game production, failures, oral history, business history

Tero Pasanen

Ph.D.

Digital Culture

University of Turku

Jaakko Suominen

jaasuo [a] utu.fi

Ph.D., Professor of Digital Culture

University of Turku

Tero Pasanen (1978–2022) in memoriam

How to cite: Pasanen, Tero & Jaakko Suominen. 2026. ”A Failed Attempt to Launch the Finnish Digital Game Industry: Amersoft 1984–1986”. WiderScreen Ajankohtaista. https://widerscreen.fi/numerot/ajankohtaista/a-failed-attempt-to-launch-the-finnish-digital-game-industry-br-amersoft-19841986/

Originally published in Finnish as Pasanen, Tero & Jaakko Suominen. 2018. ”Epäonnistunut yritys suomalaisen digitaalisen peliteollisuuden käynnistämiseksi: Amersoft 1984–1986.” Lähikuva 31 (4), 27–47. https://journal.fi/lahikuva/article/view/77932

Republished in English with a permission.

Between 1984 and 1986, Amersoft, a subsidiary of Amer Group, was the first ever Finnish company to attempt the large-scale publication of domestic computer games. However, despite high hopes, the business ultimately proved to be unprofitable and was shut down. In this article, we discuss the early stages of the Finnish digital game industry and the reasons behind Amersoft’s failure. Explaining that the reasons behind its collapse were related to the small size of Finland’s domestic gaming market, product quality issues, the import of foreign products, corporate strategy, the lack of intellectual capital, and software piracy.

Introduction

Amer Group, which began as a cigarette manufacturer and later expanded into a conglomerate of different business interests, made a brief excursion into computer game industry between 1984 and 1986. Amersoft, a subsidiary of the aforementioned Amer Group, was the first Finnish company to make a serious attempt at the large-scale publishing of domestic computer games. However, due to the small size of the Finnish market, the venture quickly proved to be unprofitable. In addition to publishing and translating computer-related literature and importing games and utility programs, Amersoft also managed to release several original games made by Finnish developers. The company also produced the first licensed Finnish computer games: a computer version of the Finnish board game Afrikan tähti (Star of Africa) and a game based on the 1986 film Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle (Uuno Turhapuro Moves to the Country), which became Amersoft’s final release as well as being the company’s most commercially successful game. In total, Amersoft released ten computer games, several utility programs, and over thirty computer-related books, some of which covered games and game programming.

The purpose of this article is to deepen the research into Finnish game history by examining the early, tentative steps of the now massive digital game industry. Juho Kuorikoski (2017, 118), who has written several popular works on the Finnish gaming and computer scene, refers to 1980s Finland’s gaming scene as the “Jurassic era of Finnish gaming.” In this context, the term “Jurassic” is not a reference to the geological era of dinosaurs but rather a popular term used by game reviewers to denote a bygone period, perceived as more primitive or at least different from our more modern games and game cultures. In our article, we ask why Amer Group entered the computer game industry in the first instance and why the Finnish digital game industry failed to take off in the 1980s, despite the rising popularity of gaming and computer hobbies. Due to its unique perspective, our article can be positioned within the field of technology studies related to business failures (see e.g., Paju 2009). Notably, in the history of information technology, failures have been less frequently addressed than success stories, though they provide excellent material for research.

Our theoretical framework builds on previous research into the digital game industry and history, as well as more general literature on cultural industry, particularly from the perspective of the interaction between local and global activities. As primary sources for the article, we use Amersoft’s game and book publications, advertisements in computer hobby magazines, Amer Group’s internal and customer magazines (especially AmerInfo), and interviews with former Amersoft employees (nine interviews in total). The interviewees were found using the snowball method: previously interviewed individuals suggested new interviewees. One interview was conducted face-to-face (a thematic interview with written notes, but no recording), while the others were conducted via email using a largely similar set of questions. The questions covered the person’s career at Amersoft, including inquiries about the company’s lifespan. The interviewees included individuals who worked in various roles at the company, from the CEO to editors, freelance writers, and programmers. More detailed information about the interviewees’ roles can be found in the references and bibliography.

The interviews compensate for the lack of primary source material. We were unfortunately unable to access the company’s archival material, which was lost in part due to various mergers and acquisitions over the years. Additionally, much of the material that the employees themselves possessed has also disappeared over the years. We will return to the problem surrounding source material in the final chapter, as it is a broader and more pressing issue in the study of the history of the digital game industry and other sectors. Unlike the company’s materials, Amersoft’s published games have not altogether disappeared.[1] However, we do not analyze the content of the games in detail, as our article focuses on the publisher rather than the games themselves.

The following study is thematically divided into three parts. The first section provides a concise overview of previous research and establishes the article’s theoretical framework. The second section is cultural-historical, outlining the operational environment in which Amersoft attempted to initiate professional Finnish game production in the mid-1980s. The final section focuses on the background of Amersoft’s founding, the launch of its digital game production as well as the challenges the company faced in bringing Finnish games to the domestic market. Finally, we outline some guidelines for future research.

Previous Research

We approach previous research from two perspectives: first, through literature addressing the gaming industry and its history; and second, by reviewing studies on cultural industries, creative economies, and economics, the models of which can be applied to our research case.

The historiography of the digital gaming industry has usually focused on the larger markets of the United States, Japan, and, to some extent, the U.K. These regions also represent the industry’s greatest success stories. However, even in these countries, critical historiographical research based on primary sources is still in its nascent stages. The current research and popular literature in the field include comprehensive general works (Haddon 1988; 2002; Herz 1997; Kent 2001; Dillon 2011; Herman 2016; Wade 2016; Consalvo 2016) as well as historiographies of individual hardware manufacturers (Sheff 1993; Bagnall 2011; Pettus 2013), publishers (Ryan 2011; Wilkins & Kean 2015; 2017), and game studios (Kushner 2003; 2012). The findings and conclusions of these works are not necessarily transferable to other markets, as gaming markets in different countries have unique characteristics tied to their culture and national regulations. Recent digital game historiography has emphasized the importance of accounting for national and local differences (Swalwell 2005; 2009; Saarikoski & Suominen 2009a; Pasanen 2011; Švelch 2013; 2018).

Research works examining the history of the gaming industry from a more nuanced, international perspective (see, for example, Donovan 2010; Zackariasson & Wilson 2012; Latorre 2013) have been even more challenging to find. One apparent reason for this is the geographical concentration of the global gaming industry, especially in the U.S. and Japan. These countries have operated on a global scale since the industry’s early days. Europe has not produced any major, successful hardware manufacturers, aside from a few microcomputer companies. Moreover, while there are many respected game studios in Europe, the number of major producers is limited. Notable examples include the French company Ubisoft, Swedish Paradox, and Austrian THQ Nordic.

In recent years, however, research has expanded. For example, the Nordic gaming industry has garnered increasing interest (see, for example, Sandqvist 2012; Jørgensen 2017; Jørgensen et al. 2017). However, a more detailed and critical examination of the early stages of the Nordic digital gaming industry still requires further research, which this article contributes to in this regard.

The history of the Finnish digital gaming industry has been studied relatively comprehensively, although, for example, the relationship between the digital gaming industry and other sectors, such as board games or gambling, remains virtually unexplored. Several researchers and authors have addressed the Finnish gaming industry—or more precisely, the gaming sector—from microcomputer hobbies (Saarikoski 2004; Saarikoski & Suominen 2009a) to its actual launch and subsequent development (Reunanen et al. 2013; Kuorikoski 2014; Lappalainen 2015). Game journalism, the subculture of computer enthusiasts producing demo programs, known as the demoscene (Reunanen 2017), and software piracy (Saarikoski & Suominen 2009b; Nikinmaa 2012) have also been topical subjects of study. In addition to games (Reunanen & Pärssinen 2014; Kultima & Peltokangas 2017), research and popular literature have covered the significance of individual hardware devices for the Finnish gaming industry and its surrounding culture (Kuorikoski 2017), mapping the success stories of the Finnish gaming industry (Niipola 2015). Various approaches to the historiography of games have also been explored (Suominen 2017).

Digital Games as Part of the Creative Economy

The gaming industry is a sector of the creative economy, though it is not often discussed within this framework (an early exception being Eskelinen 2005). More commonly, the gaming industry is presented as an arm of the software industry (e.g., Campbell-Kelly 2003). For its part, the creative economy refers to an economic system based on the production, exchange, and use of so-called creative products. In addition to games, examples of creative economy or business include advertising, architecture, film, software production, and research and development. Intangible rights, such as copyrights, patents, and trademarks, form the core of the creative economy (Howkins 2013, 5–6). The term cultural industry is also used in connection with the creative economy with the terms often used interchangeably (Galloway & Dunlop 2007, 17).

In the context of digital game culture, media and cultural convergence are often discussed in the literature (Jenkins 2006). The former term refers to the merging of different media forms both in content and technology, while the latter relates to the blurring of boundaries between producers and consumers. Henry Jenkins (ibid., 3) coined the term “participatory culture” to describe this process, as the consumer/user plays an active role in the development of media and its content. Modding, where players modify game code or graphic libraries (see, e.g., Sihvonen 2009; Sotamaa 2010), as well as streaming, where gaming events are broadcast live online (see, e.g., Hilvert-Bruce et al. 2018), are both examples of this cultural phenomenon.

Michael E. Porter’s (1990, 72) Diamond Model has been used to analyze the potential of individual companies in domestic markets as well as the competitive advantage of national markets in international markets. The Diamond Model consists of four interdependent factors. The first key area comprises production factors, i.e., the resources companies use to produce goods. These resources include skilled labor, capital, and infrastructure. The conditions of demand in the domestic market form the second factor, as they push companies to develop their products through various innovations. An informed customer base further drives this development. These innovation-based advances help companies compete in international markets. The third element in the framework of competitive advantage includes the industries related to and supporting financial activity. One example of supporting industries is geographical business clusters, where different companies enhance each other’s operations. The final factor consists of a company’s strategy, structure, and competition. Internal governance and culture are examples of this element. Therefore, competition again compels companies to continually develop their products.

Porter (1990) also notes two external factors that may affect a company’s competitiveness: chance and government administration. Chance refers to sudden variations in demand or rapidly spreading technological trends. Government administration, on the other hand, facilitates competition by creating national programs that benefit the industry.

The value chain refers to the actions and stages companies go through to bring their products to market (Porter 1998, 36–38). In this value creation process, each individual stage increases the value of the product. Zackariasson and Wilson (2012, 2–5) divide the gaming industry’s value chain into six components: 1) game developers (those responsible for content production); 2) publishers (those who finance and market game projects); 3) distribution (those responsible for distributing games to the market); 4) retailers (those who sell games); 5) customers (those who purchase games); and 6) consumers (those who play the games). Egenfeldt-Nielsen et al. (2013, 20) also identify six links in the value chain but place hardware manufacturers (companies producing game consoles and computer components) at the top of said chain. However, for their part, Egenfeldt-Nielsen et al. do not differentiate between customers and consumers. Thus, in this article, we consider Amersoft’s activities in relation to the aforementioned Diamond and value chain models.

From Arcade Games to Game Consoles and Home Computers

The origins of the digital gaming industry can be traced back to the early 1970s arcade games. Of course, games were already being created and manufactured for mainframe computers in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but these products were primarily technological experiments rather than commercial products. In less than five decades, digital games have emerged as one of the most dynamic sectors of the cultural industries, viewed both as an art form and pure entertainment (Mäyrä et al. 2010, 307; Kuorikoski 2018).

The development of the gaming industry has not, however, been a linear, deterministic march of technological progress. A significant example of this is apparent in the upheavals of the 1980s, a decade that witnessed the end of the golden age of arcade games, leading to a shift from public gaming spaces to private ones. In 1982, arcade games in the United States still generated around $8 billion in annual revenue, while the market share of console games was only half that, producing approximately $4 billion per annum (Rogers & Larsen 1984, 263). However, digital games were still viewed as products of relatively low social importance. Digital games were largely considered children’s media, holding minimal cultural value. While simulator games played on expensive machines attracted slightly older audiences, console gaming in particular was viewed as a child’s pastime. However, this lowly perception began to change in the 1990s (Suominen 2015, 85–90). Furthermore, game software did not yet enjoy copyright protection, while the gaming industry lacked a unified trade association.

The financial figures for the North American video game industry declined between 1983 and 1984. Affordable home computers attempted to fill the void left by consoles in the digital game market. Home computers were viewed as a more versatile alternative to consoles, which were limited to gaming (Gutman 1987). However, a decline in demand, coupled with an oversupply of different computer models, burst the market bubble of the home computer in the mid-1980s, leading many companies to bankruptcy (Haddon 2002, 55–56; Saarikoski 2004, 110). The US console game market nonetheless recovered within a few years following the 1985 release of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES).

The first independent game studios, such as Activision, which made games for Atari devices, were founded in the United States in the late 1970s. Before Activision, device manufacturers produced games exclusively for their own systems. At that time, in the beginning of the 1980s’ game development and publishing had not yet been established in either technological or business terms. In addition to companies focused solely on digital games, the second decade of the gaming industry saw many toy manufacturers, publishing companies, software producers, and manufacturers of computers and other consumer electronics trying their hand at the digital game market. The transition to digital games was also a natural progression for many crd and board game companies, Nintendo being a notable example. Additionally, several conglomerates experimented with the gaming industry in the 1980s and 1990s. For example, Japanese companies Vic Tokai and Toshiba EMI, whose parent companies, Tokai Corporation and Toshiba, were involved in industries ranging from natural resources to electronics, explored the gaming market. Major retailers also attempted to enter the gaming industry. For instance, the department store chain Sears released a series of Pong clones under the Tele-Games brand in the late 1970s. Large corporations and conglomerates that released individual games should be distinguished from those who did not seek long-term investment in the gaming industry. Those corporate projects primarily served the marketing purposes of their parent company or the conglomerate.[2] There was even interest in digital games behind the Iron Curtain. The East German projector manufacturer VEB Polyteknik developed and released the arcade game PolyPlay in 1985. PolyPlay included eight individual games and was the only arcade game ever produced in East Germany.

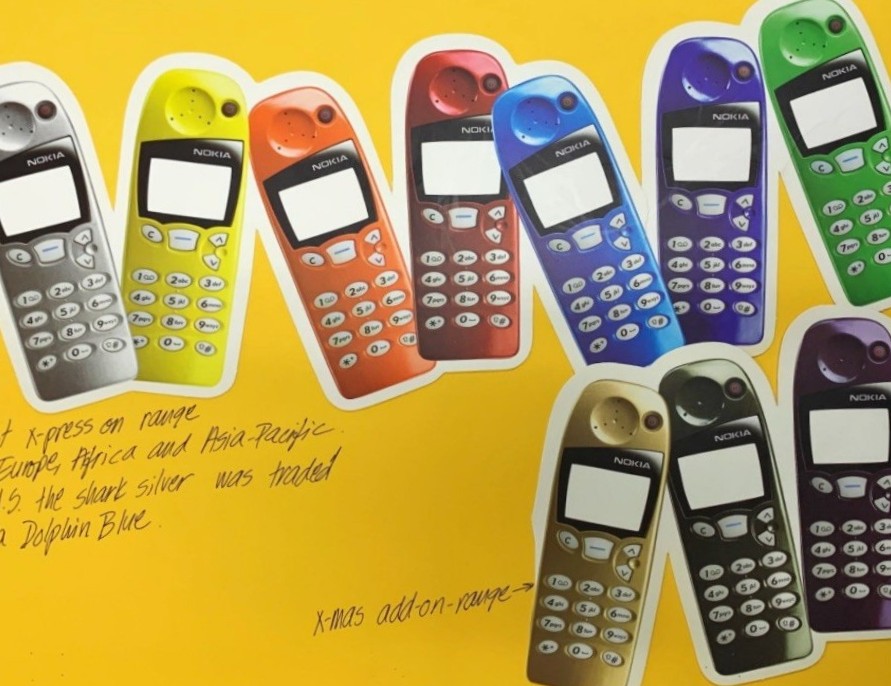

In the 1980s, the computer market had not yet consolidated around a few dominant players. Numerous device manufacturers competed for consumer attention, although most of them went bankrupt during the wave of closures in the latter part of the decade. Commodore was a dominant force during this period of early gaming-capable devices. The company’s most popular computer model was the Commodore 64 (C64), which sold an estimated 17–20 million units and had over 20,000 programs and games released for it (Dillon 2011, 82–83). While its competitors, such as the Sinclair ZX Spectrum, as well as computers using the MSX platform, managed to capture individual gaming markets, the C64 was the only home computer of its time to achieve global success. In Finland, this “computer of the republic” (MikroBitti 11/1985) sold an estimated 200,000 units (Kuorikoski 2017, 36), although exact sales figures are difficult to accurately calculate. The C64 cost around 3,000 Finnish marks in early 1985 (Printti 1/1985), but by the end of the year, its price had dropped to around 1,800 marks.[3] However, essential peripherals for gaming, such as mass storage drives, increased the total device cost: a cassette drive went for about 300 marks, while the popular 1541 disk drive was even more expensive than the main unit itself, costing approximately 2,300 marks (Printti 20/1985). By 1987, the C64 held an estimated two-thirds of the home computer market in Finland (Saarikoski 2004, 105). The machine’s success in Finland was largely due to the effective marketing by its importer, PCI-Data, and was further bolstered by successful localization efforts.[4] In this case, localization included highlighting national characteristics in advertising and producing Finnish-language manuals, literature, and magazine articles. The C64 played a significant role in the development of Finnish computer hobbies and the gaming industry, as it served as a training tool for future game developers (Kuorikoski 2017, 9, 39, 118).

The Emergence of Digital Game Cultures in Finland

Computer games and home microcomputing had a fundamental impact on the development of Finnish digital gaming culture in the early 1980s. Unlike in some other countries, a significant gaming culture did not emerge around arcade games in Finland, largely due to their limited import. Similarly, second-generation game consoles, the most famous being the Atari 2600, never archived wider commercial success (Saarikoski 2004, 217). These disappointing sales results were mainly because of the fact that consoles and other electronic games did not reach the Finnish gaming market before the North American gaming industry’s downturn (Saarikoski & Suominen 2009a, 22). Additionally, consoles were, for the most part, also relatively expensive, and their purchase was sometimes seen as more morally dubious than buying multipurpose home computers—despite the fact that home computers were often largely used for gaming.

The role of the gaming press in the birth of Finnish gaming culture cannot be underestimated. Computer magazines such as Printti (1984–1987), MikroBitti (1984–), and C=lehti (1987–1992) all played a crucial role in connecting game developers, importers, and players. These magazines had a substantial readership; MikroBitti, the most popular computer magazine of its time, had a circulation close to 40,000 throughout the 1980s (Saarikoski et al. 2017, 9). Digital games were rarely covered in mainstream media in the 1980s, therefore computer magazines were the only platform supporting the gaming hobby and the burgeoning culture developing around it. The game reviews and previews in these aforementioned magazines laid the foundation for Finnish game journalism, which was characterized by irony and humor (see Saarikoski & Suominen 2009b, 26–27). These reviews also directly impacted game sales (see Kuorikoski 2014, 18), as they were often the only source of information about new releases, the reviewers of which were often recruited from hobbyist circles.[5] In addition to spreading information, the magazines served as important publishing platforms for amateur-developed games, often distributed as code listings.

Raimo Suonio’s Chesmac, a chess game programmed for the Telmac 1800 computer[6] in 1979, is currently considered the earliest known Finnish commercial game release (Reunanen & Pärssinen 2014).[7] Although Finnish game hobbyists had also programmed games prior to that date, there would appear to be no known commercial distribution before the introduction of Chesmac. Finnish game publishing began more broadly in 1984 when Amersoft released a total of five games. The year 1985 was the most active year of the decade in terms of releases, as publishing activity quadrupled with the arrival of new players in the market.[8] Some of these new companies were importers of games, electronic entertainment, and computers, while others were brand names created by underage computer hobbyists. The following year witnessed the release of nine new games, three of which were updated versions of older games for the Commodore 64.[9] New publisher Triosoft, an importer of computer games and accessories, entered the market but ceased operations after releasing only three games. The most significant release of 1986 clearly was Sanxion, (Thalamus 1986) developed by Stavros Fasoulas, which was the first Finnish game to achieve international distribution.[10] Sanxion also proved to be a commercial success, earning its creator the title the “Paavo Nurmi of computer games” in the Finnish gaming press (MikroBitti 12/86, 72). Sanxion performed better internationally than domestically, becoming one of the most popular games of 1987 according to readers of the British computer game magazine Zzap!64 (25/1987, 74), reaching as high as seventh on the list in May of that year.[11] In Finland, however, its sales were only modest.[12]

In 1987, a few more Finnish game developers succeeded in finding international publishers for their games, thus sharing the fruits of Finnish game development with a wider audience. From a domestic gaming history perspective, the most notable release was Jukka Tapanimäki’s Octapolis (English Software 1987). Alongside Fasoulas, Tapanimäki was one of the most famous Finnish game developers of the decade. This trend continued in 1988. The following year, however, Finnish publishers were largely absent from the gaming scene, with only Avesoft and T&T-SOFT, which produced text-based games, releasing new titles.

The Videogames.fi wiki lists a total of 60 Finnish computer games released in the 1980s.[13] These releases were primarily produced by domestic game publishers and small hobbyist groups and only a small number of these games ever achieved international distribution.[14] The main gaming platforms included the VIC-20, Commodore 64, MSX, ZX Spectrum, and Commodore Amiga. In addition to commercial games, many non-commercial games were published as code listings in hobbyist computer magazines like MikroBitti and in the small electronic disk magazine Floppy Magazine. For example, there are at least 85 such games available for different versions of the Commodore platform.[15] The first Finnish advergames also appeared in the late 1980s, with Painterboy (1986) by Tikkurila as well as Hup-peli (1987) and Promille (1990) released by the Finnish Alcohol Monopoly’s educational division. For their part, the Finnish Medical Board and the Finnish Youth Education Association released Tupakistan 2200 (1987/1988) as part of an educational anti-smoking campaign.

Finnish game development in this era focused exclusively on home computers. It should be noted that not a single Finnish game was released for consoles in the 1980s, largely due to the high cost of licensing rights. Game designers in Finland were often individual hobbyists or small groups without the financial resources to purchase developer licenses or become full-time entrepreneurs. Further, many of these designers were also minors (Kuorikoski 2014, 9).

Amer’s Digital Leap into the Unknown: Launching Game Publishing

Amersoft was a subsidiary of Amer-yhtymä Oyj[16], a diversified company that was founded in 1950. In the 1980s, Amer’s business activities spanned tobacco products, car imports, sports equipment, clothing, and publishing and printing activities. The establishment of Amersoft in July 1984 was a result of a previous publishing agreement between the publishing company Weilin+Göös and PCI-Data, the importer of Commodore computers. This agreement concerned the publication of computer-related literature. At the same time, Weilin+Göös[17] ventured into the software business, leading to Amersoft’s founding as a separate entity. Amer aimed to capitalize on growing interest in information technology, both in the business world and consumer markets. However, its entry into game publishing was somewhat unconventional. To understand this move, it’s necessary to explore the background of the Weilin+Göös publishing company, which strongly influenced Amersoft’s formation.

Weilin+Göös, founded in 1872, was known for decades as a publisher of almanacs and calendars, holding the exclusive right from the University of Helsinki to publish almanacs. In the early 1960s, the company resumed book publishing to utilize its increased printing capacity. In the summer of 1970, the Bonsdorff family, which had controlled the company for 80 years, sold its majority stake to Amer-Tupakka Oy. This transaction suited both parties, allowing them to focus on their desired business endeavors. For example, Amer strengthened its publishing operations through this deal. By the early 1970s, Weilin+Göös’ publishing activities were divided into four departments, one of which focused on non-fiction and another on textbooks. The company experienced strong profits in the 1970s, particularly from the publication of large multi-volume works such as encyclopedias and illustrated books. However, the company’s fortunes later worsened, and the pressure to achieve quick financial success began to eventually affect the company’s operations. According to Allan Tiitta (1997, 76–78), who wrote the history of Weilin+Göös, “in the pursuit of rapid financial success, all sorts of experiments were tried, and there was impatience to wait for the results of one strategy before implementing another. This made the publishing policy inevitably erratic.” This impatience became evident in the early 1980s, especially in Amer’s experiments with information technology publishing.

In 1974, Weilin+Göös moved its headquarters from Mannerheimintie, the main thoroughfare of the Finnish capital Helsinki, to Espoo’s Tapiola district, into a new open-plan office designed by Bertel Ekengren (ibid., 80) as Amersoft employees later recalled (Rautakorpi, interview 2014; Litmanen, interview 2014). In 1982, the company was hit by the wider crisis in the book publishing industry, as the demand for books declined as competition intensified due to long-standing oversupply. Weilin+Göös began a rationalization program and sought out new partners. In the fall of 1983, it signed a collaboration agreement with PCI-Data/PET-Commodore, the importer of Commodore computers in Finland, which included popular models like the VIC-20 and Commodore 64. Amer then rebranded its book publishing and printing operations as the “communications industry,” reflecting the growing shift toward information technology and the emerging information society. In June 1984, Amersoft was established within the industry to continue the company’s previous computer-related publishing activities.[18] In addition to books, Amersoft also sold software and secured exclusive distribution rights with companies such as the world’s then-largest microcomputer software producer, U.S.-based Micro-Pro International, known for its WordStar word processing software (Tiitta 1997, 110–111; AmerInfo 4/1984; AmerInfo 3/1986). In 1986, Amersoft also signed an exclusive agreement with Digital Research, which produced the graphical GEM interface for PC computers and related applications (AmerInfo 3/1986).

So, why did Amer enter the IT sector in the first place? At first glance, the company’s leap into the gaming industry seems like an unusual business move, but its motivation was likely the same as that of many diversified companies of the time. In the early 1980s, information technology was a rapidly growing phenomenon that represented enormous business potential. Computers, which had previously been used almost exclusively in educational and professional settings, were now entering people’s homes and daily lives through the advent of personal computers. The role of software in selling personal computers and spreading computer hobbies was crucial, while successful marketing also played a part in their popularity (Saarikoski 2004, 98). For the average home user, games were the most familiar example of computer software. Amersoft’s business was divided into three sectors: 1) publishing computer-related literature, 2) importing and publishing professional software, and 3) consumer products, including games and utility software (Lautsi, interview 2014), which aimed to cover a wide range of software-related activities.[19] With this, the business model appeared diverse and promising in a growing market.

During its operation, Amersoft published 32 books and nine software titles but only 13 Finnish games. In 1984, the company released games such as Mehulinja (Juice Line), Herkkusuu (Sweet Tooth), Myyräjahti (Mole Hunt), and Raharuhtinas (King of Money), all programmed by Simo Ojaniemi. Three of these games were for the Commodore VIC-20, while Raharuhtinas was the first commercially released Finnish game for the Commodore 64. That same year, Juha and Mika Salomäki’s Yleisurheilu (Track and Field) was also published.

The year 1985 was Amersoft’s most active in terms of releases, with games such as Janne Julkunen and Juha Granberg’s 10… Knock Out!, Jyri Lehtonen’s Crash 16 and Delta 16, Pekka Pesonen’s Halley’s Comet, Risto Lankinen’s Tsapp! 16 (Zap! 16) and Tsapp! (Zap!), and Otso Pakarinen and Jari Heikkinen’s licensed game Afrikan Tähti (Star of Africa). The following year, Amersoft published only one more game, the earlier-mentioned Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle (Uuno Turhapuro Moves to the Country), programmed by Pasi Hytönen (see MikroBitti 4/1987, 36–38). This game became the company’s most commercially successful release, selling around 2,000 copies according to software supplier Petter Kinnunen (interview 2014). However, these sales figures should be approached with caution, as the game never appeared on any sales charts maintained by computer magazines, which it should have, given the reported sales numbers.

It’s unsurprising that Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle became Amersoft’s most famous and popular game, as the Uuno Turhapuro films were extremely popular in Finland. According to media researcher Jukka Sihvonen (1991, 13), Uuno’s character and films skillfully reflected and filtered a variety of Finland’s cultural and social elements. Veijo Hietala (2015, 99) explained Uuno’s enduring popularity by noting that “the character has found a receptive resonance in the collective consciousness of its audience.” Sihvonen (1991, 19) also emphasized Uuno’s performativity, not only his verbal activity but also his ability for physical comedy. It could be argued that Uuno, a well-known character with exaggerated capabilities, was an ideal protagonist for a video game.

Other Amersoft games sold an estimated 50–100 copies each (Kinnunen, interview 2014). The company also imported foreign games for the MSX platform (see MikroBitti 8/1985; 10/1985).[20] However, book publishing was much more profitable for Amersoft than game publishing. Some works, such as Kaikki Kuusnelosesta: Commodore 64 (All about the Sixty-four: Commodore 64) (Onosko 1983), went through multiple reprints (Nyström, interview 2014), and approximately 15,000 copies of this book were eventually sold (Lautsi, interview 2014). Initially, the published books were translations, but later works by Finnish authors, such as Osmo A. Wiio (1985) and Risto Linturi (1985), were published, too.[21] Despite its publishing activities, Amersoft’s overall business incurred significant losses. For example, in 1986, with a revenue of about three million Finnish marks, the company recorded an estimated loss of two million marks (Rautakorpi, interview 2014).

End of Experiment: The Termination of Game Publishing

In addition to widespread piracy, the primary reason why a viable game industry never emerged in Finland during the 1980s was the country’s relatively small domestic market. By the mid-decade, game sales amounted to tens of millions of Finnish marks (Kuorikoski 2017, 81–82), while domestic game sales were minimal. Sweden also suffered from a small market, however, Swedish game developers moved abroad to places like England, where game development could be done professionally (Sandqvist 2012). However, few from Finland followed suit. Perhaps the most enduring legacy of Finland’s 1980s gaming experiments are the “Finnish heroic stories of game programming” (Saarikoski 2004, 263–274). The most famous of these “mythical hero coders” are Stavros Fasoulas, Jukka Tapanimäki, and Pasi Hytönen (Kuorikoski 2017, 128).

Amersoft was the first Finnish company to take aim at the domestic game market, but it still failed in this endeavor. Porter’s (1990) Diamond model, introduced earlier, helps illustrate the challenging environment in which Amersoft attempted to launch its game publishing business. It highlights the factors needed for a successful business, whether in domestic or international markets. The following analysis provides reasons for the end of this experimental business by the end of 1986.

Amersoft was not entirely lacking in key production factors, but these determinants were insufficient. In the mid-1980s, game development did not require vast financial resources. These relatively home-grown projects were backed by individual coders or small groups, with payments ranging from a few hundred to thousands of marks (Pärssinen & Reunanen 2015). Towards the end of its business, Amersoft’s payouts increased. Simo Ojaniemi’s first games received a one-time payment of 1,000–2,000 marks per game (Kuorikoski 2017, 123). For Delta 16, Amersoft paid a 3,000-mark advance and a 15% cut of each copy sold.[22] For Afrikan tähti (Star of Africa), a one-time payment of 10,000 marks was made, which was shared among its creators (Saarikoski 2004, 265; Pakarinen, interview 2014).[23] However, game publishing never became Amersoft’s main source of income. The disparity between book, software, and game publishing also affected the allocation of the company’s financial resources. For example, advertising in computer magazines focused more on literature and utility software than on games, with the exception of Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle (Uuno Turhapuro Moves to the Countryside), which received significantly more marketing attention, although its pre-release marketing collapsed due to production issues (Kinnunen, interview 2014).[24] This investment also likely contributed to the game’s sales figures.

High-quality intangible assets are essential for companies in the creative economy. In the 1980s, domestic games did not yet possess such capital. Amersoft sought to compensate for this apparent lack of capital through licensed games (Kinnunen, interview 2014). The value of trademarks like Afrikan tähti and Uuno Turhapuro had already been proven in the entertainment market. Many foreign games sold in Finland were also based on well-known pop culture brands.[25] However, there were challenges in leveraging trademarks. Amersoft easily acquired the rights to use the movie Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle from Nasse Setä Oy company, but the copyright organization Teosto allowed the original theme music to be used for only one minute (Kinnunen, interview 2014) and these 60 seconds were used in the game’s intro.

Another critical production factor is skilled labor. Because Amersoft’s employees had no previous experience in game publishing or production, this deficiency likely impacted costs and managing contacts. Game development at Amersoft was characterized by a general level of amateurishness. There were no independent game studios in Finland yet; the first were only established in the following decade. Finnish game developers approached game design from a technical innovation and gameplay perspective, rather than focusing on graphics or content (Kuorikoski 2015, 9). Game projects were marked by a desire to experiment and test one’s own skills (Kuorikoski 2014, 12). This approach wasn’t always the most commercially successful or consumer friendly. However, this design philosophy did not significantly influence the projects Amersoft initiated itself. Further, Amersoft had no in-house programmers (Nyström, interview 2014); the company found game developers through programming competitions and computer clubs. Individual programmers also approached the company with their game demos, and Amersoft was offered numerous games and software, reportedly up to dozens per month at its peak (Kuorikoski 2014, 16). However, Amersoft’s collaborations with individual game developers typically lasted for only one project, so the skills and collaboration between the game developer and Amersoft did not have time to mature into a lasting professional relationship.

Based on hardware penetration, there was likely demand for Finnish computer games in the domestic market during the 1980s. However, the Finnish game market was based exclusively on the sale and import of foreign games. The excellent sales figures of the “Computer of the Republic,” the Commodore 64, never correlated with the sales of Finnish games. Domestic games sold in the tens or hundreds per title, with only a few exceptions (Kuorikoski 2014, 16–17). A game’s Finnish origin was not a selling point, even though gaming magazines of the time emphasized the Finnish character of the releases. In reviews, Finnishness nonetheless earned games “extra points” and often ensured somewhat gentler criticism.

Company culture does not develop overnight; it takes time to form. This was also true for the Finnish game industry. The amateurishness and certain lack of vision in the 1980s can be viewed as a necessary growth phase that companies had to endure before the actual birth of the Finnish game industry in the mid-1990s. Finland’s lack of professional publishers and game studios meant that industry clusters did not form. Amersoft had affiliated companies that handled domestic distribution and the retailing of games. Some of these affiliations were formed as a result of Amer Group’s corporate acquisitions. One glaring issue was the low visibility of Amersoft’s games in the gaming press.[26] The company’s games were rarely mentioned in magazines, which is odd considering that Amersoft employees even wrote game reviews for these publications.[27] Instead, Amersoft’s translated literature received more column space in the form of ads and articles (see, for example, MikroBitti 2/1985; 11/1985). The published articles not only reviewed Amersoft’s books but also publications from other publishers.

Amersoft primarily targeted the domestic game market, however, it never consistently sought to export its products abroad after its publishing activities began, for example, through collaboration with Toptronics or foreign partners. The primary reason for this was likely the decision to release exclusively Finnish-language games. The small selection of games also suffered from a lack of intangible capital. The company had plans to sell Afrikan tähti and Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle abroad, but these plans did not materialize before Amersoft’s game division was sold (Kinnunen, interview 2014). These games would naturally have been localized into English as well. Although the export of games never came to fruition, the attempt was quite forward-thinking, as internationalization only became seen as a necessity for success in the mid-1990s (Kuorikoski 2015, 17). However, it is doubtful whether the company ever had the capacity to export games. Amersoft lacked a detailed and determined strategy for game publishing, which manifested as a general lack of direction. The company was simply an experiment by Amer Group in an attempt to tap into the growing computer business. Further, the rationale behind this experiment was even questioned within the company:

“Amersoft was a wild leap into the unknown by Amer… Even then – although I was young and inexperienced – I wondered what sense it made for Amer to get involved in such an endeavor, as it had no substance related to the field. Now, nearly 30 years wiser, it seems even crazier!” (Rautakorpi, interview 2014).

Amersoft’s organizational structure was quite traditional. The CEO, Gunnar Nyström, oversaw the departments responsible for different business areas. The staff also included an editor, a sales representative, and a sales manager.[28] Further personnel resources were allocated to the import and publishing of professional software. Consumer products, including games and other utility software, were managed in turn by Petteri Bergius, Petter Kinnunen, Jouko Riikonen, and Jukka Rydenfeldt (Petteri Bergius, Lautsi, Kinnunen, Pakarinen, interviews 2014). Based on the research material, it is impossible to accurately assess the flexibility of Amersoft’s corporate structure. Generally, Amer Group had a business culture based on precise financial calculations (Tiitta 1997, 77). However, it can be assumed that Amersoft’s operating environment was quite free and adaptable (Litmanen, interview 2014), which was guided by a relatively small staff running an experimental business within the creative industry, collaborating with computer enthusiasts, some of whom were still minors.

The import of foreign games likely did not prevent the birth of the domestic game industry, although it certainly had an impact on the sales of Finnish games. Amersoft also explored game importing, but there were strong competitors in that field, such as Toptronics[29] and Sanura-Suomi. It is unurprising that the views of game publishers and importers differ regarding the significance of foreign games. Risto Lankinen, who worked at Amersoft, cites piracy and game imports as the primary reasons for Amersoft’s downfall. This perspective is interesting because Amersoft itself was involved in importing during its early stages. On the other hand, Petri Lehmuskoski, founder of Toptronics, emphasizes the small market, lack of marketing, and the generally poor quality of Finnish games for the slow growth of the domestic game industry (Kuorikoski 2014, 16–17).[30] Petteri Bergius, a software supplier for Amersoft, believes that losses from professional software were the final blow to the company’s operations (Kuorikoski 2017, 124).

The quality issue was partly influenced by the company’s aforementioned innovation-driven game design philosophy. To be commercially successful, the games required more than simply a developer’s desire to experiment. None of Amersoft’s published games stood out in terms of quality compared to other competing imported products of the time, despite Amersoft’s attempts to publish various types of games: sports games, a space game, an adventure game, action games, and so on.[31] Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle was quite polished in appearance, but its notoriously high difficulty level affected its playability. There were many games available that were of better quality and/or marketed more effectively. Software piracy (see Saarikoski & Suominen 2009a; Nikinmaa 2012), which plagued Finnish and international game markets alike in the 1980s,[32] also contributed to the poor sales of domestic games. Cassettes and disks, which were the formats for the C64, were very easy to copy. There were also a slew of programs available for this purpose, and Amersoft’s games did not use even basic copy protection like printed manuals but, according to Petter Kinnunen (interview 2014), relied on sound levels instead. However, this has not been confirmed by other sources. Copied games could also spread among computer enthusiasts more rapidly than they could be brought to market by importers. As piracy was not yet illegal in the early 1980s in Finland,[33] game developers thus tried to make piracy a moral issue through the game press (Saarikoski & Suominen 2009a, 23–24). Ironically, the game press itself had inadvertently created the piracy problem in the early years of the decade (Nikinmaa 2012, 15–16).

External factors such as chance and government funding were not significant players during the “Jurassic era” of the Finnish game industry. Amersoft was the first and only notable Finnish publisher of its time attempting to initiate domestic computer game production. Random or unexpected coincidences did not save the company from the problems faced by gaming pioneers. There were also no national programs initiated by Finnish public institutions in the 1980s to develop game production.[34] The reason for this was the low societal status of games and the general amateurism of the field. The Finnish information society project, of which the game industry is considered a part, only really began in the mid-1990s when Esko Aho’s government published the first strategic report on the subject. Founded in 1983, Tekes—now Business Finland—only began funding the Finnish game industry in the late 1990s. [35] The agency’s eventual funding has had a tremendous impact on the development of the Finnish game industry. Likewise, many other efforts to internationalize sectors of cultural industries only began after the 1980s.

The reasons for Amersoft’s business collapse were fairly obvious: it failed to provide tangible added value to its parent company. Initially, the Amer Group offered its subsidiary more freedom to engage in business based on the sale of “entertainment and game software” (MikroBitti 3/1984, 24). However, daily operations focused more on book publishing. Eventually, the parent company shut the experimental project down because Amersoft never delivered the desired results. Amersoft’s games generally sold very poorly. In addition to external factors, the primary reasons for this were the lack of intellectual capital, a small and inconsistent product profile, and minimal marketing. Low demand only emphasized the problems in Amersoft’s value chain, which centered on professional game creation and production, in particular. The game publishing lacked a clear strategy or direction that would have been necessary for a breakthrough in the small domestic market. However, it is worth pondering whether Amer closed its subsidiary’s operations too early. At the time of its closure, the quality development of Amersoft’s products was clearly moving on an upward trajectory, thanks to licensed games. The high-quality production of planned games, such as the rumored Uuno Turhapuro sequel (Kinnunen, interview 2014; Pärssinen 2014; Kuorikoski 2014, 16), could have even opened doors to international markets. However, the parent company viewed the game side as a failed experiment and did not consider the publication of computer literature important enough to require a separate subsidiary.

Amersoft’s era was brief and turbulent amidst Amer’s and Weilin+Göös’s other challenges. The publisher, for instance, lost a bidding competition related to the financially valuable rights to exclusively publish almanacs, causing internal issues within the company. The old management was soon replaced by a new one, and Amer sold Amersoft’s software business to Tietoväylä in December 1986. According to a news article published by Amer-Info about the sale, Amersoft’s turnover in 1986 was 3 million Finnish marks, half of which came from books. Tietoväylä’s turnover that same year was 48 million. Of Amersoft’s eight employees at the time, four transferred to Tietoväylä, and four remained with the Amer Group (Amer-Info 1/1987). However, Tietoväylä did not continue publishing games but focused rather on office software, for which it was specifically known (Kinnunen, interview 2014). Computer book publishing returned to Weilin+Göös in January 1987 (Tiitta 1997, 134), but the company had no interest in publishing literature related to the field (Heli Bergius, interview 2014).

Guidelines for Future Research

Our article provides an overview of the capabilities and conditions under which Amersoft attempted to launch the Finnish game industry. It highlights the business factors and their direct impact on the failure of Amer Group’s game experiment, placing this within the broader context of Finnish game cultures and industry. These factors can be summarized as the small size of the domestic game market, the lack of a consistent corporate strategy, widespread software piracy, the import of foreign games, the lack of intellectual capital, and the generally low quality of the published games. However, it might be incorrect to speak only of its failure, as Amersoft succeeded in publishing a total of 13 computer games. Nevertheless, the ultimate measure of business is its profitability, and, in this respect, Amersoft did not succeed. It is also important to remember that the company’s downfall was not solely due to its gaming operations but also the unprofitability of other business sectors within the company.

Our article also illustrates the challenges of archival research when analyzing pioneering companies like Amersoft. The company’s lifespan was short, and its business was sold off in parts to various entities. Notably, in the 1980s, little importance was attached to the pioneering work of the Finnish game industry, and, thus, the materials left behind by the company were naturally deemed worthless. No archival material on Amersoft was found, even in the Central Archives for Finnish Business Records (ELKA). Few people could have predicted in the 1980s that the industry would one day grow into a billion-dollar business. As no archival material has been found, we have emphasized interviews in this article, which are based on the memories of former employees from three decades ago. As a result, it is impossible to accurately verify certain claims, observations, and findings. Unfortunately, the written materials preserved by interviewees from the time have also been lost over the years. In addition to interviews, we have used research materials such as Amer’s internal and customer magazines, published computer-related news, reviews, and product advertisements concerning Amersoft and its products. We have also examined the available products published by Amersoft as well as documents and interviews published online and in literature. The digitization of computer magazines, along with enthusiast-maintained websites and databases, are crucial for research of this nature. In the future, greater care must be taken to ensure that archival materials are better preserved and accessible for research, especially in rising industries like digital gaming. Companies should bear in mind that archival material can also be used to improve their operations.

Our article contributes new insights into the early stages of the national digital game industry within the framework of cultural industry and computer history. The perspective on the early history of the Finnish game industry can be expanded in many directions from here. The early stages of the 1980s alone require more in-depth research, including further investigation into other game publishers and companies such as Triosoft and T&T-Soft. The production of games by the Finnish Slot Machine Association (RAY) and other non-digital games, such as board games from the late 19th century to the present (see, e.g., Ylänen 2017), also require further research. In addition to case studies, there is an express need to examine broader frameworks. Two potential cases are the history of the Finnish game industry as part of the larger media industry or the internationalization of Finnish game companies. This internationalization could also be compared to similar projects in other creative fields or cultural industries, such as the internationalization of design, popular music, film, television production, and literature.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Research Council of Finland-funded Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies project (312396). We also extend our thanks to Petri Saarikoski, Markku Reunanen, and the editors and reviewers of Lähikuva for their valuable comments on the manuscript. This article was originally published in Finnish as Pasanen, Tero & Jaakko Suominen. 2018. ”Epäonnistunut yritys suomalaisen digitaalisen peliteollisuuden käynnistämiseksi: Amersoft 1984–1986.” Lähikuva 31 (4), 27–47. https://journal.fi/lahikuva/article/view/77932

Sources

All links verified 21.1.2026.

Interviews (interviewer Jaakko Suominen)

Bergius, Heli. Amersoft. Kustannustoimittaja (Editor). Email interview 14 May 2014.

Bergius, Petteri. Amersoft. Ohjelmistotoimittaja (Software Supplier). Email interview 23 April 2014.

Kinnunen, Petter. Amersoft. Ohjelmistotoimittaja (Software Supplier). Interview 8 March 2014. Coffee House Keskustori, Tampere, Finland.

Nyström, Gunnar. Amersoft. Toimitusjohtaja (CEO). Email interview 15 May 2014.

Lautsi, Tapio. Amersoft. Myyntipäällikkö (Sales Manager). Email interview 22 April 2014.

Litmanen, Sirpa. Amersoft. Kustannustoimittaja (Editor). Email interview 20 June 2014.

Pakarinen, Otso. Freelance-ohjelmoija (Freelance Programmer). Email interview 11 March 2014.

Rautakorpi, Risto. Amersoft. Ohjelmistopäällikkö (Software Manager). Email interview 17 April 2014.

Ruohonen, Mikko. Freelance-tietokirjoittaja (Freelance Nonfiction Writer). Email interview 5 September 2018.

Magazines and other publications

AmerInfo 1984–1987.

MikroBitti 1984–1987.

Poke & Peek! 1983–1984.

Printti 1984–1987.

Tietokone 4/1984.

Zzap!64 1987.

Online sources

Hiltunen, Koopee & Suvi Latva. 2013. Peliteollisuus – kehityspolku. Helsinki: Tekes. Viitattu 21.8.2018. http://www.neogames.fi/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Tekes_Peliteollisuus_kehityspolku_2013.pdf [Link no longer active].

Pärssinen, Manu. 2014. ”Näin syntyi Uuno Turhapuro -peli”. V2.fi 13.2.2014. Viitattu 6.9.2018. https://www.v2.fi/artikkelit/pelit/1404/Nain-syntyi-Uuno-Turhapuro-peli/.

Pärssinen, Manu & Markku Reunanen. 2015. ”Näin käynnistyi Suomen peliteollisuus: Haastattelussa Simo Ojaniemi”. V2.fi 19.8.2015. Viitattu 23.8.2018. https://www.v2.fi/artikkelit/ pelit/1738/Nain-kaynnistyi-Suomen-peliteollisuus/ [Link no longer active].

Neogames. 2015. Tekes – 10 years of funding and networks for the Finnish game industry. Viitattu 13.8.2018. http://http://www.neogames.fi/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/TEKES-SKENE_Info_ Graafit_99x140_12-08.pdf [Link no longer active].

Suomen Commodore-arkisto. Viitattu 9.8.2018. http://www.ntrautanen.fi/computers/commodore/arkisto.htm [Link no longer active].

Videogames.fi. Viitattu 9.8.2018. http://www.videogames.fi

Literature

Bagnall, Brian. 2011. Commodore 64: A Company on the Edge. Variant Press.

Campbell-Kelly, Martin. 2003. From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Consalvo, Mia. 2016. Atari to Zelda: Japan’s Video Games in Global Context. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dillon, Roberto. 2011. The Golden Age of Video Games: The Birth of a Multibillion Dollar Industry. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Donovan, Tristan. 2010. Replay: The History of Video Games. Lewes: Yellow Ant.

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon, Jonas Heide Smith & Susana Pajares Tosca. 2013. Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Eskelinen, Markku. 2005. Pelit ja pelitutkimus luovassa taloudessa. Helsinki: Sitra.

Galloway, Susan & Stewart Dunlop. 2007. “Critique of Definitions of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Public Policy.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 13 (1), 17–31.

Gutman, Dan. 1987. “The Fall and Rise of Computer Games.” COMPUTE!’s Apple Applications 5 (2), 64–65.

Haddon, Leslie. 1988. “Electronic and Computer Games: The History of an Interactive Medium.” Screen 29 (2), 52–73.

Haddon, Leslie. 2002. “Elektronisten pelien oppivuodet.” In Erkki Huhtamo & Sonja Kangas (eds.) Mariosofia: Elektronisten pelien kulttuuri, 47–69. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Herman, Leonard. 2016. Phoenix IV: The History of the Videogame Industry. Springfield: Rolenta Press.

Herz, J. C. 1997. Joystick Nation: How Videogames Ate Our Quarters, Won Our Hearts, and Rewired Our Minds. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Hietala, Veijo. 2015. “Uuno Turhapuro suomalaisen kulttuurin terapeuttina.” In Seppo Knuuttila, Pekka Hakamies & Elina Lampela (eds.) Huumorin skaalat. Esitys, tyyli, tarkoitus, 95–107. Helsinki: SKS.

Hilvert-Bruce, Zorah, James T. Neill, Max Sjöblom & Juho Hamari. 2018. “Social Motivations of Live-Streaming Viewer Engagement on Twitch.” Computers in Human Behaviour 84, 58–67.

Howkins, John. 2013. The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas. London: Penguin Books.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Jokinen, Timo & Risto Linturi. 1985. MSDOS ja PCDOS käyttäjän opas. Espoo: Amersoft.

Jørgensen, Kristine. 2017. “Newcomers in a Global Industry: Challenges of a Norwegian Game Company.” Games and Culture. Published August 2, 2017.

Jørgensen, Kristine, Ulf Sandqvist & Olli Sotamaa. 2017. “From Hobbyists to Entrepreneurs: On the Formation of the Nordic Game Industry.” Convergence 23 (5), 457–476.

Kent, Steven L. 2001. The Ultimate History of Video Games: From Pong to Pokémon and Beyond. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Kultima, Annakaisa & Jouni Peltokangas. 2017. Ylistetyt, rakastetut, paheksutut, unohdetut: Avauksia suomalaisen pelihistorian laajaan kirjoon. Tampere: Mediamuseo Rupriikki.

Kuorikoski, Juho. 2014. Sinivalkoinen pelikirja: Suomen pelialan kronikka 1984–2014. Saarijärvi: Fobos Kustannus.

Kuorikoski, Juho. 2015. Finnish Video Games: A History and Catalog. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Kuorikoski, Juho. 2017. Commodore 64: Tasavallan tietokone. Helsinki: Minerva.

Kuorikoski, Juho. 2018. Pelitaiteen manifesti. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Kushner, David. 2003. Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture. New York: Random House.

Kushner, David. 2012. Jacked: The Outlaw Story of Grand Theft Auto. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

Lappalainen, Elina. 2015. Pelien valtakunta: Miten suomalaiset peliyhtiöt valloittivat maailman? Jyväskylä: Atena.

Latorre, Óliver Pérez. 2013. “The European Videogame: An Introduction to Its History and Creative Traits.” European Journal of Communication 28 (2), 136–151.

Mäyrä, Frans, Tanja Sihvonen, Janne Paavilainen, Hannamari Saarenpää, Annakaisa Kultima, Timo Nummenmaa, Jussi Kuittinen, Jaakko Stenros, Markus Montola, Jani Kinnunen & Antti Syvänen. 2010. “Monialainen pelitutkimus.” In Sami Serola (ed.) Ote informaatiosta: Johdatus informaatiotutkimukseen ja interaktiiviseen mediaan, 306–354. Helsinki: BTJ Kustannus.

Niipola, Jani. 2015. Pelisukupolvi: Suomalaisen peliteollisuuden tarina Max Paynesta Angry Birdsiin. Helsinki: Johnny Kniga.

Nikinmaa, Joona. 2012. “Kun ohjelmistopiratismi saapui Suomeen: Ohjelmistopiratismi kuluttajien keskuudessa vuosina 1983–1985.” In Jaakko Suominen, Raine Koskimaa, Frans Mäyrä & Riikka Turtiainen (eds.) Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja 2012, 11–20. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto.

Onosko, Tim. 1983. Kaikki Kuusnelosesta: Commodore 64. Translated by Veikko Rekunen & Tuomo Hakala. Espoo: Amersoft.

Paju, Petri. 2009. “Computer Industry as a National Task: The Finnish Computer Project and the Question of State Involvement in the 1970s.” In John Impagliazzo, Timo Järvi & Petri Paju (eds.) HiNC 2007: History of Nordic Computing 2, 171–184. Berlin: Springer.

Pasanen, Tero. 2011. “‘Hyökkäys Moskovaan!’—Tapaus Raid Over Moscow Suomen ja Neuvostoliiton välisessä ulkopolitiikassa 1980-luvulla.” In Jaakko Suominen, Raine Koskimaa, Frans Mäyrä, Olli Sotamaa & Riikka Turtiainen (eds.) Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja 2011, 1–11. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto.

Pettus, Sam. 2013. Service Games: The Rise and Fall of SEGA: Enhanced Edition. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Publishing.

Porter, Michael E. 1990. Competitive Advantage of Nations. New York: Free Press.

Porter, Michael E. 1998. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York: Free Press.

Reunanen, Markku, Mikko Heinonen & Manu Pärssinen. 2013. “Suomalaisen peliteollisuuden valtavirtaa ja sivupolkuja.” In Jaakko Suominen, Raine Koskimaa, Frans Mäyrä, Petri Saarikoski & Olli Sotamaa (eds.) Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja 2013, 13–28. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto.

Reunanen, Markku & Manu Pärssinen. 2014. “Chesmac: ensimmäinen suomalainen kaupallinen tietokonepeli—jälleen.” In Jaakko Suominen, Raine Koskimaa, Frans Mäyrä, Petri Saarikoski & Olli Sotamaa (eds.) Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja 2014, 76–80. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto.

Reunanen, Markku. 2017. Times of Change in the Demoscene: A Creative Community and Its Relationship with Technology. PhD Dissertation. Turku: University of Turku. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-6717-9.

Rogers, Everett M. & Judith K. Larsen. 1984. Silicon Valley Fever: Growth of High-Technology Culture. New York: Basic Books.

Ruohonen, Mikko. 1986. Työkaluohjelmat. Espoo: Amersoft.

Ruohonen, Mikko & Markku Tuomola. 1985. Yrittäjä ja mikrot: Mikro-ohjelmat, niiden hankinta ja toimivuus. Espoo: Amersoft.

Ryan, Jeff. 2011. Super Mario: How Nintendo Conquered America. New York: Portfolio/Penguin.

Saarikoski, Petri. 2004. Koneen lumo: Mikrotietokoneharrastus Suomessa 1970-luvulta 1990-luvun puoliväliin. Saarijärvi: Gummerus.

Saarikoski, Petri & Jaakko Suominen. 2009a. “Pelinautintoja, ohjelmointiharrastusta ja liiketoimintaa: Tietokoneharrastuksen ja peliteollisuuden suhde Suomessa toisen maailmansodan jälkeen.” In Jaakko Suominen, Raine Koskimaa, Frans Mäyrä & Olli Sotamaa (eds.) Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja 2009, 16–33. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto.

Saarikoski, Petri & Jaakko Suominen. 2009b. “Computer Hobbyists and the Gaming Industry in Finland.” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 31 (3), 20–33.

Saarikoski, Petri, Jaakko Suominen & Markku Reunanen. 2017. “Pac-Man for the VIC-20: Game Clones and Program Listings in the Emergent Finnish Home Computer Market.” Well Played 6 (2), 7–31.

Sandqvist, Ulf. 2012. “The Development of the Swedish Game Industry: A True Success Story?” In Peter Zackariasson & Timothy L. Wilson (eds.) The Video Game Industry: Formation, Present State, and Future, 134–153. New York: Routledge.

Sheff, David. 1993. Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World. New York: Random House.

Sihvonen, Jukka. 1991. “Uunolandia.” In Jukka Sihvonen (ed.) UT: Tutkimusretkiä Uunolandiaan, 12–26. Helsinki: Kirjastopalvelu.

Sihvonen, Tanja. 2009. Players Unleashed! Modding The Sims and the Culture of Gaming. Annales Universitatis Turkuensis B 320. Turku: Turun yliopisto.

Sotamaa, Olli. 2010. “When the Game Is Not Enough: Motivations and Practices Among Computer Game Modding Culture.” Games and Culture 5 (3), 240–255.

Suominen, Jaakko. 2017. “How to Present the History of Digital Games: Enthusiast, Emancipatory, Genealogical and Pathological Approaches.” Games & Culture 12 (6), 544–562.

Švelch, Jaroslav. 2013. “Say It with a Computer Game: Hobby Computer Culture and the Non-Entertainment Uses of Homebrew Games in 1980s Czechoslovakia.” Game Studies 13. Accessed September 6, 2018.

Švelch, Jaroslav. 2018. Gaming the Iron Curtain: How Teenagers and Amateurs in Communist Czechoslovakia Claimed the Medium of Computer Games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Swalwell, Melanie. 2005. “Early Games Production in New Zealand.” In Proceedings of DiGRA 2005 Conference: Changing Views – Worlds in Play. Digra Digital Library.

Swalwell, Melanie. 2009. “Towards the Preservation of Local Computer Game Software.” Convergence 15 (3), 263–279.

Tiitta, Allan. 1997. Ajan ja tiedon taitaja: Weilin+Göös 1872–1997. Helsinki: WSOY.

Tuomi, Ilkka. 1987. Ei ainoastaan hakkerin käsikirja. Helsinki: WSOY.

Wade, Alex. 2016. Playback – A Genealogy of 1980s British Videogames. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Wiio, Osmo A. & Antti Wiio. 1985. CP/M opas. Espoo: Amersoft.

Wilkins, Chris & Roger M. Kean. 2015. The Story of US Gold: A Very American, British Software House. Kenilworth: Fusion Retro Books.

Wilkins, Chris & Roger M. Kean. 2017. The History of Ocean Software. Kenilworth: Fusion Retro Books.

Ylänen, Henna. 2017. “Kansakunta pelissä: Nationalismi ja konflikti 1900-luvun alun suomalaisissa lautapeleissä.” Ennen ja nyt: Pelit ja historia 2017 (1). Accessed September 10, 2018.

Zackariasson, Peter & Timothy L. Wilson, eds. 2012. The Video Game Industry: Formation, Present State, and Future. New York: Routledge.

Notes

[1] The games published by Amersoft have become rare collector’s items. Their original versions have sold in online auctions for prices ranging from 100 to 300 euros. A more detailed exploration of the games can be achieved at the Finnish Museum of Games in Vapriikki, Tampere, or through Commodore 64 emulators. Some games are also available in YouTube videos.

[2] Examples include the American healthcare giant Johnson & Johnson, which published a promotional game called Tooth Protectors in 1983, developed by DSD/Camelot, as well as Coca-Cola’s Pepsi Invaders (1983), a clone of Space Invaders.

[3] In 1985, the Commodore 64 was not the cheapest home computer nor was it the most expensive. Its updated version, the Commodore 128, cost 3,200 Finnish marks, while Spectrum models ranged from 1,400 to 1,800 marks, Spectravideos from 1,600 to 4,900 marks, and Amstrad CPCs from 6,000 to 9,000 marks. The cheapest Atari models cost between 1,000 and 2,000 marks, while the most expensive, the Atari 520 ST, was 9,000 marks (Printti 10/1985; 20/1985). By the end of 1987, the Commodore 64, with a disk drive, cost around 2,000 marks (Printti 20/1987).

[4] PCI-Data was an experienced player in the domestic home micro market. Until the mid-1980s, it was part of Comico Oy, which imported computers from Sharp, Apple, and Commodore. After separating, PCI-Data held a monopoly on Commodore computers, which it exploited in its criticized pricing policy (Saarikoski 2004, 59, 65, 117).

[5] A number of foreign, primarily British, gaming magazines spread to Finland, such as Computer and Video Games (CVG) and Zzap!64.

[6] Telmacs were home computer kits produced by the Finnish company Telecras and powered by 8-bit RCA-1802 processors.

[7] Before the discovery of Chesmac, it was believed that the oldest commercial Finnish game was Amersoft’s Mehulinja (1984) for the VIC-20 computer. The game won a programming competition organized by Poke & Peek! magazine in 1983 (Poke & Peek! 2/1984; Reunanen & Pärssinen 2014, 76).

[8] In addition to Amersoft, games were also published by Teknopiste, Ideameca, ALA Software, T & T Productions, and Oy Hedengren Ab.

[9] See Astex 64, Crash 64, and Delta 64. The publisher was Amersoft.

[10] Fasoulas’s first published game was a Pac-Man clone for the VIC-20, released as a program listing in MikroBitti (1/1984) (see Saarikoski et al. 2017).

[11] Following the popularity of Sanxion, Fasoulas’s next games, Delta (Thalamus 1987) and Quedex (Thalamus 1987), also made it onto the same list.

[12] Sanxion briefly entered the top 30 best-selling games in Finland, ranking 26th in November and 21st in December of that year (Printti 20/1986, 19).

[13] See Videogames.fi, http://www.videogames.fi. The number includes various versions translated for different Commodore models and country-specific localizations published under names different from the original game.

[14] Text-based games emerge as one of the peculiarities of Finnish games from the 1980s. Coding their parsers (i.e., interfaces that simplify player input of text commands) has been quite labor-intensive due to the number of grammatical cases in our language. These games were primarily published on C-cassettes or as code listings. Worldwide, this genre enjoyed brief popularity in the early 1980s.

[15] See the Finnish Commodore Archive, http://www.ntrautanen.fi/computers/commodore/arkisto.htm [Link no longer active].

[16] The company’s name was Amer-Tupakka Oy until 1973. In 2005, the company changed its name to Amer-Sport Oyj as it focused on selling sporting goods.

[17] Weilin-Göös belonged to the Amer Group until 1995, when it was sold to WSOY publishers.

[18] Gunnar Nyström began his term as CEO on June 1, 1984 (Tietokone 4/1984, 114), but Amersoft was only registered in the business registry on October 4, 1984.

[19] See Campbell-Kelly’s (2003) tripartite division of the software industry: 1) software subcontracting; 2) professional software; and 3) mass-market software.

[20] Amersoft imported at least the following titles: Antarctic Adventure (Konami 1983), Driller Tanks (Hudson Soft Company 1983), Shark Hunter (Electric Software 1984), Le Mans (Electric Software 1984), Ninja (Kuma Computers 1984), 007: License to Kill (Domark 1985), Theatre Europe (Personal Software Services 1985), and Zaxxon (Coleco Industries 1985).

[21] Professor Mikko Ruohonen from the Tampere University worked as an entrepreneur in the mid-1980s, and Amersoft published two of his non-fiction books. The book Entrepreneurship and Micro: Micro-Programs, Their Procurement, and Functionality (1985) was based on a study and book proposal made by Ruohonen and his colleague Tuomo Markkula, while the subject of Utility Programs (1986) came from Amersoft’s suggestion, according to Ruohonen (Ruohonen, interview 2018). Thus, as with games, Amersoft made publishing decisions based on proposals made by authors, but the company also commissioned books from familiar authors. In the early 1980s, there was a significant demand for non-fiction books on information technology, but also competition, as several publishers released translations as well as original works by Finnish authors.

[22] See the publishing agreement between Jyri Lehtonen and Amersoft dated January 17, 1985, see http://videogames.fi/vgfi/index.php/Delta_16.

[23] According to the Bank of Finland’s cost-of-living index-based currency calculator, 10,000 marks in 1985 corresponds to approximately 4000 euros in 2024 currency.

[24] The game Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle was actively advertised following its release. Amersoft was, however, unable to provide the gaming press with materials before the actual release, as the game cassettes had to be made twice due to copy protection failures (Kinnunen, interview 2014).

[25] Examples include Ghostbusters (Activision 1984), Bruce Lee (US Gold 1984), Rambo (Ocean 1985), Commando (Elite 1985), Miami Vice (Ocean 1986), and Knight Rider (Ocean 1986), which were among the best-selling computer games in Finland in 1985 and 1986 (see e.g., Printti 20/1985, 5; Printti 4/1987, 19).

[26] Amersoft’s games were covered in the press in three different ways. Short articles discussed their content (see e.g., Printti 18/1986), while game reviews were rare. For example, Afrikan tähti was reviewed in Printti magazine issue 20/1985, and Yleisurheilu in MikroBitti issue 4/1985. The reviews emphasized the domestic nature of the games but also criticized their high prices. The third method was advertisements. Games were advertised either separately or as part of the company’s other product range (see e.g., Printti 1/1984; MikroBitti 3/1984). The advertising campaign for Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle received the most marks (see e.g., MikroBitti 12/1986; Printti 18/1986).

[27] For example, Petteri Bergius reviewed the game Le Mans 2 (Electric Software 1985) for MikroBitti (11/1985, 69). Bergius’s review cannot be accused of favoring partners. Amersoft imported Electric Software’s games, but in the review, the game received only two stars.

[28] Risto Siilasmaa, known for his work at F-Secure and Nokia, is certainly the most well-known former employee of Amersoft. Siilasmaa worked as a summer intern at the company in 1984 (Petteri Bergius, interview 2014; Nyström, interview 2014).

[29] Toptronics is a rare example of a Finnish company established in the 1980s that made game importing a profitable business. The company later became the market leader in the Nordic countries (Kuorikoski 2017, 121).

[30] For many young game developers, having quality content was less important than getting their games onto magazine pages in the form of code listings (Kuorikoski 2017, 121).

[31] This does not mean that all of Amersoft’s games were of poor quality. The reviews of the games were quite divided. Yleisurheilu received four stars in a review by MikroBitti (4/1985, 64), although its graphics received criticism. The reviewer believed the game would be a sure hit, despite not being groundbreaking. However, the advertisement for Yleisurheilu only stated that it was “a true sports experience for home computers.” By contrast, Afrikan tähti received only two stars in Printti’s review (20/1985, 25). The game’s graphics were praised, but its playability fell far short of the original board game.

[32] According to one estimate, as much as 90% of the software used between 1983 and 1985 consisted of illegal copies (Tuomi 1987, 152).

[33] The Copyright Act on literary and artistic works (897/1980) allowed copying for private use.

[34] Jukka O. Kauppinen, a pioneer of the Finnish demoscene and games journalism, remarks sarcastically in Juho Kuorikoski’s book Sinivalkoinen pelikirja (The Blue-and-White Game Book, 2014, 37) that the only state support for Finnish game development in the 1980s came through the social welfare office. It is also reasonable to assume that many hobby projects were “funded” with the help of student aid or unemployment benefits.

[35] Tekes (the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation) began supporting the Finnish game industry on a small scale through the Digital Media Content Products program (1997–1999). This was followed by USIX (New User-Centered Information Technology, 1999–2002), SPIN (Software Products, 2000–2003), FENIX (Interactive Information Technology, 2003–2007), and Verso (Vertical Software Solutions, 2006–2010) (Hiltunen & Latva 2013). In the Skene – Games Refueled program (2012–2015), more than 50 Finnish game companies received a total of 28 million euros in funding (Neogames 2015, 3).