Campaign communication, entertainmentization, Instagram, personalization, political branding, presidential election

Elisa Kannasto

elisa.kannasto [a] seamk.fi

PhD, Head of Degree Programme, Master School

Seinäjoki University of Applied Sciences

How to cite: Kannasto, Elisa. 2025. ”Instagramming Persona in the 2024 Finnish Presidential Election”. WiderScreen 28 (1–2). https://widerscreen.fi/numerot/1-2-2025-widerscreen-28-numerot/instagramming-persona-in-the-2024-finnish-presidential-election/

Political campaigns are shaped by media. Social media allows politicians to manage their publicity, but it also requires skills to engage with constituents and encourage voting. Politicians pursue various tactics to attract and influence constituents on different platforms. In a persona-centric presidential election, candidates must maximize visibility and persuade voters. This study examines how presidential election candidates Alexander Stubb and Pekka Haavisto built their political personas through personalization and entertainment during the 2024 campaign. The analysis focuses on entertaining forms like emotional appeal, authenticity, visual aesthetics, and lifestyle integration that were used on their Instagram accounts. Instagram, as a recently politicized platform in Finland, seemed to serve as a central arena for constructing the presidential persona. While both candidates had unique styles and tactics to showcase their strengths and preferences in public performances and communication, elements of entertainmentization can be found in both profiles. These elements include glimpses of the private sphere and the campaign backstage, humour, social media trends, engaging content, entertaining event types and their shares of participating to entertaining formats in traditional media.

Over the past two decades, political communication has been significantly shaped by the emergence of social media platforms. In political communication this has strengthened the debate on what scholars call the entertainmentization of politics, where political content increasingly mirrors the logic of commercial media entertainment (Herkman 2008; Karvonen 2009). Often the entertainmentization of politics has been connected to the personal lives of politicians and media has made public entertainment out of several relationship scandals of politicians (Herkman 2011, 10; Isotalus 2017). This together with the persona orientated communication on social media (see Marshall, Moore & Barbour 2019; Enli & Skogerbø 2013) has also sparked discussion on personalization of politics (van Aelst, Sheafer & Stanyer 2012; Kannasto, Paatelainen & Isotalus 2023).

Instagram, with its emphasis on visual storytelling, has become a central platform where political figures craft personalized, emotionally resonant content to connect with voters. The platform, showcasing a wide array of influencers promoting beauty products and lifestyle, has stabilized its position as a political arena (Kannasto 2025b), where politicians and parties, alongside influencers, use visual communication and trends to attract attention to their cause and opinions. This trend was particularly evident in the 2024 Finnish presidential election campaign, in which Instagram served not only as a campaign tool but as a strategic arena shaping candidates’ communication logic. The profiles on social media do not just present candidates and their followers but collect central campaign strategies and shared information, create campaign atmosphere (Kannasto & Pöyry 2025), direct event planning, host live discussions and promote candidate-constituent interaction.

The establishment of social media as a central arena for campaign communication (see Laaksonen, Kannasto & Knuutila 2025) has increased various forms of entertaining communication and expanded their publicity (Klinger & Svensson 2015). This has manifested in, for example, portrayals of private life, such as videos of hobbies or family moments, content describing a politician’s typical day, backstage portrayals of the political profession, personal likes and attributes, and performances in situations that are not typical of the political role. While social media offers opportunities for personal and engaging communication with audiences (Enli & Skogerbø 2013), Finnish politicians have typically adhered to topic-orientated communication (Kannasto et al. 2023).

However, the candidate-orientated nature (see von Schoultz & Strandberg 2024) and national perspective of the presidential elections require candidates to utilize various forms of publicity and seek the attention and votes of the audience in multiple ways. Herkman (2011) explores how the entertainmentization of politics influences campaign messaging in Finland. He argues that the presentation of politics as a form of entertainment, combined with social media’s visual language, has changed the way political communication is consumed. This has led to campaigns that are as much about performing a relatable personality as they are about policy, with candidates carefully curating their public image to appeal to both emotion and reason. The added social media communication may have led to more attention and interest towards politicians, which may have also brought increased political knowledge that Rapeli’s (2025) findings show for the young, low-educated and low-income respondents in 2020 compared to 2008.

With this text, I open a discussion on how Instagram may serve as a central platform in politics for constructing engaging political personas. By using the concepts of entertainment and personalization from political communication research, the analysis focuses on the 2024 presidential election campaign in Finland and the two leading candidates, Alexander Stubb and Pekka Haavisto. Through qualitative content analysis, the study investigates how these candidates constructed political personas and framed their campaign communication during the 2024 election campaign. The analysis focuses on discursive strategies that highlight emotional appeal, authenticity, visual aesthetics, and lifestyle integration.

Herkman (2011) highlights that election publicity is intermedial and requires multi-channel communication that considers different audiences. While a multi-platform approach could construct a more holistic view on campaign communication, this study focuses on Instagram as a central arena of all campaigning. The importance of Instagram in the Finnish campaign communication for politicians was solidified during the 2023 Parliamentary election (Kannasto 2026). Therefore, it is justified to map out its relevance in the following presidential election, in addition to the platform’s undeniable position in persona construction (Marshall Moore & Barbour 2019). The hybrid media environment (see Chadwick 2013) of the 2020s calls for an update to Herkman’s (2011) examination of political publicity, which this study approaches from the perspective of entertainment. This study aims to examine the forms of entertainment in the Instagram campaigning of the 2024 presidential candidates. The research questions are as follows: 1) How was Instagram used in the presidential campaign of the two leading candidates? 2) What kind of entertaining campaign content was seen in the elections?

The Finnish Presidential elections provide a compelling case due to the significant role of social media in these elections. All candidates spread their campaigns to the most used social media platforms. In the 2023 Parliamentary elections, 23 % of voters followed election campaigning significantly on social media (Isotalo et al. 2023). Another interesting point is the candidate-centered orientation in Finland. First, Finnish voters tend to shift their votes between elections, and in the parliamentary campaigns candidates compete even against their own party list candidates (Söderlund 2023). Second, since the President in Finland holds less power in internal politics, the role is often seen as more representative and less crucial for party representation. Therefore, the presidential campaigns have a strong focus on personas. This fits well with social media, which has been suggested to encourage candidates to self-personalize due to its nature and logic (Enli & Skogerbø 2013; Metz, Kruikemeir & Lecheler 2020).

Media and Entertainmentization of Politics

In Finnish politics, elements of entertainment have taken various forms, from television entertainment shows to intimate media performances (Herkman 2011; 2010; 2008), and now to entertaining ”my day” -videos and TikTok trends. In political campaigning, with the need to appeal widely to constituents, different artists have been brought to perform at campaign events, celebrities publicly endorse candidates, candidates appear in television entertainment shows, and they open up about their lives and personal relationships in magazines. While these elements remain essential parts of campaigning, new elements brought by social media have been introduced. In platforms like Facebook, Instagram and TikTok, politicians can use their profiles to connect with the public through personal posts, synchronous and asynchronous comment threads, private messages and live broadcasts. While at first social media seemed to be more of a new arena for one-way information channel for Finnish politicians (Nelimarkka et al. 2020), audiovisual platforms like Instagram and TikTok have brought new types of possibilities for candidate-constituent interaction. More visual communication and live broadcasts are used to create connection and seemingly authentic personas (Kannasto 2021). In addition, backstage glimpses and less formal representations of politicians have entered their campaign communication in social media.

The importance of the media for politicians is evident. Intermediality refers to the interconnectedness of different media forms and platforms in the dissemination of political messages. Herkman (2011) emphasizes that modern election campaigns must navigate a complex media landscape where traditional and new media intersect. Chadwick’s (2013) idea of hybrid media explains this further as traditional media and social media complementing and feeding each other. Kannasto (2021) discusses added publicity, where politicians share beneficial traditional media stories of themselves in their own profiles, thus seeking more publicity for them (Paatelainen, Kannasto & Isotalus 2024). This intermedial approach allows campaigns to reach diverse audiences through various channels, enhancing the overall impact of their messages.

Intertextuality involves the relationship between different texts and how they reference or build upon each other. In the context of political campaigns, intertextuality can be seen in how candidates’ messages are echoed and amplified across different media platforms. For example, a candidate’s speech might be referenced in social media posts, news articles, and television programs, creating a web of interconnected content that reinforces the campaign’s key messages (Van Zoonen 2005, 12). By examining the interplay of intermediality, intertextuality, and hybrid media, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how these elements are used to communicate entertainment and public figures in political marketing and influence during the 2024 presidential campaign.

While the entertainmentization of politics and social media communication in politics often draw criticism for overshadowing topical issues or undermining the importance of politics, they can also bring new interest and audiences to political topics and politicians, and attract voters. By making politics more approachable, democracy may strengthen with more people participating in discussions and decision-making. For example, candidates with less resources have been found to make their way into politics with the help of social media. However, in the presidential elections, the leading candidate budgets ran well over a million and their brands were firmly grounded to their earlier established media visibility. The topic-orientated focus in Finnish politics (Kannasto et al. 2023; Isotalus 2017) also challenges candidates who try to establish themselves through pure celebrity politics. Nevertheless, there has long been a tradition that candidates also seek additional visibility with the help of entertainment. For example, entertainment shows like Tuttu juttu and entertainment magazines’ couple interviews have often presented political candidates during election seasons (Isotalus 2017; Herkman 2011).

Personalization in Finnish politics, as discussed by Pekka Isotalus (2017), and later also Elisa Kannasto (2021), illustrates how political figures are increasingly expected to perform their political identities in ways that are visually appealing and emotionally resonant. However, as also noted, personalization in Finnish politics has more to do with individuals representing political topics and agenda being narrated through them than with politicians’ private lives and personal qualities (Paatelainen, Kannasto & Isotalus 2024). There is a gap in research on Finnish presidential election campaigns and how significant the backstage scenes and visual politics are for persona construction in the age of social media. In addition, so far, studies covering election communication on social media in Finland have been connected to the parliamentary elections (Paatelainen et al. 2024; Nelimarkka et al. 2019) or municipal elections (Nieminen, Kannasto & Isotalus 2022).Considering that in 2024, the presidential election result was historically close, with only a 3.2 % difference between the candidates (Tilastokeskus 2024), more studies are also needed on presidential election campaigning. The small difference highlights the importance of successful campaigns, as well as the importance of analyzing and learning from them.

Social Media Campaign Communication

In general, political campaigns have seen a shift from emphasizing policy debates to focusing on individual candidates as brands, a shift that plays into the broader cultural expectations of authenticity and personal connection. Kannasto (2021) highlights that social media encourages Finnish politicians to frame themselves as ’real people’ through social media platforms, blurring the lines between their personal and political lives. In the broader context of social media’s role in politics, Instagram not only reflects the entertainmentization of political communication but also offers political discussion to the users. This phenomenon goes beyond the mere use of social media as a platform to communicate messages; it indicates a shift toward political branding, where politicians not only communicate but also entertain, blending political discourse with entertainment formats. While direct candidate-constituent interaction and connecting through private life content has been seen as one of the appealing points of social media campaigning (Peng 2021), Finnish politicians have often refrained from it (Nelimarkka et al. 2020; Kannasto 2021). Similar findings on politicians not discussing their private life have been found in 2014 and 2019 in the European Union elections (Russman, Klinger & Koc-Michalska 2024).

In Finland, presidential elections hold unique significance compared to the parliamentary elections, as the president is not just a political figurehead but a symbol of national unity and a key player in foreign policy. The representative importance of the elected president is often highlighted in the campaigns and public discussion during the presidential election, which often also touch on the candidates’ appearance, rhetoric skill, language skills, family, and values. Thus, unlike in parliamentary elections, where party affiliation dominates, Finnish presidential elections emphasize the individual candidate’s character, leadership qualities, and personal appeal. For example, the preceding President Sauli Niinistö was running as an independent candidate on his second term in 2018 to highlight his role as a candidate free from party ties. Similarly, Pekka Haavisto was running as a candidate of an electoral association in the 2024 election to break away from the ties of the political party. In Finland, the president is elected by direct popular vote for a six-year term, and their role is largely ceremonial but crucial in terms of shaping Finland’s international presence. However, the shift in defence policy and Finland’s NATO membership in 2023 brought more focus to national security and the president’s role during the 2024 presidential elections.

Historically, the communication in presidential campaigns in Finland have centered around mass media, but since the 2012 elections, social media has played an increasing role in voter engagement and candidate visibility (Kannasto 2026). However, it has remained unclear what type of content is effective in voter engagement and support as most studies seem to agree that strategies and results are highly individual between politicians (Kannasto 2021; 2025). Regardless, social media has been significant for candidates; in the 2011–2012 presidential campaign Pekka Haavisto was among the first candidates to utilize social media for campaigning. It has been argued that it was essential for him getting to the second round and truly challenging Sauli Niinistö in the election (Suominen et al. 2013, 168, 253). The campaign of Haavisto seemed to learn from the successful social media campaign of Barack Obama in 2008 and he mobilized a lot of supporters on Facebook. On the other hand, Alexander Stubb was the first Finnish politician to bring Twitter into Finnish politics and was publicly called the most active social media politician of his time (Hämäläinen 2017; Yle 16.6.2014).

Political figures are no longer just party representatives; they are media personalities who must manage their image, public perception, and personal narrative (Isotalus 2017; Kannasto, Paatelainen & Isotalus 2023). Moreover, the integration of personal life with political messaging on Instagram has reshaped how candidates are perceived, offering them a platform where they can craft authentic, relatable personas that are visually engaging and emotionally charged (Enli 2017; Peng 2021). By 2024, Instagram has stabilized its role as an essential tool for building political brands, particularly for candidates trying to reach new demographics and strengthen connections with their already existing ones (Kannasto 2026). Instagram’s role as a political tool reflects broader shifts in social media’s impact on political communication globally. Platforms like Instagram facilitate a more direct and personal form of communication between politicians and their constituents, allowing for the development of an individualized political brand. The Instagram presence of well-known political figures like Victor Orbán, Justin Trudeau, Santiago Abascal and Volodymir Zelenskyi has attracted wide research interest (Lalancette & Raynauld 2019; Sampietro & Sánchez-Castillo 2020; Szebeni & Salojärvi 2022; Plazas‐Olmedo & López‐Rabadán 2023).

Data and methodology

This study focuses on the Instagram posts of the two leading candidates who made it to the second round of the 2024 presidential elections, Alexander Stubb (National Coalition Party candidate) and Pekka Haavisto (electoral association candidate). In a larger upcoming study, the other parliamentary party candidates and their social media data will also be analyzed. The data for this study was collected as screenshots from the presidential candidates public Instagram profiles @alexander.stubb and @pekka.haavisto.

The data analyzed in this study consists of the feed posts from three months prior to the election day 10.2.2024. Between 10.11.2023-10.2.2024 Alexander Stubb published 444 posts and Pekka Haavisto 300 posts. These posts were analyzed using qualitative content analysis. The theoretical framework of the study relies on the blurring boundaries between politics and entertainment (Van Zoonen 2005, 12), the concept of hybrid media (Chadwick 2013, 89), and the intermediality of election communication (Herkman 2011).

Analysis

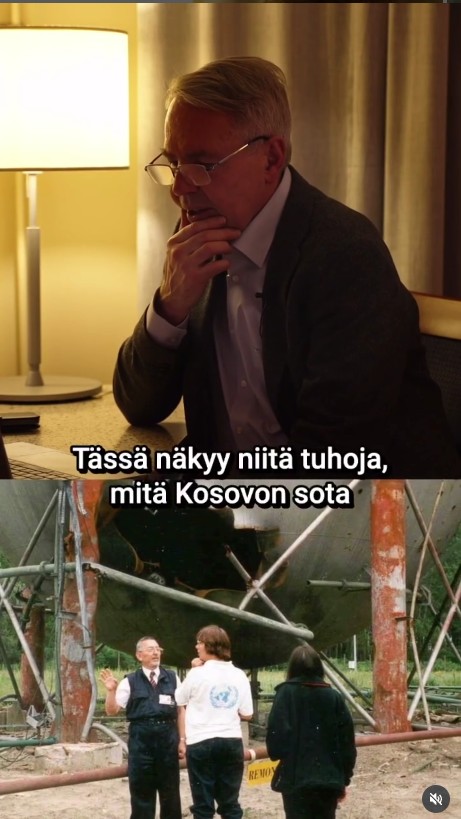

Both candidates communicated their professional backgrounds as an element of branding. These were built into short autobiographical clips or photos that sometimes also included humor in the storytelling. Pekka Haavisto focused on communicating his role in international politics both through videos (Image 1a, 1b) and personal photos and their captions: ”In this photo I am in one of the most dramatic situations as an EU Special Representative” (@pekkahaavisto 7.1.2024, translated by author). Haavisto highlighted situations of negotiations and peace keeping and the extensive experience he has in diplomacy. This way he was able to build up his profile as an experienced professional who is fitting to the role of the president and representing Finland in foreign politics. The data supports an earlier finding that politicians often use the element of professional background to claim authority and present expertise in their self-branding (Kannasto 2021).

Candidate Stubb did not include descriptions of his past political role in the same way as Haavisto, possibly because of the negative response to his previous political role which also came up in the media discussion around the speculation leading to his candidacy in the presidential election. His previous experience in the Finnish political scene includes a challenging government period. The data, as well as the presidential debates during the campaign, imply that Stubb wanted to highlight that the president’s role in diplomacy and foreign politics was more natural to him and aligned with his expertise and academic background. His campaign focused on these aspects rather than on previous political achievements or former role in domestic politics. When this experience was mentioned in the data, it mainly took place in the endorsements from his former political colleagues (Image 2).

The posts on Pekka Haavisto’s account showed a connection with culture and arts, highlighted his professional expertise as well as his international political experience in peace negotiations and defense politics, and presented endorsements from both cultural celebrities and ordinary citizens. Endorsements also played a smaller role in his Instagram feed than those posted on Stubb’s profile (Image 2). They generally appeared as selfies, rather than official statements of endorsement that had been created as a distinct type of post on Stubb’s profile. Both candidates had their own political networks of other politicians, which were used to construct their persona and supporter base (Image 3a, 3b).

The data highlights that both leading candidates had background in politics, earned media coverage easily and had their distinct follower and voter base. Thus, the main task in the campaigns seemed to be more about amplifying the messages, confirming the motivation and promises to the public and reminding the constituents what kind of representation they would get from each candidate. It seems that in both candidate’s cases, the various endorsements, public figures, and emotion provoking content were used to motivate constituents to join the candidate’s movement and to vote. In addition, the campaigns emphasized the strong will of both candidates not to highlight oppositions or engage in negative campaigning – both openly condemned negative statements and mobilization in their own campaigns.

Overall, Alexander Stubb’s posts showcased a profile featuring sports (Image 4a), Finnish nature scenery and activities, business life and athlete endorsements (Image 2), media performances, such as podcasts, entertainment television along with a more relaxed background portrayal with informal clothing (Image 3b), home setting photos and sport training (Image 5). This type of private life content can make the candidate more approachable, an ordinary person, which can be viewed positively especially in Finland, which represents a low hierarchy society. The wife of Stubb, Suzanne Innes-Stubb was included in the campaign through seemingly natural occasions where the couple participated in events together or Suzanne gave comments in videos. These added personality and humor to the campaign, for example when Susanne stated in a video that she would not say who she voted for because of the Finnish ballot secrecy. In addition, several photos highlighted the community atmosphere, with crowd appeal and smiling or “hype-like” people, emphasized by the number of crowd photos in the data.

The data from the account of @pekkahaavisto included several images presenting Haavisto’s spouse Antonio Flores, who participated in the campaign by, for instance, hosting events. They also attended events and interviews as a couple. One example was a video series of short clips where they would answer intimate or humorous questions that started with “Which one of you is most likely to?” (Image 6). These posts together with several posts depicting only Haavisto or him with someone else created an intimate atmosphere in Haavisto’s feed compared to Stubb, whose posts often included crowds and several people and fewer, selected portrayals of only him or him with his wife. While the data in @alexstubb included several glimpses of the private sphere (Image 5; Kannasto 2021), Haavisto also commented on the private in, for example, a post explaining his clothing style: ”The deeper meaning of my choice of ties has been pondered in both the blue and red tie. The reason for the choices is not a political stand but is standing right here. Luckily, I have a good critic at home” (@pekkahaavisto 8.2.2024).

The two presidential candidates used various platforms to spread their messages but often brought the content on their Instagram that seems to function as a central communication space of diverse forms and styles of content. In the published posts, content that can be interpreted as entertaining was found in both the relaxed content and official media formats intended for broad audiences (Street 2012, 34). Both candidates also published their own media, vodcast (podcast also offering a video from) “A-talk” by Alexander Stubb and an audio form “Saturday letter” by Pekka Haavisto which were shared and marketed in their Instagram. In “Alex Talk,” Stubb discussed with known Finnish people like artist Samu Haber and social media influencer Auri Kananen (Image 7a), which could also engage the followers of these celebrities. These can be viewed as similar to celebrity endorsements. Haavisto’s Saturday letter included story telling from past experiences and views about current issues that were meant to represent the candidate’s persona.

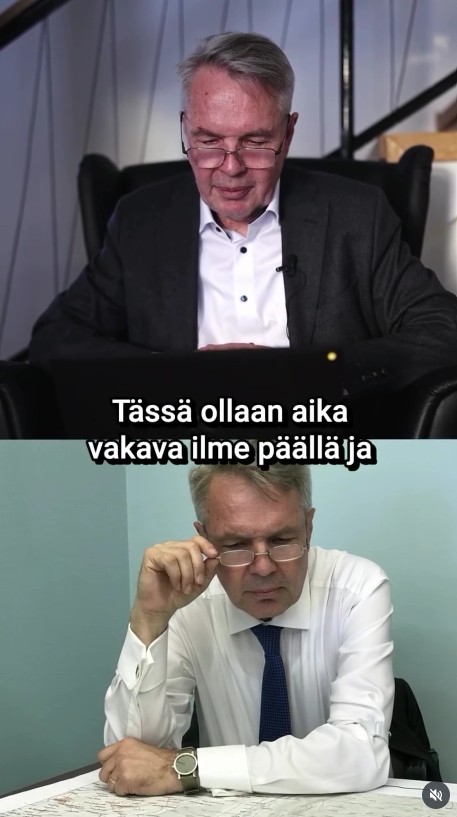

The data implies that both candidates built their persona and promoted engagement also through selective glimpses to the backstage (see Marshall, Moore & Barbour 2019; Kannasto 2021) of the campaign trail (Image 5, 6, 8a, 8b). By bringing these non-public images to their audiences, the candidates may try to build a closer connection and give the impression that the public gets to participate in their personal life. These types of backstage images are more rare than the public performances and media images that are available to anyone. For a politician they can offer an asset to engage more followers; they function as sort of promises to the audience that they see what is actually happening – not just what is public. However, as images 8a and 8b show, even these are carefully crafted in the feed and selected to deliver a specific message; the need to rest like anyone else in the midst of hard work and the need to prepare for media performances.

The forms of entertainment in the campaign can be classified using both media formats and content types, including for example traditional women’s magazine relationship interviews, television entertainment programs (Dahlgren 2009, 56), as well as new forms such as participating in TikTok trends and podcast appearances. Additionally, traditional market events were renewed by creating a campaign atmosphere with, for example, sports events (Image 4a). Campaigns also utilized various public figures who functioned as endorsers and content creators on their social media accounts (Enli & Skogerbø 2013). In addition, well-known politicians became valuable networks to feature in selfies and endorsement posts with the candidates (Image 3a, 3b, 4b). Last, backstage glimpses offered descriptions from the campaign trail (8a, 8b), introductions to the candidates’ personal preferences, and feeling-orientated posts about campaigning and the public.

Results

This study examined the forms of entertainment seen in the 2024 presidential campaign focusing on Instagram. The platform was used to spread traditional media content, performances on debates or other television shows, portray public campaign events and appearances and to share more personal moments and feelings that were fitted into the visual communication mode of Instagram. While the posts in both accounts in the data mainly followed political everyday settings already typical for the Finnish political Instagram (see Lindholm, Carlson & Högväg 2021), they also show the development and stretching boundaries of private and professional (see Kannasto 2021) that have been seen in the politicized Instagram in Finland.

The data shows that the two candidates and their Instagram posts differed in style, portrayal of expertise, lifestyle content, endorsement categories, included personas, and networks. For example, while Haavisto would often be represented in photos wearing a suit and in official settings, the photos of Stubb also included the backstage setting and relaxed outlook. This may also be the result of the sports dimension in Stubb’s campaign; the events included cross country skiing and other exercise activities while Haavisto’s campaign included cultural events, like concerts and his DJ performances.

While aiming to attract the majority of constituents in Finland, the distinct styles in reality appeal to different demographics. However, it is noteworthy that because of their extensive experience in publicity and politics, both candidates had well known recognizable personal brands and they were the leading candidates in the presidential race from the start. This may have influenced the type of content and the ease in selection of content and limiting certain topics. It also needs to be recognized that both candidates were experienced performers with the media. Simultaneously both candidates already had a dedicated supporter base in the beginning of the campaign, so the campaigns were more about emphasizing the selected brand elements instead of building them from scratch. Both candidates also had visible networks and political capital that they could utilize in the campaign. This emphasis is evident, for example, in posts that highlight professional expertise.

Discussion

The data from the 2024 election demonstrated how candidates like Stubb and Haavisto can use Instagram to shape their public personas. Both candidates used the platform for curated posts that showcased their personal values, interests, and lifestyles, in addition to their political messages. These could be shaped as entertainment by choosing the format, adding visual focus or formatting the content into a private sphere or entertaining style. Stubb’s campaign, for instance, focused on appealing to both younger and older demographics, using visuals to emphasize his leadership capabilities while also presenting relatable, behind-the-scenes moments. The campaign theme “Together” was emphasized with displaying crowds, creating events where people were in a good mood, for example the joint skiing and walking events. Haavisto, in contrast, leveraged his Instagram presence to emphasize personal connections and emotional engagement with followers, presenting a narrative that was as much about humanizing himself as it was about his policy agenda. The photos concentrated on Haavisto alone or him with another person, portraying more intimate connections and highlighting political profession and background.

The findings on both candidates support earlier study on the Instagram of Zelenskyi, where he was found to strategically combine the backstage with the professional settings, and to use the platform tools that support communication (Sampietro & Sánchez-Castillo 2020). Both approaches also support Kannasto and Pöyry’s (2025) findings on social media mood-setting in campaigns and their difference between individual politicians. This may be because, as Bossetta and Schmøkel (2023) conclude, different audiences respond and reward the emotion from politicians differently on different platforms. While the data implies cross posting between platforms, it must be noted that the candidates in question may also seem different if a different platform was chosen as the focus point.

Drawing on the theory of political personalization (Langer 2010; van Aelst et al. 2012), the data implies that Instagram facilitates the branding of candidates as individuals – political figures who are constructed and perceived as multi-dimensional personas. Karvonen (2009) has described this type of focus and attention on individual politicians as the entertainmentization of politics. Each candidate seemed genuine, highlighting their personal preferences making them also this way approachable and relatable to those sharing the same values. This trend has reshaped campaign strategies, where candidates are required to create a cohesive, appealing image that resonates emotionally with voters. For example, the elements presented on Instagram for Alexander Stubb seem to have been strategically planned to serve Instagram as a central publicity forum. The events attract crowds which can then be shown in the imagery, convenient traditional media clips can be used to highlight appealing personal representations and along with high quality studio images, quick snapshots of the sleeping candidate on the back seat of the car bring a humane perspective to the audience.

Instagram also serves as an arena for added exposure (see Kannasto 2021) in the presidential campaign; the platform affords the candidates to share other media content, to control their representations through edits and other tools, to promote interaction, and to earn media visibility with the content they publish. This in turn highlights Herkman’s (2008) conclusions on mediatization and personalization and suggests that the transformation has even deepened – in 2024 campaign tactics are deeply connected with media and communicated through so much that even live meetings may carry an undertone of strategic media broadcasting. At the same time, entertainmentization becomes essential – drawing attention while doing and debating politics may be vital with intertwining political and media logic and winning the battle for attention. This interplay of intermediality, intertextuality and hybrid media challenges studying the campaigns, as content becomes almost untraceable to its origins and highly interconnected. However, in the presidential campaigns of Haavisto and Stubb, Instagram seemed like a central meeting point, the digital campaign tent with the essential campaign content unifying endorsements, public events, backstage stories, media performances and candidates’ feelings and representations.

The data implies that visual storytelling and emotional engagement are becoming central strategies in modern campaigning, especially in candidate-centered campaigns like the presidential campaign. When political topics seem complicated and narrow in scope, even far from the constituent’s everyday life, or especially if differences of opinion seem minimal, it may be more appealing and effective to discuss lifestyle, portray values through personal life (c.f. Kannasto 2021) and focus on presenting political expertise through background presentations and career narration instead of political arguments. In Finland, the president’s role is not tightly connected with domestic politics, for example taxation, health care or employment and the candidates seemed to make sure not to touch those issues to avoid any unnecessarily lost votes. In addition, in a multi-party system the differences between candidates on topic issues falling under the presidential rule may seem insignificant with everyone promoting the national interest and caution in world politics and highlighting the role of parliamentary representation in domestic policy so the big separation points are bound to remain in persona representations and brand. This adds the importance of visibility and publicity for the candidates so the strategies may also focus on added exposure instead of political influence during the campaign. The focus on decision-making and policy will come later.

As the data indicates, the fear of entertainment possibly overshadowing political agenda and affecting decision making also has its place in Finland. Therefore, more studies are needed to explore the engagement and possible effects on voting of the increased social media campaign. It also remains essential to map out the transformation in styles of social media campaigning. Especially with the fragmentation of social media communications and the focus being directed to and through various platforms forces to add platform-specific and comparative research that also focuses on the highly multimodal content and strategies behind producing it. The added professionalism in political communication focusing on campaign times in Finland (Kannasto 2025) would also need to be studied more to understand the effects of budget and voting results. While social media seems to steer and reshape campaigning, the audience needs more understanding in what and how strategies are formed and executed to gain power in decision-making and society.

The 2024 Finnish presidential election, viewed on Instagram and the concept of political branding, illustrates how social media platforms can serve as central arenas where personal narratives, branding, and entertainment intersect, ultimately shaping electoral outcomes. Social media brings the candidates to the most intimate space of every constituent; content is browsed everywhere where individuals take their phones. Through humane images, hype crowd portrayals and videos where the candidate speaks directly to the camera, the candidates can break the barriers of official communication by mediating an almost intimate direct candidate-constituent connection where the voter can feel like being present in every campaign event and the community created around the candidate. It remains to be seen how strong of a position entertainment has on politics or if the focus should rather be on studying professionalization and its effects in political communication (c.f. Herkman 2008; Kannasto 2025). The current trend seems to imply that social media attracts more entertaining content. And as parties and politicians continue to look for ways to draw attention and engagement (Kannasto 2025), new strategies, styles and attempts continue to push the traditional norms of political communication.

References

All links verified 6.8.2025.

Data

@alexstubb Instagram feed 10.11.2023-10.2.2024.

@pekkahaavisto Instagram feed 10.11.2023-10.2.2024.

Literature

Bossetta, Michael & Rasmus Schmøkel. 2023. “Cross-Platform Emotions and Audience Engagement in Social Media Political Campaigning: Comparing Candidates’ Facebook and Instagram Images in the 2020 US Election”. Political Communication 40 (1), 48-68.

Chadwick, Andrew. 2013. The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford University Press.

Dahlgren, Peter. 2009. Media and Political Engagement: Citizens, Communication, and Democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Enli, Gunn Sara, & Eli Skogerbø. 2013. “Personalized campaigns in party-centered politics: Twitter and Facebook as arenas for political communication”. Information, Communication & Society 16 (5), 757–774.

Enli, Gunn Sara. 2017. Mediated authenticity: How the media constructs reality. Peter Lang.

Herkman, Juha. 2008. “Viihdemedian rooli vaaleissa Analyysi vuoden 2006 presidentinvaaleista”. Media & viestintä 31 (4). https://doi.org/10.23983/mv.63008

Herkman, Juha. 2010. “Politiikan julkisuus viestinten välissä: intermediaalisuus ja vaalit”. Media & viestintä 33 (2), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.23983/mv.62936

Herkman, Juha. 2011. Politiikka ja mediajulkisuus. Vastapaino.

Hämäläinen, Karo. 2017. Alex. Otava.

Isotalo, Veikko, Theodora Helimäki, Åsa von Schoultz & Peter Söderlund 2023. Suomalainen äänestäjä 2003–2023/Den finländska väljaren 2003–2023. Vaalitutkimuskonsortio. https://www.vaalitutkimus.fi/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2023-13-Suomalainen-aanestaja-2003%E2%80%932023.pdf

Isotalus, Pekka. 2017. Mediapoliitikko. Gaudeamus.

Kannasto, Elisa. 2025. “Suunnitelmallista huomionkeräämistä ja kokemuspohjaisia valintoja – Poliittisen brändin strateginen viestintä”. In Elisa Juholin & Henrik Rydenfelt (eds.) Strateginen viestintä. ProComma Academic 2025.

Kannasto, Elisa. 2026. [forthcoming]. “Poliitikkojen kampanjaviestintä sosiaalisessa mediassa”. In Josefina Sipinen, Åsa von Schoultz & Elina Kestilä-Kekkonen (eds.) Tie Arkadianmäelle. Eduskuntavaalien 2023 ehdokkaiden resurssit, kampanjointi ja poliittiset arvot. Tampere University Press.

Kannasto, Elisa. 2021. “I am horrified by all kinds of persona worship!”: Constructing personal brands of politicians on Facebook. https://osuva.uwasa.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/13161/978-952-476-983-9.pdf?sequence=2

Kannasto, Elisa & Essi Pöyry. 2025. “Political Campaigning and Social Media Affordances – Mood-setting on TikTok”. Proceedings of the 58th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/109126

Kannasto, Elisa, Laura Paatelainen & Pekka Isotalus. 2023. “Henkilöityminen eduskuntavaalikampanjassa: Puheenjohtajat ja puolueet sosiaalisessa mediassa”. Politiikka 65 (1). https://doi.org/10.37452/politiikka.119455

Karvonen, Erkki. 2009. “Entertainmentization of the European Public Sphere and Politics”. In Jackie Harrison & Bridgette Wessels (eds.) Mediating Europe: New Media, Mass Communications, and the European Public Sphere. Berghahn Books, 99–127. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781845459352-006

Klinger, Ulrike & Jakob Svensson. 2015. “The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach”. New Media & Society 17 (8), 1241–1257.

Laaksonen, Salla-Maaria, Elisa Kannasto & Aleksi Knuutila. 2025. Election campaigns on social media. In Alessandro Nai & Max Grömping (eds.) Encyclopedia of political communication. Edward Elgar.

Lalancette, Mireille & Vincent Raynauld. 2019. “The power of political image: Justin Trudeau, Instagram, and celebrity politics”. American behavioral scientist 63 (7), 888–924. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764217744838

Langer, Ana Inés. 2010. “The politicization of private persona: Exceptional leaders or the new rule?” The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161209351003

Lindholm, Jenny, Tom Carlson & Joachim Högväg. 2021. “See me, like me! Exploring viewers’ visual attention to and trait perceptions of party leaders on Instagram”. The international journal of press/politics 26 (1), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/194016122093723

Marshall, David P, Christopher Moore & Kim Barbour. 2019. Persona studies: an introduction. John Wiley & Sons.

Metz, Manon, Sanne Kruikemeier & Sophie Lecheler. 2020. “Personalization of politics on Facebook: Examining the content and effects of professional, emotional, and private self-personalization”. Information, Communication & Society 23 (10), 1481–1498. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1581244

Nelimarkka, Matti, Salla-Maaria Laaksonen, Mari Tuokko & Tarja Valkonen. 2020. ”Platformed interactions: How social media platforms relate to candidate-constituent interaction during Finnish 2015 election campaigning”. Social Media+ Society 6 (2), 2056305120903856. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120903856

Nieminen, Esko, Elisa Kannasto & Pekka Isotalus. 2022. “Pormestariehdokkaiden imagot sosiaalisessa mediassa”. Focus Localis 50 (3), 46–66. https://cris.tuni.fi/ws/portalfiles/portal/79950085/Pormestariehdokkaiden_imagot_sosiaalisessa_mediassa.pdf

Paatelainen, Laura, Elisa Kannasto & Pekka Isotalus. 2024. “Personalized Politics in Traditional and Social Media: The Case of the 2019 Finnish Parliamentary Elections”. Mediatization Studies 7, 31–48.

Peng, Yilang. 2021. “What makes politicians’ Instagram posts popular? Analyzing social media strategies of candidates and office holders with computer vision”. International Journal of Press/Politics 26 (1), 143–166.

Plazas‐Olmedo, Maite & Pablo López‐Rabadán. 2023. “Selfies and Speeches of a President at War: Volodymyr Zelensky’s Strategy of Spectacularization on Instagram”. Media and Communication 11 (2), 188–202 https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6366

Rapeli, Lauri. 2025. “The Impact of Increased Learning Opportunities on Political Knowledge: Evidence From Repeated Cross-Sectional Surveys in Finland in 2008 and 2020”. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 37 (2), edaf016, https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edaf016

Russmann, Uta, Ulrike Klinger & Karolina Koc-Michalska. 2024. Personal, private, emotional? How political parties use personalization strategies on Facebook in the 2014 and 2019 EP election campaigns. Social Science Computer Review 42 (5), 1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393241254807

Suominen, Jaakko, Sari Östman, Petri Saarikoski & Riikka Turtiainen. 2013. Sosiaalisen median lyhyt historia. Gaudeamus. Helsinki.

Sampietro, Agnese & Sebastián Sánchez-Castillo. 2020. “Building a political image on Instagram: A study of the personal profile of Santiago Abascal (Vox) in 2018”. Communication & society 33 (1), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.33.37241

Street, John. 2012. Politics and Popular Culture. Polity Press.

Szebeni, Zea & Virpi Salojärvi. 2022. “‘Authentically’ Maintaining Populism in Hungary–Visual Analysis of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Instagram”. Mass Communication and Society 25 (6), 812–837. https://doi-org.proxy.uwasa.fi/10.1080/15205436.2022.2111265

Söderlund, Peter. 2023. Äänestäjien liikkuvuus vuosien 2019 ja 2023 eduskuntavaalien välillä | Väljarrörlighet mellan 2019 och 2023 års riksdagsval. FNES, Finnish National Election Study. https://www.vaalitutkimus.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2023-07_Aanestajien_liikkuvuus-Valjarrorlighet.pdf

Tilastokeskus. 2024. Ero ehdokkaiden kannatuksessa 3,2 prosenttiyksikköä presidentinvaalin 2024 toisessa vaalissa. https://stat.fi/julkaisu/cln47u3jbdtqc0bvzmtp7uw1u

Van Aelst, Peter, Tamir Sheafer & James Stanyer. 2012. “The personalization of mediated political communication: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings”. Journalism 3 (2), 203–220.

Van Zoonen, Liesbet. 2005. Entertaining the Citizen: When Politics and Popular Culture Converge. Rowman & Littlefield.

von Schoultz, Åsa & Kim Strandberg. 2024. Political behaviour in contemporary Finland: Studies of voting and campaigning in a candidate-oriented political system. Taylor & Francis.

Yle 16.6.2014. Koivisto, Ilona: “Nykypoliitikko pistää itsensä likoon: Twitter-hai Stubb näyttää suuntaa”. https://yle.fi/a/3-7301255