mobile phones, personalization, customization, digital culture

Markku Reunanen

markku.reunanen [a] aalto.fi

Senior university lecturer, Aalto University

Docent, University of Turku

Adela Lujza Lučenič

lujza.lucenicova [a] aalto.fi

MA student, Aalto University

Petra Noppari

petra.noppari [a] aalto.fi

MA student, Aalto University

MSc student, Tampere University

Lu Chen

lu.1.chen [a] aalto.fi

MA student, Aalto University

How to cite: Reunanen, Markku, Adela Lujza Lučenič, Petra Noppari & Lu Chen. 2025. ”External, Integrated and Digital Personalization: How the Mobile Phone Became Unique”. WiderScreen Ajankohtaista. https://widerscreen.fi/numerot/ajankohtaista/external-integrated-and-digital-personalization-how-the-mobile-phone-became-unique/

This article examines the development of mobile phone personalization from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, focusing on three key categories: external, integrated and digital personalization. As mobile phones evolved from utilitarian devices to personal accessories, a wide range of stakeholders introduced options for consumers to personalize their devices. Phone cases, colorful covers, ringtones and operator logos gave birth to a complete industry supporting such customization. Drawing on two main sources, contemporary magazines and newspapers, and unforeseen material from the recently opened Nokia Design Archive, we use Madeleine Akrich’s concepts of script and projected user to analyze how these stakeholders shaped mobile phone personalization. More than surface-level decoration, such modifications became a key mechanism for technology adoption, individual distinction and cultural integration of mobile technology at the turn of the millennium, reflecting shifts in consumer identity, design practices and the emerging mobile media culture.

Introduction

The 1990s were a decade of rapid growth for the mobile phone industry. Even if existing technologies, such as the Nordic NMT and American AMPS, had already earlier facilitated car and hand-held phones, it was over the 1990s that the mobile phone became affordable and personal, when companies started increasingly targeting the mass market (e.g. Häikiö 2001, 17, 178). In addition to technical development, the shift required effort for changing the mobile phone’s professional – even yuppie – image into something that would appeal to wider audiences (e.g. Haddon 1997; Pantzar 2000, 109–11). One factor that went firmly hand in hand with such efforts was personalization, which manifested itself in a number of ways ranging from colorful covers to ringtones and so-called operator logos.

In this article, we chart the kinds of personalization options that were available to customers in the 1990s and early 2000s, the roots of such options, and the stakeholders involved in providing and facilitating them. Another closely related term, customization, can be thought to include personalization, but also technical features, such as supported networks, storage size, memory capacity and camera specifications, which are not uniform across markets even if the base device is (e.g. Comstock, Johansen & Winroth 2004; Choe, Liao & Sun 2012). The framing here could be defined as Nokia and Finland first, with comparisons to others, as the company was the market leader since 1998 (Häikiö 2001, 177) and, arguably, also the design leader of the time, who introduced or popularized several personalization features. Distilled into two research questions:

- How did mobile phone personalization emerge, evolve and become integrated into consumer culture during the late 1990s and early 2000s?

- What roles did different stakeholders play in shaping this process?

Domestication (Silverstone, Hirsch & Morley 1992) and diffusion of innovations (Rogers 1962) are two common theories that have been applied to early mobile phone adoption (e.g. Haddon 1997; Jaakkola, Gabbouj & Neuvo 1998; Leung & Wei 1999; Lehtonen 2003; Koskinen & Kurvinen 2005). As per its name, domestication deals with the domestic sphere, which only partially matches the use cases of a mobile phone (see Silverstone 2006). All in all, a general model of technology adoption is not particularly useful when focusing on devices’ low-level features. Diffusion is a somewhat better candidate with its innovation-decision process model and adopter categories, but not a direct match either, as our focus is not on the spread of technology in social networks.

Madeleine Akrich’s (1992) concepts of script and projected user are a better fit for the general analysis here because of our interest in designers’ expectations about users’ tastes, skills, needs and motivations. Furthermore, when creating personalization options, designers envision ways of how they will be used, or in other words they script the technological object. Akrich’s work is an extension of Actor-network theory and, therefore, naturally lends itself to the study of a diverse network of actors – be they people, institutions or technologies. As we will demonstrate, early mobile phone personalization, too, came to be because of the interactions within such a network.

The main bodies of research material for this article are newspaper and magazine articles, advertisements and the diverse materials found in the Nokia Design Archive. Most of the articles and advertisements were selected from the Finnish Iltalehti tabloid, as it was in wide circulation and represents what the general public saw at the time, not just special audiences. The search started with phone model names and the personalization options we could initially think of, expanded as we discovered more, and finished with 74 items when no new content appeared. As personalization is linked to fashion and trends, some additional searches to Vogue and Vanity Fair provided extra data on how phone companies tried to reach such audiences. The online Mobile Phone Museum (n.d.) was used for finding technical specifications and publication years of phone models.

The Nokia Design Archive (2025) is a collection of the company’s documents and artifacts generated during their design processes. These materials were donated to Aalto University by Microsoft Mobile oy and designers when the company ceased its phone production business around 2016. For this research, the archive provided unique phone manufacturer’s perspectives with formerly confidential materials, such as concept presentations, sketches, and design research documents. All selected materials – 38 items from Iltalehti, 14 from Vogue, 4 from Vanity Fair and 13 from the Nokia Design Archive – were subjected to a close reading of both their textual and visual content to unearth details, such as stakeholders, argumentation, proposed target audiences and properties of personalization options (see Brummett 2009).

After the introduction, we proceed to related work and provide an overview of how other researchers have studied mobile phone customization and personalization, followed by discussion on how fashion and trends shaped the device. Next follows an overview of our tripartite typology of personalization, utilized in the following three sections where we provide examples of each category, coupled with discussion on their development before the smartphone age and the stakeholders involved. Finally, we provide some general conclusions concerning mobile phone personalization and its evolution.

From a Tool to a Commodity

Mobile phone personalization has evolved in response to both technological improvements and shifting market demands. From the 1980s to the mid-1990s, mobile phones were generally bulky and uniform, with a focus on basic functionality and connectivity for serving mainly business clients (e.g. Haddon 1997). An important evolutionary step was taken with the introduction of the GSM standard, first deployed in Finland in 1991, which enhanced network efficiency, compatibility and scalability, making mobile phones increasingly accessible to the general public. So-called feature phones were introduced in the early 2000s, along with multimedia capabilities, like MP3 players, FM radios, customizable ringtones, wallpapers and alarm sounds. A new stakeholder group became prominent as teleoperators began targeting a growing consumer market by offering mass customization options for their products (Choe, Liao & Sun 2012).

In their article, Choe, Liao and Sun (2012) discuss the challenges manufacturers faced when prioritizing mass customization possibilities for the rapidly expanding consumer market at the time. According to their definition, mass customization is the strategic middle ground that aims to balance mass manufacturing and standardization with the manufacturer’s predetermined customization possibilities. They underline that the mass customization of mobile phones includes both hardware and software modifications. Personalization, according to them, occurs after purchase and is driven by the consumer rather than the manufacturer. It is more individualized and frequently focuses on the interface and user experience rather than physical features. (ibid.) User experience here refers to how users engage with mobile phone customization features, the sense of joy and emotional connection they feel while personalizing their devices, and the overall convenience and intuitiveness of using those customization options.

Whereas Choe, Liao and Sun’s (2012) paper acts as a practical link between theoretical understanding and industrial application by conducting empirical research on which customization features provide the most value, Blom and Monk (2003), and Häkkilä and Chatfield (2006) seek to understand the customer motives that drive why and how users modify their devices. According to their research, users tweak their devices not just to improve their appearance, but also to represent their individuality, provide an improved user-friendly experience, and form emotional ties with their technology. Blom and Monk’s (2003) theoretical study, and Häkkilä and Chatfield’s (2006) empirical case study conclude that users gradually customize their gadgets over time, adjust settings to different social contexts, and are motivated by both functional benefits and personal expression.

Comstock, Johansen and Winroth (2004) summarize the transitions of the Swedish mobile phone industry and how companies may develop the ability to deliver customization at scale. According to their findings, significant improvements in both organizational procedures and supply chain interactions were required to facilitate mass customization, as well as closer integration of design, manufacturing and distribution systems. While Comstock, Johansen and Winroth (2004) present industrial perspectives on how manufacturers can provide mass customization options, Choe, Liao and Sun (2012) detail the types of customization options users prefer, Häkkilä and Chatfield (2006) present a case study on user customization practices, and Blom and Monk (2003) evaluate the psychological reasons why users want to customize and personalize their devices. Customization is a multifaceted trend that requires not only industrial expertise but also an understanding of consumer preferences, habits and underlying reasons for personalization. To use Akrich’s (1992) terminology, the expectations concerning the projected user are turned into a script embedded in the device itself and its surrounding material, such as advertisements and user manuals.

In turn, Bar, Weber and Pisani (2016) examine how users appropriate mobile technologies by actively integrating them into their social, economic and political life. They argue that appropriation is a creative and political process involving negotiation over technology’s use, configuration and benefits. Drawing on metaphors of baroquization, creolization and cannibalism, the authors link modern appropriation to historical cultural exchanges in Latin America, illustrating how people adapt, blend and modify technologies rather than passively adopt them. The article stresses that understanding these processes is important for assessing mobile technology’s broader impacts and advocates viewing users as active creators who drive innovation through experimentation and adaptation.

Lara Srivastava’s (2005) and Leopoldina Fortunati’s (2013) publications extend the works of Blom and Monk (2003), and Häkkilä and Chatfield (2006), but from distinct disciplinary perspectives: social behavior, cultural aesthetics and fashion theory. In their pre-smartphone era article, Srivastava (2005) argues that mobile phones have fundamentally altered social behavior and interaction, blurring the lines between public and private places (see also Silverstone 2006). According to Srivastava (2005), customization is a type of social signaling that enhances the user’s own identity and self-presentation. In turn, Fortunati (2013) views the mobile phone customization trend as part of a larger fashion and design culture: in their view, mobile phones are fashion objects that serve broader roles in creating visual identities and symbolic values for their users. Both authors believe that mobile phone customization serves as an extension of personal identity and that, in general, mobile phones are cultural objects that go beyond their straightforward technological utility (Srivastava 2005; Fortunati 2013).

Chen and Chen (2016) evaluated how users modify their mobile phones in everyday life, concentrating on practical changes such as wallpapers, ringtones and icon placements from an ergonomics aspect to increase usability and task efficiency. Their findings indicate that users prioritize practicality and routine-based adjustments, tweaking their phones to better fit their daily habits and reduce effort in frequent tasks. Marathe and Sundar (2011) employed experimental methods based on psychological and communication theory to learn why users choose to customize, specifically if customization is motivated by a desire for control or a desire to express personal identity. Their results show that while both control and identity are crucial, identity expression is a far more powerful motivator in personalization, particularly when users believe that the mobile phone system is flexible enough to allow meaningful modifications for self-representation and expression. Even with their different perspectives, both studies agree that customisation improves user satisfaction and increases the interaction between people and their gadgets.

In contrast to Chen and Chen’s 2016 journal article, the multidisciplinary approach by de Reuver, Nikou and Bouwman (2016) sheds light on the domestication process of smartphones and apps into daily life using a quantitative mixed-method approach combining log data and surveys. Whereas Chen and Chen (2016) focus on ergonomic design to enhance usability and task efficiency through practical personalization, de Reuver, Nikou and Bouwman (2016) examine how different app usage habits shape one’s daily activities, particularly social interactions. According to their findings, downloaded apps, especially social media and messaging apps, influence routines more than bundled software (ibid.). The study highlights that understanding domestication requires examining not just how often, but how long users interact with specific apps.

Lacohée, Wakeford and Pearson’s (2003) qualitative, sociological study takes a similar approach to Srivastava’s (2005) and Fortunati’s (2013) papers, albeit concentrating on different social aspects of everyday mobile telephony, such as how mobile phones evolved from exclusive commercial tools to personal, emotional and identity-driven devices that users can tailor to their needs. Lacohée, Wakeford and Pearson agree with Srivastava and Fortunati, arguing that mobile phones have become ubiquitous personal devices that meet emotional, social and utilitarian demands. According to Lacohée, Wakeford and Pearson (2003), mobile phones have transformed into more than just communication tools and serve as extensions of personal identities, enabling new kinds of presence, availability and social coordination. Their critique focuses on the so-called 24/7 culture, the need to be always connected, reachable and online, something they believe is an outcome of mobile connectivity (ibid.).

The Role of Trends and Fashion

Among the fierce competition of the blooming mobile phone market, Nokia paid serious attention to non-technical factors, such as distinctive design, usability and trends (e.g. Häikiö 2001, 81–2). Zhang and Juhlin’s (2016) research provides a hands-on look at the company’s design evolution from 1992 to 2013, focusing on the rise and fall of so-called fashion phones. According to them, one of Nokia’s success factors was the company’s fashion-oriented design paradigm, which became an integral part of their corporate identity.

Materials from the Nokia Design Archive reveal how the company gradually adopted the new design strategy. In an internal presentation, Nokia Mobile Phones Industrial Design and Styling Strategy (Nokia Corporation 1996), the role of fashion was recognized through styling, an ’art’ that could transform products from a functional tool to an ’object of desire’. To achieve the goal of fashionizing mobile phones, Nokia identified the diversity of user lifestyles and positioned personalization as one of the key design strategies for growth. The same presentation included a strategy roadmap that would achieve a modular product system and support substantial user customization by the beginning of the 2000s.

In Fashion – What Is It?, another internal presentation created around 2000, the importance of fashion for Nokia’s design strategy is even more evident. The company acknowledged fashion could be manifested not only in the designed object but also in its media imagery (Nokia Corporation n.d.a.). Design strategy presentations around the same period showcase the company’s efforts in crafting their public image through fashion magazines like BAZAAR and Vogue (Nokia Corporation 1996–1999). For Nokia (n.d.a), fashion was defined as ”a hybrid of commodity and fantasy,” where ’fantasy’ was the most value-adding element in sales. Other than the strategy presentations, numerous moodboards and user segmentation materials reflect the diversity of projected users as conceptualized by Nokia (see Figure 1).

Eventually, due to market changes, smartphone proliferation and consumer expectations, the design trend shifted back to standardization, with a demand for more minimalistic and touchscreen-centric designs that prioritized practicality and uniformity. These changes resulted in the gradual erosion of Nokia’s once-unique design identity. Zhang and Juhlin’s (2016) analysis demonstrates that the reduction in design-based personalization was not due to a lack of user interest, but rather industry-wide reforms that promoted standardization and global usability over personal expression.

Young people are particularly often drawn to styles and trends (Fortunati 2005; Oksman & Rautiainen 2003), which makes them more likely than older users to engage in mobile phone personalization. For a trend-conscious audience, aesthetics play a significant role, as noted by Fortunati (2005): “In order of relevance, style has already overtaken functionality and ’handiness’ as a criterion of purchase for the mobile phone.” The increasing marketing and portrayal of mobile phones in mass media contributed to normalizing their use even before it became widespread in practice. Two high-visibility examples from Hollywood blockbusters are the presence of Nokia’s 8110 ’banana phone’ in The Matrix (1999) and the 9210 Communicator in Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003), which lent some scifi cool to the Finnish brand.

An even clearer example of the rising pervasiveness of mobile phones is the coming-of-age teen movie Clueless (1995), where they are primarily portrayed as status symbols. The interaction of the main character, Cher Horowitz, with her mobile phone is casual and effortless, which aligns with her carefree and privileged lifestyle. Overall, in Clueless, the device is not just a tool for communication, but an integral part of the characters’ social identities. The frequency of mobile phone use in this movie surpassed the actual usage among young people at the time, with the device being an almost constant presence in the characters’ lives – the movie both predicted and satirized the obsession that would soon come to define contemporary culture.

Looking at Vogue and Vanity Fair magazines from the 1990s, mobile phones were described as small, sleek and personal, in line with the fact that they were becoming increasingly compact (Figure 2a). Noting the shift from the large, bulky models of the past and the lightweight new wave, Vogue 3/1996 stated that “ten years ago, you couldn’t flip open your cellular phone without dodging dirty looks,” whereas now you would want to show it off instead (see Figures 2b and 2c). Mobile phones were increasingly portrayed as a prominent part of the handbag, symbolizing both practicality and style. By this time, the diversity of projected users had already expanded far beyond businessmen and professionals.

Thus, media influence, people’s natural tendency to follow trends and the growing cultural significance of mobile phones all contributed to the rise of personalization. As Roland Barthes argues in The Fashion System (1990), fashion does not exist solely in the garment itself but is produced through a discourse, a structured system of meaning using language and image. Fashion photography and writing follow specific conventions distinct from ordinary communication. Similarly, the emerging discourse around mobile phones in the 1990s constructed them not only as communication tools but also as fashionable and personalized objects. The advertisements, magazines and promotional materials we examined, such as those found in Vogue, Vanity Fair, Iltalehti, as well as the design and marketing documents from the Nokia Design Archive, presented phones through stylized language and visual codes. In this sense, the discourse of mobile phone personalization mirrored the fashion system: it created a semiotic framework that encouraged users to see phones as extensions of identity, much like clothing.

Barthes (1990) identifies three structures through which fashion operates: the technological (the actual garment), the iconic (its photographic representation) and the verbal (its written description). A similar triadic system applies to mobile phones. The technological structure refers to the device’s physical form. The iconic structure appears in stylized advertisements. The verbal structure appears in promotional language and editorial content. The transitions between these structures do not happen effortlessly. Instead, they require what Barthes terms ’shifters’ to transition from one code to another. In our research, the advertisements, magazine features, and designers’ sketches and presentations function as such shifters, transforming the functional object into a desirable fashion accessory. Personalization, then, was not only a material practice but a discursive one, shaped by representations that encouraged users to see phones as wearable, symbolic and emotionally expressive.

Barthes (1990) draws a line between denotation, a pure, functional description and connotation, where language becomes rhetorical and expressive. In fashion writing, they observe how technical descriptions of garments are often poeticized, turning the material object into a site of meaning. Rather than simply informing the reader, the descriptive language used in fashion media often embellishes, stylizes or emotionally charges the garment, giving it a symbolic value. The interplay between matter and language gives rise to what they call ’poetics’ of description. Similarly, in mobile phone advertisements of the 1990s and early 2000s, product language frequently moved beyond technical specifications into the domain of connotation. Phrases like “let the colors speak” or “see red this Christmas” (IL Oct 2/1993; Dec 7/1998) did more than describe features: they projected moods and identities into devices.

Three Kinds of Personalization

Mobile phone personalization is a highly multidimensional subject that requires us to consider, for instance, different stakeholders, practices, trends, cost and technology. As an example of existing models, Comstock, Johansen and Winroth (2004) utilize Gilmore and Pine’s (1997) quadripartite model consisting of adaptive, cosmetic, transparent and collaborative customization when discussing the Swedish mobile industry. Blom and Monk’s (2003) model encompasses the reasons and effects of personalization from the user perspective instead. Using an established model could be beneficial, but when reflecting on the kinds of personalization that our initial charting turned up, a pragmatic typology emerged as a more viable alternative that serves the exact purpose of observing individual personalization features, their development and the stakeholders involved:

- External – physical personalization that does not require manufacturer support.

- Integrated – physical personalization where the default parts of the phone are modified on purpose.

- Digital – personalization that modifies the user interface.

Common examples of external personalization are phone cases and stickers. Neither of them requires support from the manufacturer side: any capable stakeholder can produce such products, which range from model-specific to generic. Even if manufacturer support was not necessary, they, too, produced and marketed such items, such as Nokia-branded belt cases. Already early on, such extras were often directly bundled with the phone itself. This category can also be considered to include diverse materials that were not even designed for mobile phones in the first place, but have been used for personalizing their look by resourceful users, as already seen in the earlier case of PHS phones (see Tajimax 2021).

The second category, integrated, refers to personalization that was consciously envisioned and facilitated by the manufacturer already at the design stage or, in other words, scripted into the device. As one example, offering a mobile phone in various colors was a first step that led to the next, replaceable case covers, which sparked a large third party aftermarket (see Section Integrated Personalization below for more). Some items that fall into this category could be labelled spare parts, as they also served that purpose. On the fence between external and integrated personalization sit, for instance, wrist straps and belt clips, which were mostly external in constitution, but typically required modest support from the manufacturer – at least a small attachment.

Digital personalization takes place in the electronic domain, which is why we have separated it from the two physical kinds. Unlike physical modifications, this kind of personalization is, conceptually thinking, just changing states of ones and zeroes in the device memory, even if they manifest themselves as visuals, sound and user interface changes. As above, the manufacturer has to offer support for this kind of personalization, which eventually grew from ready-made selectable options, such as ringtones, to the malleability of the smartphone.

External Personalization

Over time, the script of the mobile phone slowly began to expand from a communication device toward an accessory that could represent one’s identity and lifestyle. Fortunati’s (2013) analysis in Mobile Phones and Fashion in Post-modernity offers an interesting perspective on how mobile phones started carrying social and cultural significance beyond their functional purpose. They describe the mobile phone as a ’nomad’ on the body, moving from the pocket to the ear, crossing the body and its clothing. This dynamic movement challenges the static arrangement of objects on the body and disrupts the system of meanings in fashion (Fortunati 2005), making the device a fluid and ever-present object. With external accessories, such as lanyards, cases or belt clips, the phone can be carried around in different places, increasing its fluidity even further.

Oksman and Rautiainen (2003) cite Pasi Mäenpää, who suggests that the term kännykkä, the most common Finnish term for a mobile phone in its earlier days, implied that the phone was seen as an extension of the hand, the most important body part used for interaction with the environment. They also mention the gendered ways in which Finnish teenagers interacted with their mobile phones in the late 1990s. Mobile phones began proliferating among teenagers in 1997, when cheaper models and lower operator costs made them increasingly accessible. The attitude towards the device was at first cautious and respectful, recognizing it as a valued status symbol that in itself enhanced individuality. Gradually, teenagers began to see it as a consumer good. Boys often carried their phones attached to their waist with belt clips, ensuring it was visible to others. In contrast, girls typically kept their phones in their bags or pockets (ibid.). These tendencies, however, can vary greatly depending on the culture and context of each country.

External personalization, therefore, served both practical and expressive purposes. According to a 1996 archived snapshot of Nokia’s official website (”Nokia Accessories for Nokia 101”), the company already offered a wide collection of stylish carrying cases made of leather or fabric for the Nokia 101, with options to carry the phone with a wrist strap or belt clip. Among these was a green nylon carrying bag featuring an embroidered brand logo, as well as watertight pouches designed for splash protection. Otherwise, most of the early cases were simple-looking, black leather or fabric, often equipped with a belt clip or see-through front part. Belt clips were especially common and served not just as a convenience, but also as a way to keep the phone visible, clipped to trousers, bags or jackets. A marketing leaflet titled So Sophisticated, It’s Simple (Nokia Design Archive 1999) listed the belt clip under accessibility features, suggesting their importance in making the device easier to reach, both for general use and in special contexts, such as wheelchair mounting.

Although most of the cases listed on Nokia’s website in 1996 appeared minimalistic or utilitarian, a series of sketches titled Face the Fun, preserved in the Nokia Design Archive, reflects early exploration in expressive phone case styling (Figure 3). Annotated with the year range 1995–1997, Face the Fun includes a colored illustration presenting four case design concepts, black-and-white drawings of each concept and a clipping of marketing material featuring cases designed for the Nokia 8100 series.

In contrast to the minimal or ’businesslike’ aesthetics shown on the clipping, Face the Fun applied bold color combinations and free-form shapes to the four concepts: PRO-FILE, which showcases the phone through a cutout on the front; SMILE, which forms a smiley face with the curved edge of the pouch lid; WALT, which resembles the silhouette of Mickey Mouse; and MIRÓ, which draws inspiration from Spanish artist Joan Miró’s style for its playful fabric collage. These concepts demonstrated the possibility for conventionally professional-looking phones to become playful and expressive – the script of the device was evolving. Moreover, WALT and MIRÓ represented potential to collaborate with established brands and organizations in designing fashionable accessories.

Following the imaginative concepts of Face the Fun, stylish case designs and fashion house collaboration became a reality over the following years. Some examples from our material are third-party cases, described as ’new clothes’, such as luxurious mink fur cases and custom-designed ones, even a miniature bed for the mobile phone to rest in after a long day (Figure 4a). Some cases could be securely fastened to a belt, while luxurious leather bags featured extra details like a makeup mirror on the inside flap (IL Apr 18/1998). Another example of fashion-forward accessories was a Marimekko mobile phone case (IL Dec 5/1998). In collaboration with Nokia, Marimekko designed a genuine leather case for Nokia’s latest mobile phones. The advertisement highlights how the collaboration aimed to balance style and practicality, while also allowing Nokia to benefit from an established brand (see Figures 4b and 4c). The cases were sold both at Marimekko stores and Nokia retailers.

Along the lines of Face the Fun concepts, some unconventional options emerged in the market, such as the plushie mobile phone case (IL Dec 13/2000), which resembled a soft toy lizard and doubled as a glove, with the user’s fingers inside the lizard’s legs. While far from practical, it illustrated the playful and experimental direction accessories were taking in the yet unsettled market. These imaginative and sometimes unusually shaped phone cases seemed like a response to the diverse and continuously changing shapes of mobile phones during the late 1990s and early 2000s, reflecting an openness towards playful and outside the box ideas.

In addition to phone manufacturers and established fashion brands, several other vendors provided products and services for external personalization. Trends in Japan Summer 1999 (Nokia Corporation 1999), a trend forecasting presentation, reveals the company’s attention to the influence of street fashion and youth culture in personalizing consumer electronics (see Figure 5). The third page of the presentation summarizes ongoing trends of decorating mobile phones with stickers, paint, straps and different types of covers. The street vendor market in Japan not only sold materials for decoration, but also provided services, such as hand-painting phones according to customers’ designs. Likely because the hand-painting services resembled nail salons, the report also highlighted the newly emerged nail-painting ATMs in Japan and further speculated on the possibility of automated phone-painting machines.

In both this presentation and other photographs from the archive, Nokia’s design researchers observed and captured Japanese store displays with consumer electronics and accessories. Figure 6a is a snapshot from the Trends in Japan Summer 1999 presentation (Nokia Corporation 1999). The photo shows a store display of keychains that were designed to be stamps at the same time – these keychains could, naturally, be attached to mobile devices as well. According to the advertisement board above the display stand, these stamps could be used for name, telephone number and possibly other personal information. This act of attaching personal identification stationery to phones again serves as an example of the growing personal, emotional attachment between people and their phones.

Figure 6b is a photo taken by Nokia’s designer Anna Valtonen in the 1990s, possibly also for the study of Japanese mobile media culture. The image focuses on rows of colorful beaded trinkets hanging on display panels on a wall. Three mobile phones adorned with the trinkets are displayed at the sides of one panel, as examples advertising the accessories. In the background, the image shows a poster of snowboarding gear, a backpack with expressive patterns and a shelf of branded sneakers, hinting that the place might be a sportswear or street style retailer. Selling phone accessories in an apparel store reflects how the practices of personalizing mobile phones had already become part of fashion or lifestyle choices instead of solely about technical utility in the late 1990s of Japan. In addition, these market research materials from Nokia illustrate how designers studied the inscription of fashion in technological objects from different cultures.

Nokia’s interest in the Japanese market was certainly not arbitrary, as Japan had played a pioneering role in developing consumer electronics and telecommunication technology. In 1979, Japan’s state-owned monopoly Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) launched the world’s first cellular phone service (Okada 2006). In 1985, the government decided to reform the telecommunication sector by privatizing NTT and dividing it into multiple regional mobile companies. From 1988 to 1996, more than 20 new carriers entered the market. The policy thus generated relatively intense competition among the operators in contrast to other countries (Iimi 2005). In 1995, three operators started a phone service called the Personal Handyphone System (PHS) beside the already operating 2G cellular networks. Like common mobile phones, PHS handsets transmitted wireless signals through relay stations. However, the PHS utilized low level electromagnetic waves and required a less costly infrastructure (Ishii 1996). These characteristics of the network allowed the operators and retailers to lower the cost of the handsets and monthly subscription, expanding the consumer base (Okada 2006).

Young consumers’ DIY (do it yourself) culture of personalizing phone appearances exemplifies this accelerated popularization of mobile communications in Japan. In the blog Tajimaxの平成ガールズカルチャー論 [Tajimax’s Theory of Heisei Girls Culture], the blogger Tajimax included a page from the June 1997 issue of teenage magazine Popteen to exemplify the culture of デコ電 [deco-den, meaning ’decorated phones’] in the 1990s. Compared to the previously mentioned examples of Iltalehti and Vogue, Popteen adopted a more interactive approach to engage its audience. In the magazine image, the text indicates that the magazine was announcing the winners of its phone decoration contest named PHS OF THE YEAR. The open call was published in March 1996 and received as many as 3000 submissions.

After three months, the editors selected and published six winning designs. Three designs shown in the snapshots exhibit not only the winning readers’ personal interests, but also trending topics in the surrounding society: 赤道直下のジャマイカン [Jamaican on the Equator], ロコガールが持つアルバ [Rosa × alba held by loco girls] and ワイルドに驅け拔けるサバンナ [Running wild through the savanna]. The contest demonstrated the capability of consumers to accomplish elaborate designs fully by hand-painting techniques similar to nail art (Tajimax 2021). Furthermore, all of the winning readers appeared to be girls aged between 15 and 19, illustrating the shifting demographics of mobile users, as well as the new culture of adopting and personalizing mobile technology in the mid-1990s.

Our main research material did not reveal any comparable DIY case customization trend in Finland; as we discuss in the next section, case personalization itself was equally popular here, but it heavily relied on commercial offerings. As the examples above show, there was no monopoly on external personalization, as no single stakeholder could exert control over the ingenious and colorful ways phones were tweaked – when compared to the two other kinds, external personalization provided the most agency all the way down to the grassroots level.

Integrated Personalization

In 1992, Nokia introduced multiple color variants with their 101 model, allowing users to make their mobile phones reflect personal style. A Nokia 101 advertisement in Iltalehti (Oct 2/1993) showcased the device in six available colors, with a tagline “let the colors speak”. The text also mentions replaceable color covers, making it an early example of a manufacturer-scripted approach to individual expression through design. This shift toward personalization was already evident in earlier Nokia marketing materials from the Nokia Design Archive. The Nokia 101 was described not only based on its technical benefits – lightweight, compact, with large and soft keys – but also in aesthetic terms: “rest your eyes on the Nordic form, the clean lines,” emphasizing that aesthetics were integrated into usability, serving “all the needs of the user, including the aesthetic ones” (Nokia Corporation n.d.c.). Similarly, the Swatch fashion-centric TCE Series introduced in 1993 was available in four colors, with the TCE 121 even featuring a translucent variant with a see-through red front faceplate and blue back, which was quite unusual for that time (Mobile Phone Museum n.d.).

According to the Mobile Phone Museum (n.d.), Motorola started working with Swatch already in 1992, but the deal never came to conclusion due to the American company’s focus on business-centered design and corporate customers. However, the company decided to introduce customizable options later on, as the feature started becoming more commonplace in the market. Thus, the Motorola Flare was published in 1995. It was a base unit that could be modified with interchangeable front faces around the keypad. The Flare was designed to accommodate varying customer tastes and was offered in multiple color and design variants, including exclusive editions for specific retailers and operators.

In a Vanity Fair advertisement (3/1995), Motorola marketed a precursor to the Flare, mentioning the ’Motorola Flip cellular phone’, which may refer to a model of the MicroTAC series, stating that “A personal phone should keep things personal,” being “small, sleek and discreet”. This message positioned the phone as both functional and fashion-conscious, appealing to users who valued privacy alongside personal style. Similarly, in Vogue (8/1998), the Motorola StarTAC 3000 was marketed as a way to “get the look of the moment.” Following the trend of customization, Motorola continued to experiment with personalized designs after the Flare, notably with the StarTAC Rainbow, a colorful variant of the StarTAC 70 released in 1997. Inspired by the Volkswagen Polo Harlekin car, it reused surplus plastic from the Flare project. Although produced in limited quantities, it was well received in Southern Europe and considered a success by Motorola’s European team (Mobile Phone Museum n.d.).

In 1996, Ericsson announced the GA628 model, which included four interchangeable color panels for the keypad area, together with colored rings for the antenna. A thin sheet of plastic was a minimum effort solution to provide color personalization, but it does reveal how the Swedish company, too, tried to avoid falling behind in product development (Figure 8b). An Iltalehti advertisement (Sep 11/1996) mentions the Ericsson GF388, which stood out due to its replaceable keypad cover lid (see Figure 8a): as shown in the advertisement, the lid could be swapped out for several designs featuring artwork by prominent artists, such as Keith Haring, László Moholy-Nagy or Antoni Tàpies – in this case, the projected user was both trendy and cultured. The campaign took a playful tone, referring to the phone’s cover changeability with the phrase “Tomorrow you can have a new puppy. Or three. Or nine,” highlighting the flexible and imaginative nature of the feature.

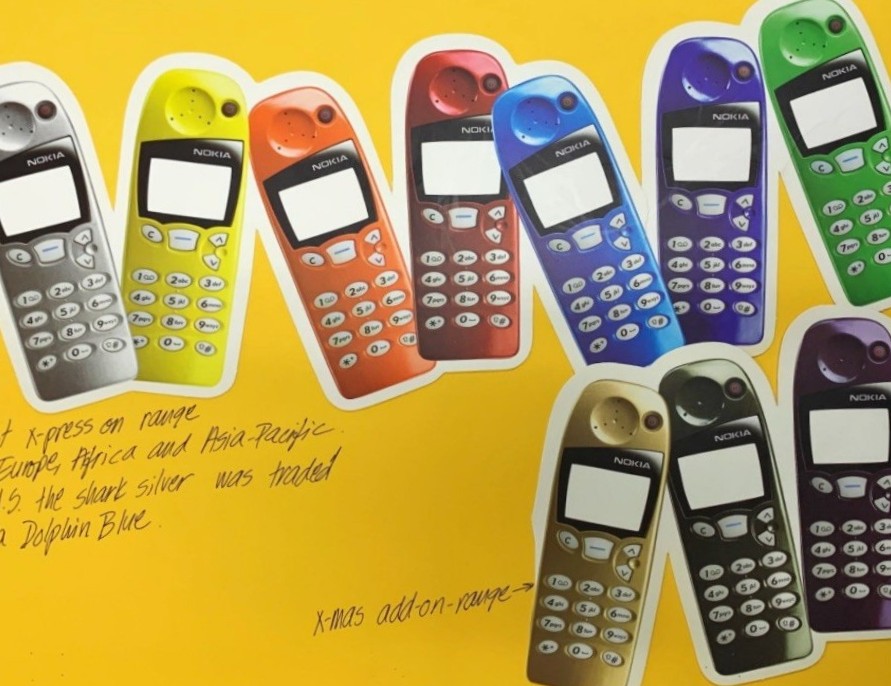

Together with its highly successful 5110 in 1998, Nokia announced the Xpress-on user interchangeable covers (Figure 9b), underlining how such personalization had already become an integral part of the script of the mobile phone. At the beginning, only a few covers were available, but soon the model became so popular that you could also purchase third-party covers, due to Nokia making the 3D design files open source (Mobile Phone Museum n.d.). This move made the options for customization almost endless and paved the way to a larger personalization boom a few years later. Nokia 5110 advertisements (IL Jul 1/1998; Vogue 4/1999) proudly demonstrated how easy it was to change the color of the phone by swapping out the Xpress-on covers, claiming that color could reflect one’s mood, outfit or occasion. Another advertisement (IL Dec 7/1998) also highlighted the Xpress-on covers with a tagline “See red this Christmas!” (see Figure 9a), inviting users to change the covers frequently to match different seasons and holidays.

In addition to covers, Nokia offered original changeable keypads, such as a black variant featured in accessory materials in the Nokia Design Archive (Figure 10b), allowing users to further personalize the feel and visual style of their devices. Nokia’s internal publication titled Effective Use of Colors, Materials and Finishes (2005) outlined how colors, textures and materials were used not only for visual appeal, but to elicit emotional responses and enhance perceived value. The document distinguishes between functional quality (measured through rigorous durability tests) and emotional quality, which was achieved through material combinations like chrome with plastic or glossy paint finishes. Designers were encouraged to provoke ’Wow!’ moments, immediate subconscious emotional reactions to color and form, through bold finishes, high-end details and even experimental surface treatments that responded to human interaction (see Figure 10a).

This focus on design as a means of emotional connection and identity expression became even more prominent in the marketing of the late 1990s models, such as the Nokia 8210 and 8810 (Nokia Corporation 1998–2000). The materials found in the archive emphasize not just usability, but emotional and stylistic appeal, speaking to ’trendsetters’ and reflecting a shift away from the “rational and traditional aspects toward a more lifestyle, fashion and fun oriented direction.” Colors available for the 8210, such as ’Red Pepper’, ’Lunar Yellow’ and ’Mocha Brown’ were tied to fashion trends, materials and sensory experiences, like the texture of velvet or the atmosphere of haute couture. This discourse framed phones as follows:

If you understand the difference between clothing and style, then you know the difference between a mobile phone and the Nokia 8210. You use a mobile phone to communicate with others, you own the Nokia 8210 to communicate something about yourself. (Nokia Corporation 1998–2000.)

The trend assumed a life of its own and extended beyond the original phone manufacturer, with third-party accessories becoming an integral part of personalization. Advertisements for the Nokia 3210 portrayed snap-on covers, as well as cross-platform accessories, such as a flashing antenna tip, which would light up when the phone rang (Figures 11a–b). Other advertisements (IL Apr 18/1998) for models, such as the Nokia 6110, explored the idea of mobile phone fashion and that mobile phones, much like humans, could be dressed in the latest trends, also showing the ability to have custom design covers made to order (Figure 11c). The introduction of colors, interchangeable covers and artistic designs opened the door for an expansive market facilitated by conscious design decisions and driven by consumer choice.

Digital Personalization

Mobile phone ringtones derived from the need to alert users to incoming calls, which passed down from electromechanical ringers on old landline telephones. As mobile phone technology advanced, manufacturers, such as Nokia, began including a wider range of tones, paving the way for customization and personalization. The transition from simple beeps to polyphonic melodies and later to true digital (MP3) ringtones enabled users to select tunes that represented their personal taste, allowing them to recognize callers without looking at their phones and to express themselves (Pfleging, Alt & Schmidt 2012). Nokia phones, such as the 2110 and Cityman 5000, had eight ringtones and vibrating batteries, while the Ericsson NH 238 had ’melodic’ ringtones with a vibrating battery. Devices also allowed users to designate different tones to various types of alerts and, thus, provided an early insight into the importance of sound and visual design for human identity (Licoppe 2010; 2011; Pfleging, Alt & Schmidt 2012).

As the mobile communication market grew, so did the demand for custom ringtones, alerts and notifications, once again highlighting the constantly changing script of the mobile phone. Especially with the emergence of feature phones in the early 2000s, customizable ringtones became increasingly popular and a lucrative product. By targeting both the general public and young people, operators and device manufacturers made a concerted effort to create an engaging user experience with this feature. Ringtones quickly turned into standalone products with licensed music clips and specially designed alert tones, opening up a new revenue stream and marketing channel for the mobile and music industries, resulting in billions of dollars in global revenue (e.g. Gopinath 2013).

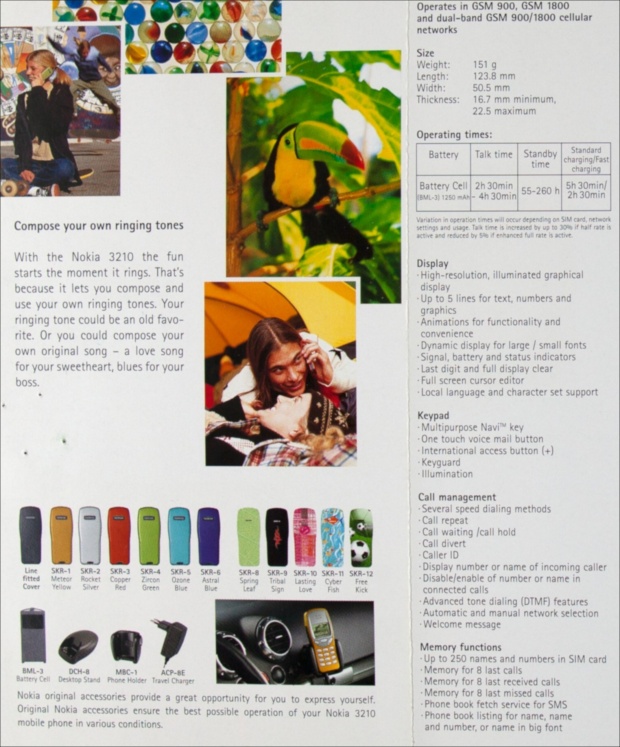

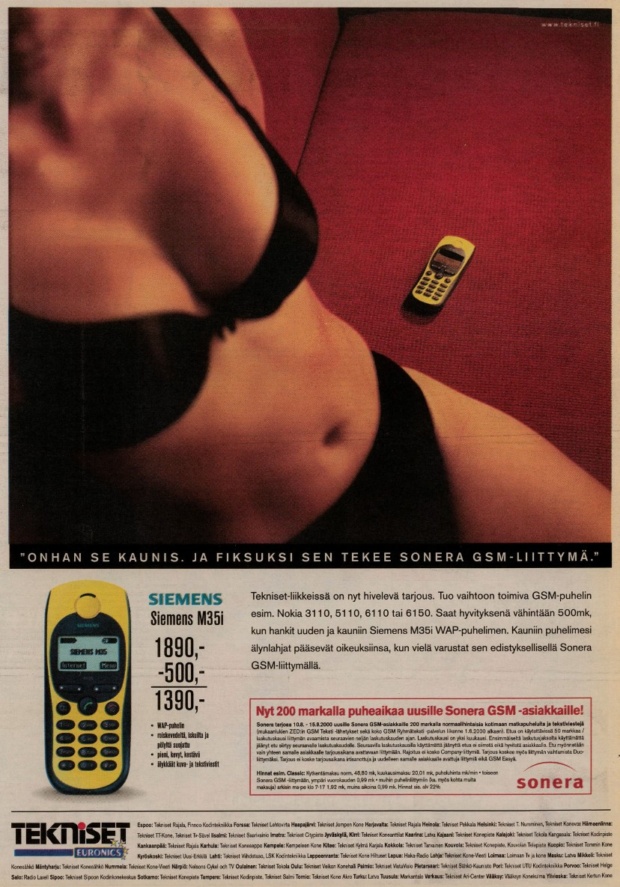

Plenty of mobile phone advertisements promoted phones’ most recent technical features, such as eight megabytes of memory, a long battery life, and even fax and email capabilities built into the handset, as something that must be obtained to remain current or popular. Ringtones were mentioned on a few occasions: for example, the Sonera advertisement of the time (now Telia) marketed the Siemens C25 model (Figure 12a) with composable ringtones, as well as the device’s portability and compact size. The Pioneer PCC-D500 model (Figure 12b) was also marketed as having ’musical’ ringtone capabilities. For the Nokia 3210, released in 1999, the marketing material highlighted its built-in composer feature (Figure 13) that users could utilize to create their own original ringtones and assign them to each contact according to different life scenarios: ”[…] a love song for your sweetheart, blues for your boss” (Nokia Corporation 1998–1999).

Commercials for purchasing ringtones from various vendors were diverse and often highly detailed, as can be seen in advertisements selling the most popular hit songs of the time or nostalgic tunes from the past. For instance, Figure 14a contains categorized ringtones ranging from classical Sibelius to the theme from Mission: Impossible 2 (2000) and the 1970s’ rock anthem Sweet Home Alabama (1974) by Lynyrd Skynyrd. Ringtones could also be purchased as gifts for friends or even as Christmas greetings, as illustrated by the early 2000s’ and late 1990s’ advertisement (Figures 14a and 14b).

Another customizable feature of early mobile phones was the basic management of contacts, which allowed users to save frequently used numbers and assign them to fast dial slots. When the calendar capability was introduced circa 1994, the applications quickly enabled users to enter, store and manage personal information, transforming each phone into a personalized organizer. These additions demonstrate how the designers tried to anticipate the needs of the ever-changing projected user. Manufacturers began to integrate customization features, such as digital address books and calendars, to accommodate the growing need for on-the-go personal management. For example, the IBM Simon Personal Communicator, released in 1994, included a digital contact book and calendar that helped professionals plan their schedules by tracking important dates and appointments.

Users were allowed to modify the look and feel of their user interfaces to some extent by changing the fonts, colors, logos and wallpapers. They could also customize their menu hierarchy and select the features they deemed most important for quick access. Battery settings were, likewise, customizable already in the very early mobile phones, due to the practical benefits of obtaining a longer battery life (Choe, Liao & Sun 2012). The Nokia 2110 was one of the first models to include rudimentary profiles, predefined configurations that automatically altered the volume, vibration and ringtone settings, ranging from ’Silent’ to ’Outdoor’. Many of the initial personalization options were predefined by the manufacturers and allowed users to modify their devices only to a limited extent – these restrictions remain somewhat current even today, in terms of how users may operate and tweak their devices.

Initially, mobile phone logos and wallpapers were restricted to simple operator text logos, which displayed the network carrier’s name on the home screen. As phone displays transformed from monochrome text to low-resolution graphic LCDs in the late 1990s and early 2000s, customers were able to replace static operator text logos with pixel-based graphics. These simple monochrome bitmap images facilitated expression and branding beyond plain words. The Nokia 6110 (1997) and Siemens S35 (1999) were among the first to support the feature. Simultaneously, as display technology advanced, screensavers and wallpapers grew more configurable, allowing users to upload or download basic graphics to personalize the idle screen or background. The transition from text to pixel logos signaled the beginning of a trend for visual customization on mobile devices, which later resulted in full-color wallpapers, animated screensavers and dynamic themes in smartphones.

Early mobile phone advertising styles were largely uniform and comparable, with an emphasis on the most recent technological breakthroughs, which is well in line with their initial audience. Rather surprisingly, only a few of the advertisements studied for this article mentioned or focused on mobile phones’ visual personalization capabilities, even when the devices had already proliferated in the market. The 1999 Siemens S25 (Figure 12) Sonera advertisement cited the device’s six-row color screen and the Siemens M35i (Figure 15) was marketed as offering even MMS (Multimedia Messaging Service) capabilities, ‘intelligently’, of course. Otherwise, the marketers largely employed identical vocabulary from advertisement to another, with each unique technical detail being intelligent, smart, convenient and straightforward to use.

As in the case of ringtones, the advertisements for operator logos and wallpapers were diverse, detailed and varied in shape, size and vocabulary. It was also highly common to sell all three next to each other. The monotone-colored spring commercial (Figure 16a) from the early 2000s featured 20 logos ranging from Pac-Man to The Communist Manifesto, as well as 14 screensavers ranging from censored R-rated versions inappropriate for children to a Mona Lisa screensaver. Cramming the advertisements full of merchandise appears detrimental to readability, but from the vendor perspective it made perfect sense to try to cater to all prospective clients and use the paid space effectively. At this point, digital personalization was far from universal, as the ads’ phone lists reveal: most of the time Nokia was the only supported brand and even then, a too old model would not suffice.

Another advertisement in color (Figure 14a) marketed logos ranging from animals to band themes and bumpkin humor slogans. On a general level, many of the advertisements appear to be erratic, as the formats, colors, fonts, and layouts differ from one another. However, some of the advertised logo, wallpaper and screensaver topics are similar, with the same band logos, censored R-rated content or slogans. One advertisement (Figure 16b) complimentarily stands out from the others as it promotes purchasing a high school graduation greeting logo for the recent graduate. According to a price comparison published in Iltalehti (Mar 3/2000), logos cost about 3–5 marks, roughly a euro in today’s money – not a small sum, but apparently acceptable to the audience.

To summarize, digital personalization was very limited in the early days of mobile phones, but nevertheless had a notable impact on shaping user identity and ownership. As displays evolved from monochrome text to basic pixel-based graphic LCDs in the late 1990s and early 2000s, users could replace static operator text by a customized logo and download basic bitmap images, paving the way for increased visual personalization. Basic features, such as custom ringtones, operator logos and, subsequently, screensavers and wallpapers allowed customers to personalize devices that were, initially, largely homogeneous. Although early digital personalization concentrated on rather minor cosmetic features, it was a significant step toward making phones reflect personal style and social identity, foreshadowing the far more comprehensive customization capabilities of modern smartphones.

Conclusion

Over the approximately ten years covered by our study, the mobile phone underwent great technical, commercial and cultural changes. Personalization touches upon all of them, as it heavily depended on technical facilitation, was quickly commercialized, and both reflected and shaped contemporary mobile phone culture. One of our clearest observations is the progressive nature of personalization: black covers turned into a selection of colors and then snap-on covers, fixed ringtones evolved into predefined sets and finally something you could buy from a service, and so on. The steps between these stages were typically small, at times relying on creative repurposing of features initially intended for other uses. In addition to being the market leader, Nokia can also be labelled the personalization leader, as many of the examples above illustrate – they either originated from the company or, in some cases, were exclusive to its models.

When applying Akrich’s (1992) concepts of script and projected user, it is easy to observe that they both underwent significant changes over the 1990s and early 2000s. The initial projected user was the professional, the businessman, but new groups were quickly added to the roster when Nokia and its competitors started targeting the mass market. It is an oversimplification to claim that young and trendy audiences were the only customers interested in personalization, but their presence is definitely prominent in most kinds we have described here. The script of the device, likewise, shifted from a utility toward something else: personal, flexible, fashionable and fun (cf. Barthes 1990).

Our study highlights how personalization was carried out by a complex network of stakeholders – or actors to be in line with Akrich’s (1992) actor-network theory based terminology – ranging from enterprises to small businesses and, at the other end of the scale, individual users. The simplified view of companies providing products in interaction with its customers is clearly inadequate here. Operators, resellers, publishers, fashion houses and the colorful cottage industry that provided ringtones and operator logos were other players involved with early mobile phone personalization. The borders between the actors were not necessarily well-defined, as it was common for the same company to have multiple simultaneous roles: for instance, operators sold ringtones and phone companies designed accessories. Furthermore, users cannot be considered as a mere target audience, as they, too, actively shaped the mobile culture of the time, redefining what the mobile phone was in the first place.

When trying to assess the validity of our findings, some possible blind spots come to mind. Firstly, given the variety of personalization, it is probable that our sample of magazine advertisements and articles missed some individual features, even though the most common ones were found. Secondly, given the nature of the research material and the volatility of external personalization, the discoveries mostly represent commercially available or publicly discussed features. For instance, someone slapping a sticker of their favorite band on the phone would not turn up here, but would require a completely different study altogether. Our tripartite typology served the purposes of this paper and could be expanded into a complete model if necessary, but applying it as is to even today’s smartphones would be problematic, as their personalization is already so different to the early models we have discussed.

Two themes manifest themselves in several ways in all three of our categories: control and facilitation. In the case of external personalization, the manufacturer had least control over what happened after the phone became someone’s property, whereas integrated personalization was much more planned and controlled (cf. Choe, Liao & Sun 2012). Digital personalization was initially non-existent and companies could precisely decide what could be done or not. As in the case of integrated personalization, some of this control had to be given away to facilitate third parties’ and users’ endeavors, at times leading to unexpected results and diverging from the original script embedded in the device. Another commonly needed facilitator for software-based personalization was the operator, who would relay content through their mobile networks.

When the mobile phone turned into a commodity and reached new audiences, it quickly sparked a personalization boom and gave birth to a complete industry revolving around it. The phone manufacturers of the time could hardly have anticipated the level of interest, but they were certainly quick to capitalize on it. On the one hand, users wanted and could express their individuality by personalizing their phones – yet, on the other hand, integrated and digital options were initially so limited that, in reality, there was almost nothing unique about them. Quickly moving and unsettled practices lead to several colorful dead ends and overkills that have since disappeared. While today the software side has exploded far beyond the capabilities of early devices, the phones themselves have converged into physically uniform slates with little left of the diversity that was experienced at the turn of the millennium.

Acknowledgements

We thank Petri Saarikoski and the Nokia Design Archive, university archivist Riina Ojanen in particular, for their help. This research was supported by the Academy of Finland funded Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies (CoE-GameCult, decision number 353268).

References

All links verified October 29, 2025.

Magazines and Newspapers

Iltalehti (IL) Jan 11/1991, Oct 2/1993, Apr 21/1994, Oct 8/1994, Nov 25/1994, Mar 31/1995, June 30/1995, Apr 11/1996, Sep 11/1996, Oct 30/1996, Feb 25/1997, Mar 19/1997, Nov 28/1997, Apr 18/1998, May 20/1998, Jul 1/1998, Sep 5/1998, Sep 11/1998, Nov 6/1998, Dec 5/1998, Dec 7/1998, Feb 6/1999, Jun 30/1999, Aug 30/1999, Sep 18/1999, Sep 20/1999, Dec 10/1999, Dec 23/1999, Feb 24/2000, Mar 22/2000, Jun 6/2000, Sep 11/2000, Dec 13/2000, Mar 7/2001, June 2/2001, June 20/2001, Apr 3/2002, Nov 24/2006, Jan 24/2007

Vanity Fair 3/1995, 6/1998, 6/1999, 12/1999

Vogue (US Edition) 3/1995, 5/1995, 9/1995, 10/1995, 3/1996, 2/1997, 10/1997, 11/1997, 8/1998, 11/1998, 4/1999, 5/1999, 11/1999, 12/1999

Nokia Design Archive

Becerra, Liliana, Janina Hihnala, Tasha Kim, Gregor Magnusson & Todd Wood. 2005. Effective Use of Colors, Materials and Finishes. Nokia Design Calabasas, Description: julkaisu, värien ja materiaalien merkitysten pohdintaa, ohjeistuksia, tuotevertailua, inspiraatiomateriaalia, muotoiluratkaisujen kuvailua. Mukana saatekirje. [Publication, Reflections on the Meanings of Colors and Materials, Instructions, Product comparisons, Inspirational material, Descriptions of Design Solutions. Includes a Cover Letter]. Box 5, Julkaisut [Publications].

Kranck, Zina. 1995–1997. Face The Fun: Luonnoksia, asusteet ja kantolaukut [Sketches, Accessories and Carrier Bags). Donated by Zina Kranck. Folder 2, Isokokoiset [Large Size Files].

Kranck, Zina. 1998–1999. Seriously Fun 5110, 3210: Luonnoksia, markkinointimateriaalia, vaihdettavat kuoret, asusteet [Sketches, Marketing Material, Interchangeable Covers and Accessories]. Donated by Zina Kranck. Folder 2, Isokokoiset [Large Size Files].

Nokia Corporation. 1996. Nokia Mobile Phones Industrial Design and Styling Strategy, Presentation. Description: Presentation, description of design work, inspirational material. https://repo.aalto.fi/uncategorized/IO_f7154ed7-2ac7-4575-a9a6-51e4c25b8be3/.

Nokia Corporation. 1996–1999. What is Nokia design, presentation. Description: Untitled presentation explaining Nokia design strategy and the importance of design. https://repo.aalto.fi/uncategorized/IO_2b758154-e374-4aa3-aa18-fe446cc89001/

Nokia Coorporation. 1998–1999. Seriously Fun 5110, 3210: Luonnoksia, markkinointimateriaalia, vaihdettavat kuoret, asusteet [Sketches, Marketing Material, Interchangeable Covers and Accessories]. Donated by Zina Kranck. Folder 2, Isokokoiset [Large Size Files].

Nokia Corporation. 1998–2000. 8210, 8810, 8850, 8890. Description: Markkinointimateriaalia, lehtileikkeitä [Marketing Material, News Clippings]. Donated by Zina Kranck. Folder 2, Isokokoiset [Large Size Files].

Nokia Corporation. 1999. So Sophisticated, It’s Simple. Folder 1, Markkinointimateriaali [Marketing Material].

Nokia Corporation. 1999. Trends in Japan Summer 1999. Description: Reporting trends in fashion, pop culture, games, design and technology in Japan. https://repo.aalto.fi/uncategorized/IO_ba94702c-c74a-4f6d-9ad5-d1bf2745c9ec/.

Nokia Corporation. n.d.a. Fashion – What Is It?, presentation. Description: Presenting the relationship between fashion and mobile phones. https://repo.aalto.fi/uncategorized/IO_72d7a725-c1e2-428c-beda-0ffaf1f8b857/.

Nokia Corporation. n.d.b. Moodboard and user segmentation, presentation. Description: Moodboard and user segmentation. https://repo.aalto.fi/uncategorized/IO_5899a2d7-fcf7-4cd8-8031-503b86ed1539/

Nokia Corporation. n.d.c. Nokia 101. Folder 1, Markkinointimateriaali [Marketing Material].

Valtonen, Anna.1990–1999. Japanese store display 2. Description: Image of Trinkets in a Japanese Store. Photographer Anna Valtonen. https://repo.aalto.fi/uncategorized/IO_d3136333-0978-45cf-8b54-b02a00ab66b4/.

Websites

”Mobile Phone Museum.” n.d. https://www.mobilephonemuseum.com/.

”Nokia Accessories for Nokia 101.” 1996. Accessed via Internet Archive. https://web.archive.org/web/19961220014926/http://www.nokia.com/products/phones/accessories/acc_101.html.

”Nokia Design Archive.” 2025. https://nokiadesignarchive.aalto.fi/.

Tajimax. “00sガールズアイテムプレイバック #1 デコ電 [00s Girls’ Item Playback #1 Decorated Phones].” Last modified June 28, 2021. https://note.com/tajimax/n/nabf1eba7d762.

Literature

Akrich, Madeleine. 1992. ”The De-scription of Technical Objects.” In Shaping Technology/Building Society, edited by Wiebe E. Bijker & John Law, 205–24. MIT Press.

Bar, François, Matthew S. Weber & Francis Pisani. 2016. ”Mobile Technology Appropriation in a Distant Mirror: Baroquization, Creolization, and Cannibalism.” New Media & Society 18 (4): 617–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816629474.

Barthes, Roland. 1990. The Fashion System. University of California Press.

Blom, Jan O. & Andrew F. Monk. 2003. ”Theory of Personalization of Appearance: Why Users Personalize Their PCs and Mobile Phones.” Human–Computer Interaction 18 (3): 193–228. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327051HCI1803_1.

Brummett, Barry. 2009. Techniques of Close Reading. Sage.

Chen, Wei-Jen & Li-Chieh Chen. 2016. ”A Study of How Users Customize Their Mobile Phones.” In Advances in Cognitive Ergonomics, edited by Gavriel Salvendy & Waldemar Karwowski, 1st ed., 212–219. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/EBK1439834916-22.

Choe, Pilsung, Chen Liao & Wei Sun. 2012. ”Providing Customisation Guidelines of Mobile Phones for Manufacturers.” Behaviour & Information Technology 31 (10): 983–994. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2011.644581.

Comstock, Mica, Kerstin Johansen & Mats Winroth. 2004. ”From Mass Production to Mass Customization: Enabling Perspectives From the Swedish Mobile Telephone Industry.” Production Planning & Control 15 (4): 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/0953728042000238836.

de Reuver, Mark, Shahrokh Nikou & Harry Bouwman. 2016. ”Domestication of Smartphones and Mobile Applications: A Quantitative Mixed-Method Study.” Mobile Media & Communication 4 (3): 347–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157916649989.

Fortunati, Leopoldina. 2005. ”Mobile Phones and Fashion in Post-Modernity.” Telektronikk 101 (3–4): 35–47.

Fortunati, Leopoldina. 2013. ”The Mobile Phone between Fashion and Design.” Mobile Media & Communication 1 (1): 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157912459497.

Gilmore, James H. & B. Joseph Pine II. 1997. ”The Four Faces of Mass Customization.” Harvard Business Review 75 (1): 91–101. https://hbr.org/1997/01/the-four-faces-of-mass-customization.

Gopinath, Sumanth. 2013. ”This Business of Ringtones: The Unstable Value Chain and Accumulation of Capital by Rent in the Global Ringtone Industry.” In The Ringtone Dialectic: Economy and Cultural Form, 1st ed., 28–81. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Haddon, Leslie, ed. 1997. Communications on the Move: The Experience of Mobile Telephony in the 1990s. COST 248 Mobile Workgroup.

Häikiö, Martti. 2001. Nokia oyj:n historia 3: Globalisaatio. Telekommunikaation maailmanvalloitus 1992–2000. Edita.

Häkkilä, Jonna & Craig Chatfield. 2006. ”Personal Customisation of Mobile Phones: A Case Study.” In Proceedings of the 4th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Changing Roles (NordiCHI ’06), 409–412. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1182475.1182524.

Iimi, Atsushi. 2005. ”Estimating demand for cellular phone services in Japan.” Telecommunications Policy 29 (1): 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2004.11.001.

Ishii, Kenichi. 1996. ”PHS: revolutionizing personal communication in Japan.” Telecommunications Policy 20 (7): 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-5961(96)00032-8.

Jaakkola, Hannu, Moncef Gabbouj & Yrjö Neuvo. 1998. ”Fundamentals of Technology Diffusion and Mobile Phone Case Study.” Circuits, Systems and Signal Processing 17 (3): 421–448.

Koskinen, Ilpo & Esko Kurvinen. 2005. ”Mobile Multimedia and Users: On the Domestication of Mobile Multimedia.” Telektronikk 3–4/2005: 60–68.

Lacohee, Hazel V., Nina Wakeford & Ian Pearson. 2003. ”A Social History of the Mobile Telephone with a View of Its Future.” BT Technology Journal 21 (3): 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025187821567.

Lehtonen, Turo-Kimmo. 2003. ”The Domestication of New Technologies as a Set of Trials.” Journal of Consumer Culture 3 (3): 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/14695405030033014.

Leung, Lois & Ran Wei. 1999. ”Who are the Mobile Phone Have-Nots? Influences and Consequences.” New Media & Society 1 (2): 209–226.

Licoppe, Christian. 2010. ”The ‘Crisis of the Summons’: A Transformation in the Pragmatics of ‘Notifications,’ from Phone Rings to Instant Messaging.” The Information Society 26 (4): 288–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2010.489859.

Licoppe, Christian. 2011. ”What Does Answering the Phone Mean? A Sociology of the Phone Ring and Musical Ringtones.” Cultural Sociology 5 (3): 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975510378193.

Marathe, Sampada & S. Shyam Sundar. 2011. ”What Drives Customization? Control or Identity?” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’11), 781–790. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979056.

Okada, Tomoyuki. 2006. ”Youth Culture and the Shaping of Japanese Mobile Media: Personalization and the Keitai Internet as Multimedia.” In Personal, Portable, Pedestrian: Mobile Phones in Japanese Life, edited by Mizuko Ito, Misa Matsuda & Daisuke Okabe, 41–60. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5309.003.0005.

Oksman, Virpi & Pirjo Rautiainen. 2003. ”Perhaps It Is a Body Part: How the Mobile Phone Became an Organic Part of the Everyday Lives of Finnish Children and Teenagers.” In Machines That Become Us: The Social Context of Personal Communication Technology, edited by James Everett Katz, 293–308. Transaction Publishers.

Pantzar, Mika. 2000. Tulevaisuuden koti: Arjen tarpeita keksimässä. Otava.

Pfleging, Bastian, Florian Alt & Albrecht Schmidt. 2012. “Meaningful Melodies: Personal Sonification of Text Messages for Mobile Devices.” In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction With Mobile Devices and Services Companion (MobileHCI ’12),189–192. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2371664.2371706.

Rogers, Everett M. 1962. Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press of Glencoe.

Silverstone, Roger. 2006. ”Domesticating Domestication. Reflections on the Life of a Concept.” In Domestication of Media and Technology, edited by Thomas Berker, Maren Hartmann, Yves Punie & Katie Ward, 229–248. Open University Press.

Silverstone, Roger, Eric Hirsch & David Morley. 1992. ”Information and Communication Technologies and the Moral Economy of the Household.” In Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Spaces, edited by Roger Silverstone & Eric Hirsch, 15–31. Routledge.

Srivastava, Lara. 2005. “Mobile Phones and the Evolution of Social Behavior.” Behaviour & Information Technology 24 (2): 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290512331321910.

Zhang, Yanqing & Oskar Juhlin. 2016. “The ‘Life and Death’ of Great Finnish Fashion Phones: A Periodization of Changing Styles in Nokia Phone Design between 1992 and 2013.” Mobile Media & Communication 4 (3): 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157916654510.