’ (παιχνιδομηχανές) makes it clear that the use of home microcomputers for games was the dominant one, overshadowing the other types of uses. We should here take into account that home microcomputers of the second generation did not compare favorably to IBM-compatibles when it came to uses beyond gaming. Microcomputers were better only for electronic editing, and the use of graphics and sound.

Conclusion

Based on the research presented in this article, we can argue that the role of Pixel was catalytic in shaping the way users of home computers came to contact with and used this technology. Being relatively unknown to the vast majority of Greeks, and also being under constant reconfiguration, this technology was advanced only by satisfying the demand, apparent as early as in 1982, for media to connect it to users, to make it familiar to them, to instruct them how to do the necessary tinkering with this technology in order to adjust it to their own local needs. Computing magazines became this media, with Pixel being, as all evidence suggests, the most representative example. Home computing magazines, just like home computing itself, became mainstream, gradually, by the late 1980s, parallel to the emergence of entertainment uses as the dominant ones.

As we saw in the first section of this article, up to then, however, the role of Pixel in the diffusion of home computers in Greece had to do with three things: First, the shaping of a culture of use of home computers, connected to specific uses of this technology, like the programming and the production, entering and editing of program listings; second, the formation of groups around these uses, especially the one concerning the dissemination of computer software; and finally, third, the habituation of users to tinkering with home microcomputers as a way to adjust them to their preferred use. Pixel helped to promote all this through alternative channels, including TV and radio programs.

In the second section of this article, we argued that the publication of Pixel magazine reflected the need of an emerging community of users, who looked for ways to express their creativity and to pursuit a career in the new field of home computers. Given that this field was uncharted, this involved considerable risk and financial uncertainty. This kept the traditional actors in the business of publishing at a distance. The so-called “microcomputer revolution”, which is considered an important case of a “technological revolution”, fell, initially, to an important extent, upon the shoulders of amateur publishers (Retrovisions of 80s 2019).

In the third and final section we saw that the wider use of home computing technology came along the prevalence of their mainstream use, which had to do with the consumption of ready-made commercial software. We also saw that after 1987, on the grounds of the incorporation of devices for the reproduction of advanced graphics and sound, the 16bit version of home computers emerged as especially appropriate for the use of recreational software. The gradual emphasis on the recreational use, which challenged the view that tinkering with home computing was by itself pleasurable, lead to the ending of the publication of Pixel by the mid-1990s.

References

All links verified 16.6.2020

Research Material

‘Advertisement [Διαφήμιση].’ 1985. Computer for All, September.

‘Advertisement [Διαφήμιση].’ 1987a. Pixel, February.

‘Advertisement [Διαφήμιση].’ 1987c. Pixel, December, 182.

‘Advertisement [Διαφήμιση].’ 1988b. Pixel, April.

‘Advertisement [Διαφήμιση].’ 1988c. Pixel, June. 149.

‘Advertisement [Διαφήμιση].’ 1989b. Pixel, October.

‘Correspondence [Αλληλογραφία].” 1985b, Pixel, January.

‘Current Affairs [Στην Επικαιρότητα.]” 1990. RAM, February.

‘Events… Rumours… Comments… [Γεγονότα… Φήμες… Σχόλια…].’ 1987b. Pixel, November.

‘Events… Rumours… Comments…, 5 Years Compupress!!!! [Γεγονότα… Φήμες… Σχόλια…, 5 Years Compupress!!!!].’ 1988a. Pixel, March.

‘First Steps [Πρώτα Βήματα].’ 1985. Pixel, February.

‘Market Guide [Οδηγός Αγοράς].’ 1985. Ηλεκτρονική και Computer, December-January.

‘Parallel Roads [Παράλληλοι Δρόμοι]’. 1984c. Pixel, July-August.

‘Pixel Software Boutique.’ 1989a. Pixel, January.

‘Retail Prices Boards [Πίνακες Τιμών Λιανικής].’ 1990. RAM, February.

‘Software.’ 1984a. Pixel, May-June.

‘Software.’ 1984b. Pixel, July-August.

‘Software.’ 1984d. Pixel, September-October.

‘Software.’ 1984e. Pixel, November-December.

‘The Open Channel.’ 1980. Computer, March. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.1980.1653540.

‘YOU & US [ΕΣΕΙΣ & ΕΜΕΙΣ].’ 1986. MicroMad, February.

Websites

Compupress, ‘Company History [Ιστορικό Εταιρείας].’ Accessed September 7, 2019, http://www.compupress.gr/istoriko_gr.asp.

Compupress. ‘The Company. General information. [H Εταιρία. Γενικές Πληροφορίες]’ Accessed September 7, 2019, http://www.compupress.gr/taftotita_gr.asp.

Retromaniax. ‘Η ιστορία των πρώτων USER [The history of the first USER]’. Accessed September 7, 2019. https://retromaniax.gr/threads/%CE%97-%CE%B9%CF%83%CF%84%CE%BF%CF%81%CE%AF%CE%B1-%CF%84%CF%89%CE%BD-%CF%80%CF%81%CF%8E%CF%84%CF%89%CE%BD-user.3158/.

Retrovisions of 80s. ‘Ο Νικόλαος Μανούσος της Compupress στο retrovisions.gr.’ Accessed September 7, 2019. http://www.retrovisions.gr/joomla/index.php/reviews/2014-08-16-09-56-57/25-ceo-compupress-retrovisions-gr.

Literature

Brittain, James E. 1997. ‘The Evolution of Electrical and Electronics Engineering and the Proceedings of the IRE: 1938-1962.’ Proceedings of the IEEE 85 (5): 762–797.

Campbell-Kelly, Martin. 2003. From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Campbell-Kelly, Martin. 2007. ‘The History of the History of Software.’ IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 29 (4): 40–51.

Carver, Scott J. 1977. ‘”Tekhnologicheskii zhurnal”: An Early Russian Technoeconomic Periodical.’ Technology and Culture 18 (4): 622–643. https://doi.org/10.2307/3103589.

Ceruzzi, Paul E. 2003. A History of Modern Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Computer for All. 1984. January.

Corn, Joseph. 1992. ‘Educating the Enthusiast: Print and the Popularization of Technical Knowledge.’ in Possible Dreams: Enthusiasm for Technology in America, edited by John L. Wright, 19–33. Dearbon, Michigan: Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.

Dooley, Brendan Maurice. 1991. Science, Politics, and Society In Eighteenth-Century Italy: The Giornale de Letterati d’Italia and its World. New York: Garland.

Dritsa, Konstantina, Dimitris Mitropoulos, and Diomidis Spinellis. 2018. ‘Aspects of the History of Computing in Modern Greece.’ IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 40 (1): 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAHC.2018.012171267.

Ducklow, Hugh. 1973. ‘Science, Politics, and the ‘New Statesman’, 1930-1940.’ Synthesis: The Harvard University Journal in the History and Philosophy of Science, 1 (1): 27–30.

Ensmenger, Nathan. 2003. ‘Letting the ‘Computer Boys’ Take Over: Technology and the Politics of Organizational Transformation.’ International Review of Social History 48 (S11): 153–180. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859003001305

Ensmenger, Nathan. 2012. The Computer Boys Take Over: Computers, Programmers, and the Politics of Technical Expertise. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ferguson, Eugene. 1989. ‘Technical Journals and the History of Technology.’ In In Context: History and the History of Technology – Essays in Honor of Melvin Kranzberg, edited by Stephen H. Cutcliffe, 53–70. Pennsylvania: Lehigh University Press.

Gascoigne, Robert Mortimer. 1985. A Historical Catalogue of Scientific Oeriodicals, 1665–1900: With a Survey of Their Development. New York: Garland.

Gooday, Graeme, and James Sumner. 2008. ‘By Whose Standards? Standardization, Stability and Uniformity in the History of Information and Electrical Technologies.’ The British Journal for the History of Science 43 (3): 503–505. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007087410001196.

Guerreiro-Wilson, Robbie, Lars Heide, Matthias Kipping, Cecilia Pahlberg, Adrienne van den Bogaard, and Aristotle Tympas. 2004. ‘Information Systems and Technology in Organizations and Society: Review Essay.’ ‘Tensions of Europe’ Working Paper.

Hempstead, Colin A. 1995. ‘Representations of Transatlantic Telegraphy.’ Engineering Science & Education Journal 4 (6): 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1049/esej:19950616.

Hopwood, Nick. 1996. ‘Producing a Socialist Popular Science in the Weimar Republic.’ History Workshop Journal 41 (1): 117–153.

Houghton, Bernard. 1975. Scientific Periodicals : Their Historical Development, Characteristics, and Control. London: Bingley.

Kirkpatrick, Graeme. 2015. The Formation of Computer Gaming Culture. UK Gaming Magazines, 1981–1995. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Konstantinou, Vassilis. 1987. ‘PCW SHOW 1987.’ Pixel, November.

Kronick, David Abraham. 1976. A History of Scientific & Technical Periodicals: The Origins and Development of the Scientific and Technical Press, 1665-1790. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press.

Kyriakos, Christos. 1987a. ‘Pixel’s news [Τα Νέα του Pixel].’ Pixel, March.

Kyriakos, Christos. 1987b. ‘Pixel’s news [Τα Νέα του Pixel].’ Pixel, September.

Kyriakos, Christos. 1988. ‘Pixel’s news [Τα Νέα του Pixel].’ Pixel, July-August.

Lancashire Julie Ann. 1988. ‘An Historical Study of the Popularization of Science in General Science Periodicals in Britain, c.1890-c.1939.” PhD diss., University of Kent at Canterbury.

Lekkas, Theodore, and Aristotle Tympas. 2019. ‘”A club for all the Greeks”: Home Micro Computer Clubs between Magazines and Stores.’ Geschichte und Informatik / Histoire et Informatique 20: 103–125.

Lekkas, Theodore. 2013. ‘Software Piracy: Not Necessarily Evil, or its Role in the Software Development in Greece.’ In Knowledge Management and Intellectual Property, edited by Stathis Arapostathis, and Graham Dutfield, 85–106. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Lekkas, Theodore. 2014a. ‘Public Image and User Communities of the Home Computers in Greece, 1980–1990.’ PhD diss., National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Lekkas, Theodore. 2014b. ‘Legal Pirates Ltd: Home Computing Cultures in Early 1980s Greece.’ In Hacking Europe: From Computer Cultures to Demoscenes, edited by Gerard Alberts and Ruth Oldenziel, 73–103. New York: Springer.

Lekkas, Theodore. 2017. ‘Computer Technology Periodicals and the Circulation of Knowledge about the Personal Computer in 1980s Greece’. History of Technology 33 (1): 229–251. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474237260.0014.

Lekopoulos, Antonis, 1988a. ‘Pixel and HOME MICROS: Past, Present and Future [Pixel και HOME MICROS: Παρελθόν, Παρόν και Μέλλον].’ Pixel, February.

Lekopoulos, Antonis. 1988b. ‘Pixel Celebrates 50 issues [To Pixel γιορτάζει 50 τεύχη].’ Pixel, December.

Manoussos, Nikolaos. 1983. ‘A Letter from the Publisher [Γράμμα από τον Εκδότη].’ Pixel, November – December.

Moss, Richard. 2011. ‘A Truly Graphic Adventure: The 25-year Rise and Fall of a Beloved Genre.” Ars Technica, January 27, http://arstechnica.com/gaming/2011/01/history-of-graphic-adventures/.

Strange, P. 1985. ‘Two Electrical Periodicals: The Electrician and The Electrical Review 1880-1890’. IEE Proceedings A (Physical Science, Measurement and Instrumentation, Management and Education, Reviews) 132 (8): 574–581. https://doi.org/10.1049/ip-a-1:19850098.

Sumner, James. 2012. “’Today, Computers Should Interest Everybody’: The Meanings of Microcomputers.” Zeithistorische Forschungen 9 (2): 307–315. Accessed September 13, 2019. https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/site/40209294/default.aspx

Tsouanas, Nikos. 1984. ‘Break the Manic Miner’. Pixel, July – August.

Tsourinakis, Andreas, 1988. ‘Adventure [Περιπέτεια].’ Pixel, January.

Tsouroplis, Dimitris 1984. ‘Comparative Test. ORIC vs SPECTRUM [Συγκριτικό Τεστ. Oric εναντίον Spectrum].’ Pixel, May – June.

Tympas, Aristotle, Fotini Tsaglioti, and Theodore Lekkas. 2008. ‘Universal Machines vs. National Languages: Computerization as Production of New Localities.” In Proceedings of Technologies of Globalization, edited by R. Anderl, B. Arich-Gerz, and R. Schmiede, 223–234. Darmstadt: TU Darmstadt.

Tympas, Aristotle. 2003. ‘One Global Machine, Many Local Journals: The Proliferation of a Nation-specific Press in Electronic Computing in the Case of Greece.’ Paper presented at the Annual meeting for the Society for the History of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia, 16–19 October.

Yates, Joanne, and Craig Murphy. 2010. ‘By Whose Standards? Standardization, Stability and Uniformity in the History of Information and Electrical Technologies.’ The British Journal for the History of Science 43 (3): 503–505.

Zorzos, Grigoris. 1984. ‘Pixel’s news [Τα Νέα του Pixel].’ Pixel, July – August.

Notes

[1] Ferguson (1989) shows the importance of studying technology-related periodical publications. Strange (1985) offers a similar account for histories of journals. Brittain (1997) showcases the co-evolution of a journal and a technical discipline. Ducklow (1973), Carver (1977), Dooley (1991) and Hopwood (1996) offer a geographically, chronologically, and thematically disperse sample on the history of technical and scientific journals and periodicals or general journals and periodicals that were involved in science or technology issues. More specifically, Hopwood focuses on the magazine Urania, which had a circulation of approximately 25,000 copies between 1924 and 1933, when it was closed down by the Nazis. Houghton (1975), Kronick (1976) and Gasgoine (1985) have published more general accounts of the field. Lancashire (1988), Hempstead (1995) and Corn (1992) have studied periodicals like the ones discussed in this paper.

[2] Our interest in the history of the role of computer magazines goes back to the early 2000s (Tympas 2003).

[3] Lekkas (2014a) shows examples of the importance of software over hardware in 1980s Greece. Ceruzzi (2003), Campbell-Kelly (2003), Campbell-Kelly (2007) and Ensmenger (2012) have given us pioneering studies on the histories of software, which argue about the importance of software more generally.

[4] An indicative example is the listing of a logistics program (“Πρόγραμμα Αποθήκης”) for the Spectravideo home computer published in Pixel (1984, 109).

[5] In this example, the source of the copied listing was the Your Computer British computer magazine (Pixel 1985b, 117).

[6] For a sample of books, see Srully Blotnick, «To «χρυσό» βιβλίο των υπολογιστών σε μετάφραση» (“The golden” book of computers in translation”); Sp. Kalomitsini – Th. Papadimitriou, «Κομπιούτερς, απλά μαθήματα για όλους» (“Computer, simple lessons for everyone”); «AMSTRAD. Χίλιες και μια δυνατότητες» (“AMSTRAD. Thousands and one possibilities”), «ASSEMBLY ΓΙΑ ΤΟΥΣ ELECTRON & BBC» (“ASSEMBLY FOR ELECTRON & BBC”); all advertised in Pixel (1988c, 149). For samples of updates on software, see the following advertisements: the software ΠΡΟ-ΠΟ ‘HITPACK 13’ for the Amstrad 664/6128 in Pixel (1987c, 182); «H Γλώσσα Μηχανής του SPECTRUM» (“SPECTRUM machine language”) and «GRAPHICS ΚΑΙ ΚΙΝΗΣΗ ΣΤΟΝ SPECTRUM» (“Graphics and movement in SPECTRUM”) in Pixel (1988c, 149); Advertisement for the publication «WHO is WHO Πληροφορική» (“WHO is WHO Informatics”), in Pixel (1989b, 55).

[7] The first such test was published in the second issue of Pixel and compared the Spectrum and Oric home microcomputers (Tsouroplis 1984, 20–26).

[8] According to a research by Dataquest, in 1988 the number of PCs sold in Greece was 27,000 (RAM 1990, 20).

[9] Kirkpatrick (2015) offers a reflection of a culture of diverse practices in the early issues of UK gaming magazines.

[10] Pages 86-114 from a total of 124 pages of Pixel, issue 6 (1985).