Drag panic, moral panic, disinformation, lgbtq discrimination, lgbtq rights

Samantha Martinez Ziegler

samazin [a] utu.fi

Doctoral Researcher

Digital Culture, Landscape and Cultural Heritage

University of Turku

How to cite: Martinez Ziegler, Samantha. 2025. ”Hate Is a Drag — Examining the Drag Panic of the 2020s”. WiderScreen 28 (1–2). https://widerscreen.fi/numerot/1-2-2025-widerscreen-28-numerot/hate-is-a-drag-examining-the-drag-panic-of-the-2020s/

Moral panics are built on the disproportional fear of a group of people, things, or behaviours that are falsely perceived to threaten values and norms of society. This irrational fear is fuelled by disinformation and far-reaching narratives that seek to spread panic and call for the hostile and imminent rejection of said “folk devil.” In the 2020s, a sudden drag panic has been spreading worldwide, driven by conservative activists and targeting Drag Story Hour events. By adopting anti-gay narratives and pervasive rhetorics of the past, today’s drag panic demonises LGBTQ people and calls for censorship and the banning of drag performances. This review article provides a wide overview of the art of modern drag, origins of drag panic, and its harmful ramifications. This text was originally written for the 2024 course on Media Criticism and Society as part of the Dark Play -project (“Synkkä leikki”) in the Digital Culture, Cultural Heritage and Landscape program at the University of Turku, and was revisited and last modified in the summer of 2025.

On a Saturday night in November of 2022, a mass shooting took place at Club Q, a Colorado Springs gay bar in Colorado, USA. The shooting resulted in the deaths of five people and over twenty injuries, nineteen caused by gunfire. This attack targeted the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) community, and is an exemplary case of a hate crime of extreme violence towards sexual and gender minorities.

A drag show was hosted at Club Q on the night of the shooting. The following day, the club was scheduled to host a drag musical brunch (New York Times 21.11.2022), a midday family-friendly entertainment event featuring age-appropriate drag performances and a relaxed brunch dining experience. Following the shooting, the expected drag brunch was cancelled. Although the motives behind the attack were first unknown, members of the LGBTQ community, including the co-owners of Club Q, speculated that hosting drag shows might have contributed to the gunman’s decision, fuelled by right-wing anti-drag rhetoric and hatred (Harris 2023, 124; CNN 14.12.2022). Conservative activist Christopher Rufo expressed such sentiments a month prior to the shooting in an article for The City Journal, a conservative policy magazine, particularly framing drag queens and LGBTQ individuals as implicit child groomers (Marwick et al. 2024, 476).

Casualties, injuries, calls for censorship, and further stigmatisation of sexual and gender minorities are some of the direct consequences of the anti-LGBTQ hatred that continues to rise during the 2020s, and more specifically, extremely harmful ramifications of the emergence of drag panic all over the world. This paper examines the central themes surrounding moral panics and introduces a framework to understand the crux of drag panic in the age of modern conservatism and sweeping disinformation.

Moral Panics and the Art of Drag

The term ‘moral panic’ was developed by sociologist Stanley Cohen while working on his PhD in the 1960s, which was the base for his first book entitled Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers (1972). In this work, a moral panic is described as a term to express mass anxiety, fear, or scare over a condition, episode, person, or group of people that is considered a threat to “societal values and interests” (Cohen 2011, 1). From this perspective, moral panics arise when a community perceives their cultural and moral values threatened by an external agent (namely, folk devil), thus creating an intense, oftentimes irrational, widespread feeling of fear amongst its members.

Goode et al. (1994) add to Cohen’s definition of moral panic by stating that “as with all sociological phenomena, threats are culturally and politically constructed, a product of the human imagination” (150–151). On this basis, it would seem that moral panics will always emerge in our society. Although threats to traditional morality and pervasive beliefs can and will be inflated by the media, moral panics are rarely permanent, as panics are in themselves “self-limiting, temporary and spasmodic, a splutter of rage which burns itself out” (Cohen 2011, xxxvii). Yet even though some moral panics are short-lived and do not seem relevant today (e.g., the moral panic over role-playing games such as Dungeons & Dragons during the 1980s), other panics will ultimately have more serious, long-lasting repercussions in society.

On this basis, drag panic is a type of moral panic rooted in the perception of drag being inherently sexual and, thus, harmful to minors. This pervasive rhetoric is primarily used by conservative activists as an ideological disinformation narrative to cause harm to sexual and gender minorities (Marwick et al. 2024, 460). Such rhetoric can be found in the writings of conservative authors like Chrisopher Rufo, who claims that drag is about “reformulating children’s relationship with sex, sexuality, and eroticism” and its goal is “the abolition of restrictions on the behavior at the bottom end of the moral spectrum—pedophilia” (Rufo 2022). In that regard, Harris (2023) considers that drag queens are depicted as a “present-day version of the predatory homosexual,” (156) a recurrent and harmful trope used in anti-LGBTQ movements throughout history, seen in Anita Bryant’s Save Our Children campaign during the 1970s, and previous moral panics, such as the Lavender Scare of the 1950s.

As we delve further into the complexity of drag panic, we must understand what drag is and what is not. Rufo’s claims aside, the art of drag can raise big questions for those unfamiliar to it. Is it just cisgender gay men cross-dressing as women in big wigs, heels, an abundance of make-up, and sequined dresses? Is it lip-syncing in front of a live audience? Is it hyper-sexual, is it tongue-in-cheek and humorous, is it a political statement? Is it ever family-friendly?

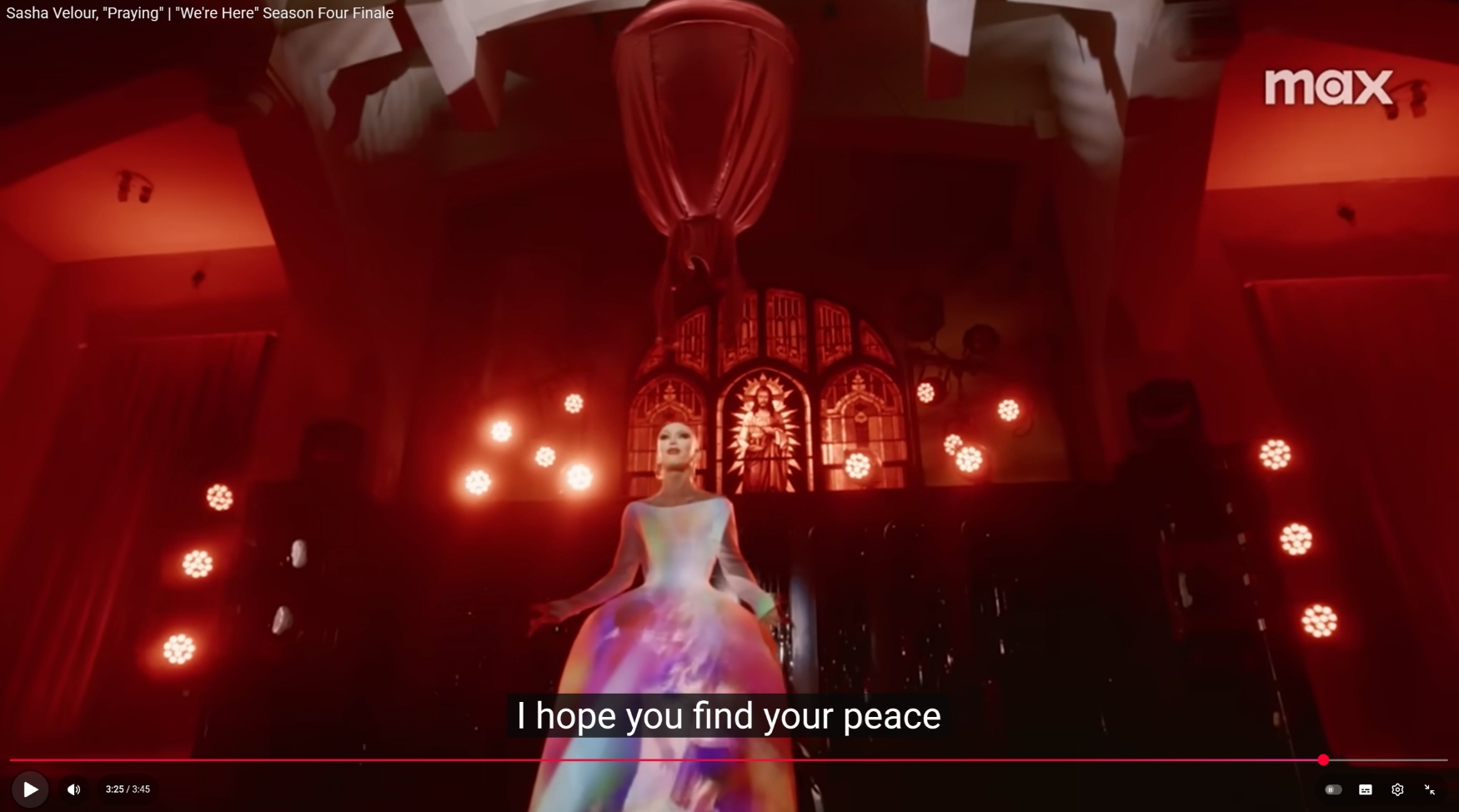

A simple answer for all the questions above is it can be. Drag can be elaborate, drag can be sexual, drag can be goofy. On the other hand, drag can be simple, drag can be family-friendly, drag can be serious. As with any art form, drag encompasses several artistic expressions. In The Big Reveal: An Illustrated Manifesto of Drag (2023), American drag queen and artist Sasha Velour (Alexander Hedges Steinberg, 1987–) explores the history and theory of drag, and addresses the complex question of what drag is based on her research, art, and memoir. Derived from the notion that drag is never exactly one thing but always many things at once (131), Velour asserts that “drag exists in conversation with community, reflecting the world around us and celebrating, stylizing, critiquing, and reinventing it in service of something better” (135).

In academia, drag is understood as an art form where its performers attempt to present “new, altered, transgressive, or, most importantly, parodic gender identities within the context of performance” (Moore 2013, 17). Drag performers adopt a drag persona through which to portray an exaggerated gender expression; those who exaggerate femininity are known as drag queens, while their masculine counterparts are known as drag kings. These drag personas portrayed by the performers include names and mannerism that make the presentation of their characters unique and recognisable. Although drag has been closely linked to cross-dressing, modern drag proves to be more complex than that (Moore 2013, 18–19). By playing with elements of femininity and masculinity in their performances, drag queens and kings show “multiple ways to practice and experience gender” (Berkowitz & Belgrave 2010, 161–162), by displaying “humour, wit, and comedy for the audience” (Campana et al. 2022, 1967). Overall, drag is a performance art, a creative, staged, and imaginative type of entertainment that explores and often challenges traditional gender norms.

Generally, drag performers are part of sexual, gender, and racial minorities. As Velour (2023) explains, drag performance is part of queer history because it is the LGBTQ community “who has fought the hardest to protect this art” (7). Harris (2023) supports this notion, asserting that drag “serves as an important connection to LGBTQ culture” (129). Our understanding of modern drag has its roots in the late 19th century in the US, and can be traced back to African-American activist and formerly enslaved man William Dorsey Swann (1858–1923), a gay black man who hosted private parties or balls in his home called drags, “where he would perform in elegant feminine attire” and “were mostly attended by fellow formerly enslaved people” (GLAD Law 2023).

Racial minorities, particularly African Americans and Latinos, have been involved in the evolution of modern drag culture. Strong drag communities bloomed in the New York ballroom scene of the 1980s, a subculture mostly made up of marginalised queer people of colour (Fitzgerald & Marquez 2020, 33). The origin of a collection of cultural expressions and traditions in modern drag that are now part of a larger cultural mainstream, such as vogueing or the art of shade, can be traced back to the ballroom scene. Likewise, ballroom culture redefined the terminology around drag (Velour 2023, 23). With this in mind, modern drag allows and celebrates elements of queerness, gender, and ethnicity to circulate freely and often overlap.

Drag is a skilled artistic expression no different from a staged theatrical performance. It is within this context that the core questions of this review article emerge: why is there a growing anti-drag movement right now? How did it come to be? And, more importantly, how did this movement become such a widespread moral panic?

Drag Story Hour

It has previously been established that the current drag panic is largely caused by viewing drag as an inherently sexual performance that is not suited for children. Although drag queens are now being targeted by this rhetoric, the demonisation of LGBTQ people in regard to children is anything but new. In the comparative study Child-Sacrificing Drag Queens (2024), Marwick et al. explore the history of harmful narratives used by anti-LGBTQ movements in the past and present. They establish that throughout history, expressions of queerness have been perceived as a folk devil, as to be queer “is to be a moral threat to heteronormativity” (Marwick et al. 2024, 460).

In this vein, the marginalisation and stigmatisation of LGBTQ people throughout history has highly affected how drag is perceived. For example, queer people were subject to prosecution through several laws during the late 19th and 20th centuries, many of which criminalised acts like sodomy and cross-dressing (Harris 2023, 154–155). It is particularly the breaking of societal norms surrounding gender and sexual orientation and expression that has led to the stigmatisation of drag in the past (Campana et al. 2022, 1951). At its core, today’s drag panic is not too different.

From 2020 onwards, one of the perceived threats within the context of drag panic has been Drag Story Hour[1] (DSH). The umbrella term is used to describe children’s literacy and artistic events to promote reading, diversity, and tolerance which are hosted by drag performers in public libraries, schools, and bookstores. As of June 8, 2025, the goals of DSH described in their official website are to work towards “a future where all people learn via LGBTQIA+ storytelling to embrace themselves and champion free expression in their communities” (Drag Story Hour 2025). The DSH initiative originated in San Francisco in 2015, but has since expanded across North America, Europe, and Australia, having over 50 chapters worldwide (Ellis 2022, 95). Starting as drag queens reading to children, DSH has now expanded into implementing larger literary and creative programs for children.

The War on DSH: A Global Movement

The growing popularity and visibility of these events have made them extremely controversial and a target of anti-drag and anti-LGBTQ activism. Public libraries have particularly been attacked by this growing movement. For example, in Sweden, some public libraries scheduled to host DSH events in the autumn of 2022 were the target of heated debates, despite DSH’s goals of inclusion and acceptance aligning “with the objectives of Swedish cultural policy and library regulations” (Engström 2024, 239). The correlation between this conflict and the spread of drag panic in the year 2022 is not coincidental. Although conservatives have been pushing for the ban of LGBTQ literature in schools and public libraries as they deem it inappropriate for minors, the current war on DSH stands out among other forms of LGBTQ censorship as “its main target is not specific book titles nor specific speakers, but the method in which stories are presented to children” (Ellis 2022, 95). That is to say, the pressing issue is not the material read at DSH, but the manner in which it’s read.

The pushback against DSH is not a mere matter of public and social media debate. Numerous protests have been held outside venues scheduled to host DSH events all around the globe. For example, among the hundreds of anti-LGBTQ demonstrations that took place in 2022 and 2023 in the US, over 161 protests and threats specifically targeted drag events and DSH (GLAAD 2023).

In Finland, a group of anti-drag activists gathered outside of the Helsinki Central Library Oodi in 2022 to protest against satutuokio belonging to Helsinki Pride, hosted by Finnish drag queen Gaylien 2000 (Yle 1.7.2023). After around 20 protesters were removed by police, the event was able to take place in the public library (Figure 2 & 3). While these kinds of non-violent protests have taken place in Finland, other countries have seen stronger negative reactions, including harassment and intimidation both online and in person, assault, and property damage (Ellis 2022, 95). As opposed to the message of inclusion and literacy that DSH works towards, the one sent by protesters is one of intolerance, prejudice, and discrimination.

In the report A Year of Hate: Understanding Threats and Harassment Targeting Drag Shows and the LGBTQ+ Community (Squirrel & Davey 2023), the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) reviews the growth of the anti-LGBTQ movement in the Americas, Europe, and Australia in 2022. More specifically, in this document, the ISD focuses on the current anti-drag activism by examining over 200 anti-drag mobilisations at a global scale.

The report identifies the US as the main anti-drag actor in the anti-LGBTQ movement, with the largest number of anti-drag protests and the highest number of violence attributed to the cause (Squirrel & Davey 2023, 5). While the previously discussed Colorado Springs shooting is an act of extreme violence towards the LGBTQ community and drag performers, other acts of violence include vandalism, doxxing, violent threats, and harassment towards performers and venues that host drag events both in person and online (Squirrel & Davey 2023, 11). Furthermore, many US states have been trying to pass new anti-drag legislation since 2023, especially in Western states like Oklahoma and within the Bible Belt, like Tennessee and Florida (NBC News 1.6.2023). The proposal and passing of regulations and legislations is also a consequence of moral panics (Goode et al. 1994, 168–169). By vocally condemning drag through organised demonstration, protesters call for the banning of Drag Story Hour and censorship of LGBTQ materials in public libraries and schools.

As already noted, the biggest narrative surrounding the current drag panic is the framing of drag as inherently being harmful to children, shielding behind the narrative of drag being an inherent sexualised performance. Anti-drag activists often justify their actions under the excuse of “protecting children” (Squirrel & Davey 2023, 12). In other words, even if political actions become violent or directly harm drag performers, anti-drag advocates consider them a rightful response against a growing threat against morality: drag. As noted by Goode et al. (1994), hostility is one of the biggest characteristics of moral panics, following concern (156-159). When a moral panic emerges, there is an increased and expected level of hostility and violence towards groups of people who engage in the alleged threatening behaviour. Therein surges the mentality of us, the morally correct people, versus them, those who oppose a threat to our values and, therefore, are evil (Goode et al. 1994, 157). Drag panic follows the same dichotomy: anti-drag activists view themselves as the good in the fight, a folk hero battling the villain, drag, a folk devil standing against societal values.

News and Disinformation: The Driving Force Behind Modern Moral Panics?

Cohen (2011) maintains that news is often the main source of information “about the normative contours of a society” (11). In other words, the news plays a big role in framing narratives of right and wrong, of correctness and deviance to large audiences. News networks are responsible to feed information to news consumers, and when this information is tailored to fit the ideological preferences of a specific audience, the already existing bias against groups of people can be strengthened.

Take the American news channel Fox News as an example. Fox News is known to have a bias towards the Republican Party and against the Democratic party, as it presents information from a conservative standpoint and, as a result, a strong link is established between broadcaster and the political affiliation of its consumers (Hoewe et al. 2021, 368). Fox News has, for instance, been an active agent in framing conservative narratives around immigration in America. [2] The framing of immigration as invasion by Fox News portrays Latin American immigrants as a threat, thus further dehumanising and stigmatising Hispanic immigrants (Hoewe et al. 2021, 382). With American president Donald Trump regularly employing anti-immigration rhetoric in rallies during his 2024 presidential campaign (e.g., stating that immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country,” [Reuters 17.12.2023]), and reports of over 70 % of Republicans wanting immigration decreased in the country (Gallup 13.7.2023), Fox News becomes an echo chamber for its conservative viewers.

In a similar manner, conservative news networks like Fox News are active actors in the anti-drag and anti-LGBTQ movement of today. The rhetoric used by conservative news networks converge into a “collective narrative structure” driven by conspiracy theories and “targeted disinformation campaigns” (Marwick et al. 2024, 475). A 2023 study by American non-governmental LGBTQ advocacy organisation Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) found that multiple drag shows were first targeted by news outlets like Fox News and the Daily Wire prior to in-person anti-drag demonstrations taking place. The report explains that these conservative news networks would misinterpret upcoming drag shows, “spinning them as harmful to children, and protests or threats would follow” (GLAAD 2023). This, undoubtedly, factors in the growth and spread of drag panic in the US and its global dissemination through conservative social media channels.

Harris (2023) expands on the topic by explaining that these conservative news outlets and social media channels further the anti-drag sentiment by pushing the narrative that “drag performers are corrupting the minds of children with gender ideology, grooming and sexualizing children, and, overall, corrupting our society’s moral compass” (154). In doing so, the group of society that is constantly fed this biased and false information begins to believe such a threat is real. Goode et al. (1994) describe this widespread agreement (consensus) as another key characteristic of moral panics (156–159). However, it is important to note that although moral panics see members of a society reaching general agreement regarding a supposed emergent threat, this percentage of the population do not need to make the majority (Goode et al. 157). That is to say, moral panics can cause great fear and concern in certain groups of our society; sometimes these groups make the majority, and sometimes they do not.

Drag Culture in the Mainstream

As I have stated throughout the text, Drag Story Hour finds itself at the centre of the drag panic of the 2020s. Its mere existence threatens the value of conservatives who believe these events can be harmful to kids, be it because of narratives that frame drag as a sexualised performance, or because the goals of DSH include advocating for inclusion and acceptance of LGBTQ people. At the same time, although the Drag Story Hour project began in 2015, drag panic has spread and grown stronger in the 2020s. A factor that may influence the current focus on drag is the introduction of drag culture into the mainstream media.

Today, drag has become a larger cultural phenomenon, gaining growing and steady visibility during the 2010s than in decades prior (Ellis 2022, 107). From television series, to music, film, and social media, drag has made its presence felt during the past decade. Harris (2023) credits American drag queen RuPaul Charles as one of the biggest contributors of drag in mainstream society (133). In this respect, the American reality competition television series RuPaul’s Drag Race (RPDR [Logo, VH1, MTV 2009 –]) particularly stands out.

With over sixteen seasons, spin-offs, as well as numerous international adaptations, and plenty Emmys and accolades, Drag Race is responsible for bringing drag culture to a large audience all across the world (Martinez Ziegler 2024). The premise of the original RPDR series is to have a group of drag queens competing in several challenges to earn the title of America’s Next Drag Superstar and a cash prize of $200,000. Contestants, also known as racers, get to showcase their skills in makeup, dance, comedy, and overall drag performance throughout the entire competition, while RuPaul acts as the host and main judge of the show.

Modern television, particularly in the case of reality television, is highly affective: it aims to provoke, challenge, and generate emotions in the viewer (Tuomi 2019, 48). Although it varies from program to program, this is often achieved by amplifying the “spontaneous” situations captured by the camera. At the same time, television can become a medium where to open dialogue about topics that are often viewed as taboo (Tuomi 2019, 54; Tuomi, 2022). All of these elements are present in RPDR. Whether it is through scripted conflicts between two or more contestants and encouraging the viewer to take a side, or by bringing hurtful queer pasts and experiences under spotlight by discussing the marginalisation of sexual and gender minorities in the show, RPDR aims to keep the audience engaged by generating reactions with every episode. In doing so, the show further encourages its audience to question what genuine solidarity is, and what political causes are worth fighting for (Hermes 2023, 142).

For example, Tuomi (2019) explains that confession cam segments are used in reality TV to show a person’s personality, emotions, and thoughts to the viewer (67). These reflective segments are a big part of RPDR. Each episode includes confession cam segments throughout the entire episode, where contestants are shown out of drag (i.e., as the “real” queer people behind the drag persona). Brennan & Gudelunas (2017) stress the importance of these segments for the narrative of the show, explaining that it is through them that the audience gets to know how their queer identities are formed “by experiences of pain, abandonment, rejection and abuse, as well as those of love, partnership, re-connection and support” (31). In other words, RPDR does not only bring drag performances into the mainstream, but queer experiences as well.

From the late 2010s onwards, the overall success of the Drag Race franchise extends beyond television, with former contestants “taking over YouTube and Instagram, and getting Netflix specials” after their appearances on the show (Harris 2023, 133–134). Case in point, American drag queen Trixie Mattel (Brian Firkus, 1989–) has become one of the most well-known drag queens in the world, gaining a lot of fame after her appearance in the seventh season of the show and winning the third instalment of the spin-off series RuPaul’s Drag Race: All Stars in 2018. Apart from being known for her high-camp style of drag and comedy, Trixie has built a multimedia empire consisting of her own make-up line, Trixie Cosmetics, four music albums, international tours, several web series including Netflix’s I Like to Watch (2019–), and a motel, which renovation was covered in Discovery’s docuseries Trixie Motel (2022–), to name a few. Several drag performers have followed similar paths after their Drag Race career and have thus played a role in making the presence of drag felt in our everyday lives.

Although the introduction of drag culture into the mainstream creates many positive outcomes, especially in the context of destigmatising the lives and experiences of sexual and gender minorities, it also turns drag performers into targets of hate crimes (The Washington Post 21.8.2022). Drag is more visible than ever before, more accessible; it does not only occur in underground clubs and hidden venues as it once did. Drag can be spotted in popular media, at local bookstores and libraries, and even in the makeup aisle at the department store. It is this prevailing presence in our society that is perceived as a threat and challenge to conservative values, which is where drag panic truly stems from; a newfound active threat to the morals of society that is “uncontrollable, unknowable, unfamiliar” (Goode et al. 1994, 163).

Conclusion

As I have been examining throughout my text, Drag Story Hour has found itself at the very centre of drag panic during the past couple of years. The hundreds of protests and threats that have emerged in the 2020s have targeted drag performers, public venues where DSH is held, and the very values and objectives of the program. However, the false narratives adopted by conservative groups and anti-drag activists echo intolerant and homophobic remarks that have been utilised in anti-LGBTQ movements throughout history.

Goode et al. (1994) suggest that moral panics can be built upon older ones (169). The grooming narrative implemented by anti-drag activists is part of a much older anti-LGBTQ rhetoric, which can be found, for instance, in Anita Bryant’s 1977 Save Our Children campaign, the first organised opposition to LGBTQ rights in the US that aimed to keep gay people out of public and social life (The Washington Post 24.7.2023). In fact, Harris (2023) considers that the greater anti-LGBTQ movement of today mirrors the late 19th century’s “concerns around gender and sexual deviation” (154–155). Because queer lives challenge heteronormative norms, panics that surround them view their existence as a threatening behaviour.

To summarise, the anxieties and disproportional fear that drive drag panic are not new. They are built upon already existing anti-LGBTQ sentiments and narratives that demonise gender and sexual minorities. The visibility of drag culture in today’s society thanks to its introduction into the mainstream, as well as the push towards tolerance and acceptance of gender and sexual minorities during the past decade mark a key difference in the moral panic of today. Within this framework, I argue that this perceived modern “openness” has been translated into a growing and imminent threat to traditional values by conservative thinkers, fuelled by disinformation and conspiracy theories. In true moral panic fashion, the consequences of the modern drag panic are acts of extreme violence, discrimination, and criminalisation of drag. The pendulum swings, and its current trajectory seems to be towards intolerance.

“There are windows of openness in our culture. And then our culture closes those windows down just as fast. (…) In a culture, you can choose fear or love. It’s been my experience and my observation that humans on this planet feel more comfortable with fear rather than love and openness. So, the future of drag? Who knows what it is. I do know what history tells us about humans. And humans, they actually don’t feel very comfortable with openness and freedom. They really don’t.”

RuPaul Charles (Metro Weekly 7.4.2016)

References

All links verified 9.6.2025.

Figures

Figure 1

BBC News 19.06.2023. ”Stockholm’s deputy mayor hosts drag queen story hour”. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0fw1d9n

Figure 2

Kansalainen 1.7.2022. Nina Metsälä: ”Helsingin keskustakirjasto Oodin edessä pidettiin 1.7. mielenosoitus pikkulasten groomausta vastaan”. https://www.kansalainen.fi/helsingin-keskustakirjasto-oodin-edessa-pidettiin-1-7-mielenosoitus-pikkulasten-groomausta-vastaan

Figure 3

Keskustakirjasto Oodi 2022. ”Kiitos herttaiselle Gaylien 2000 -alienille. Facebook. July 1, 2022. https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=5681998721813072

Figure 4

Women & the American Story (WAMS). n.d. Anti LGBTQ+ Activism. Resource. https://wams.nyhistory.org/end-of-the-twentieth-century/the-information-age/anti-lgbtq-activism/

SASKTODAY.ca. 16.10.2022. Jon Perez ”Protesters, LGBTQ supporters clash over children’s storytelling event”. https://www.sasktoday.ca/central/local-news/protesters-lgbtq-supporters-clash-over-childrens-storytelling-event-5964535

Figure 5

Deadline 16.08.2024. Armando Tinoco: ”‘RuPaul’s Drag Race’ Renewed For Season 17 At MTV; Paramount+ Picks Up ‘RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars’ For Season 10”. https://deadline.com/2024/08/rupauls-drag-race-season-17-mtv-all-stars-season-10-paramount-plus-1236041806/

Figure 6

Trixie Cosmetics 2024. ”The million dollar question.” Facebook. August 26, 2024. https://www.facebook.com/TrixieCosmetics1/posts/pfbid02a4PGcRhVPfK2pQKna7DjtVNkUstentf3EdzsbUpjFFpxZ61hKYCPUdRUVsperXxJl

The Fashion Doll Chronicles 13.11.2021. ”Integrity Toys makes a Mattel! Trixie Mattel!”. https://fashiondollchronicles.com/fashiondollchronicles/2021/11/13/integrity-toys-makes-a-mattel-trixie-mattel

Trixie Mattel. n.d. ”Icon, Legend & Star”. Linktree. https://linktr.ee/trixiemattel

Literature

Berkowitz, Dana & Linda Liska Belgrave. 2010. ““She Works Hard for the Money”: Drag Queens and the Management of Their Contradictory Status of Celebrity and Marginality.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 39 (2), 159–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241609342193

Brennan, Niall & David Gudelunas. 2023. Drag in the Global Digital Public Sphere: Queer Visibility, Online Discourse and Political Change. Routledge Research in Cultural and Media Studies. Routledge.

Campana, Mario, Katherine Duffy & Maria Rita Micheli. 2022. ““We’re All Born Naked and the Rest Is Drag”: Spectacularization of Core Stigma in RuPaul ’s Drag Race.” Journal of Management Studies 59 (8), 1950–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12848

CNN 14.12.2022. Sarah Fortinsky: “‘Shame on you’: Club Q survivors blame GOP rhetoric for mass violence”. https://www.cnn.com/2022/12/14/politics/club-q-survivors-hearing

Cohen, Stanley. 2011. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers. Routledge Classics. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge.

Ellis, Justin R. 2022. “A Fairy Tale Gone Wrong: Social Media, Recursive Hate and the Politicisation of Drag Queen Storytime.” The Journal of Criminal Law 86 (2), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220183221086455

Engström, Lisa, Hanna Carlsson & Fredrik Hanell. 2024. “Drag Story Hour at Public Libraries: The Reading Child and the Construction of Fear and Othering in Swedish Cultural Policy Debate.” Journal of Documentation 80 (7), 226–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2024-0026

Fitzgerald, Tom & Lorenzo Marquez. 2020. Legendary Children: The First Decade of RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Last Century of Queer Life. New York: Penguin Books.

Gallup 13.7.2023. Lydia Saad: “Americans Still Value Immigration, but Have Concerns”. https://news.gallup.com/poll/508520/americans-value-immigration-concerns.aspx

GLAAD. 2023. “UPDATED Report: Drag Events Faced More than 160 Protests and Significant Threats Since Early 2022.” GLAAD. https://glaad.org/anti-drag-report

Glad Law. 2023. ”International Drag Day: Drag and the Fight for LGBTQ+ Rights.” Glad Law: GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders. July 16, 2024. https://www.gladlaw.org/international-drag-day-drag-and-the-fight-for-lgbtq-rights/

Goode, Erich & Nachman Ben-Yehuda. 1994. “Moral Panics: Culture, Politics, and Social Construction.” Annual Review of Sociology 20 (1), 149–71. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.20.080194.001053

Harris, Zackary W. 2023. “Shantay You Stay: Keeping Kids at Drag Shows.” Journal of Law and Policy 32 (1). https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/jlp/vol32/iss1/4

Hermes, Joke. 2023. Cultural Citizenship and Popular Culture: The Art of Listening. 1st ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003288855

Hoewe, Jennifer, Kathryn Cramer Brownell & Eric C. Wiemer. 2021. “The Role and Impact of Fox News.” The Forum 18 (3), 367–88. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2020-2014

Martinez Ziegler, Samantha. 2024. “’History? No, Henny, This is HERstory’ — Queer History as Entertainment in RuPaul’s Drag Race”. WiderScreen 27 (1–2). https://widerscreen.fi/numerot/1-2-2024-widerscreen-27/history-no-henny-this-is-herstory–queer-history-as-entertainment-in-rupauls-drag-race/

Marwick, Alice, Jacob Smith, Belle Basnight, Dahlia Boyles, Margaret Donnelly, Stephanie Kaczynski, Evan Ringel, Sarah Whitmarsh & Carolina Yabase. 2024. “Child-Sacrificing Drag Queens: Historical Antecedents in Disinformative Narratives Supporting the Drag Queen Story Hour Moral Panic.” Women’s Studies in Communication 47 (4), 459–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2024.2396288

Metro Weekly 7.4.2016. Dough Rule: “RuPaul: Ultimate Queen”. https://www.metroweekly.com/2016/04/ultimate-queen-rupaul/

Moore, Ramey. 2013. “Everything Else Is Drag: Linguistic Drag and Gender Parody on RuPaul’s Drag Race.” Journal of Research in Gender Studies 3 (2), 15–26.

NBC News 1.6.2023. Elaina Patton, Jillian Eugenios, Ellie Rudy, Brooke Sopelsa & Jay Valle: “Pride 30: Drag performers who made ’herstory’”. https://www.nbcnews.com/specials/pride-month-2023-drag-performers-who-made-herstory/index.html

New York Times 21.11.2022. Michelle Goldberg: “Club Q and the Demonization of Drag Queens”. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/21/opinion/colorado-springs-shooting.html

Reuters 17.12.2023. Nathan Layne: “Trump repeats ’poisoning the blood’ anti-immigrant remark”. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-repeats-poisoning-blood-anti-immigrant-remark-2023-12-16/

Rufo, Christopher. 2022. “The Real Story Behind Drag Queen Story Hour.” The City Journal. October 23, 2022. https://www.city-journal.org/article/the-real-story-behind-drag-queen-story-hour

Squirrell, Tim & Jacob Davey. 2023. A Year of Hate: Understanding Threats and Harassment Targeting Drag Shows and the LGBTQ+ Community. London: Institute for Strategic Dialogue. https://www.isdglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Understanding-Threats-and-Harassment-Targeting-Drag-Shows-and-the-LGBTQ-Community.pdf

Tuomi, Pauliina. 2019. “Pakko Katsoa?! Nykypäivän Provokatiivinen Televisiotuotanto Mediateollisuuden Muotona”. Lähikuva 31 (4), 48–79. https://doi.org/10.23994/lk.77933

Tuomi, Pauliina. 2022. “Puhtoisuuden illuusio: moraali- ja arvokäsityksiä ravistelevat televisiotuotannot mediassa”. WiderScreen 25 (1–2). http://widerscreen.fi/numerot/2022-1-2/puhtoisuuden-illuusio-moraali-ja-arvokasityksia-ravistelevat-televisiotuotannot-mediassa/

Velour, Sasha. 2023. The Big Reveal: An Illustrated Manifesto of Drag. Harper.

The Washington Post 24.7.2023. Susanna Cassisa: “The ‘groomer’ anti-LGBTQ+ panic is not new — and has caused immense harm“. https://www.washingtonpost.com/made-by-history/2023/07/24/groomer-lgbtq-germany-children/

The Washington Post 21.8.2022. James Bikales: “Drag faces new threats as it moves into the mainstream“. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/08/12/drag-mainstream-attacks-crossroads/

Yle 1.7.2023. Rosa Lehtokari & Tiina Karppi: “Poliisi poisti häiriköijiä Oodista, jossa oli menossa drag queenin pitämä lasten satutunti – kirjastonjohtaja: mielenosoittajilla näkyi hakaristejä”. https://yle.fi/a/3-12519192

Notes

[1] Also known as Drag Queen Story Hour, Drag Queen Storytime, and Drag Story Time.

[2] For more information on this, see Understanding Trump Supporters’ News Use: Beyond the Fox News Bubble (2021), Sadie Dempsey et al.; Media: Fox News, Racism, and White America in the Age of Trump (2021), Kalemba Kizito; Media Coverage of LGBT Issues: Legal, Religious, and Political Frames (2019), Scott N. Nolan.