program listings, computer magazines, game history

Jaakko Suominen

jaasuo [a] utu.fi

Ph.D., Professor of Digital Culture

University of Turku

Tero Pasanen

Ph.D.

Digital Culture

University of Turku

Tero Pasanen (1978–2022) in memoriam

How to cite: Suominen, Jaakko & Tero Pasanen. 2025. ”Digital Versions, Clones and Original Ideas: Game Code Listings in Finnish Computer Magazines, 1978–1990”. WiderScreen Ajankohtaista. https://widerscreen.fi/numerot/ajankohtaista/digital-versions-clones-and-original-ideas-game-code-listings-in-finnish-computer-magazines-19781990/

An earlier in Finnish-language version was published in Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja (Yearbook of Game Studies) 2020. Republished with a permission.

The article provides a broad overview of game code listings that have been published in Finnish computer magazines. The time frame encompasses the emergence as well the eventual end of their publication. The article maps how extensive of the publication of the code listings was, the variations between the publications and reporting who authored the listings. In addition, the article answers the question regarding why the program listings were created and published. The research material consists of about 1300 program listings, over 450 of them games, from 11 Finnish computer magazines. From a theoretical perspective, the article associates itself with previous studies on game history, home computing history as well as cultural software studies.

Introduction

In January 2016, Finnish president Sauli Niinistö, visited a children’s coding school at the Helsinki Library 10. Niinistö sat down at a computer and learned how to move a turtle on the screen via coding. According to Iltalehti (Pudas 2016), ‘Niinistö said after the coding session that the most important thing in coding is placing the space in the right place’. Niinistö’s visit to the coding school was part of the programming and coding boom of the 2010s, during which coding skills were viewed as a general civic skill as well as a form of IT competence. These skills were seen as important not only from the perspective of working life but also for the use, modification and understanding of IT services. The widespread development of coding skills could be seen as a national and international political goal. The ability has been considered both as a user’s capacity to program applications for digital devices and, in a broader context, as a skill to consider diverse things as processes that can be broken down and controlled (Tuomi et al. 2018).

Recent discussions about coding are not unique. Several decades earlier, coding (or computer programming) had already been envisioned as a future civic skill (see, e.g., Saarikoski 2006). The earlier history—and the central role of game programming therein—is easily forgotten in current discussions. The goal of this article is to examine the earlier history of programming more closely, focusing on game programming as a hobby and associated publishing activities surrounding the topic.

The first wave of information about broader hobbyist-led programming came about nearly forty years ago. The use of microcomputers became more common in the early 1980s in Finland and many other countries, while the average age of users dropped. Computers for personal use, which were pre-assembled and cheaper than ever before, had been entering the market since the late 1970s. However, it was the release of new devices, such as the Commodore VIC-20, Commodore 64 (C64), Sinclair ZX-81 and Sinclair Spectrum, which served to expand the home computer user base in the early 1980s. In addition to these devices, many other machines appeared on the market, most of which were incompatible with each another. At that stage, even though computer sales numbers were still only in the thousands or tens of thousands, the new information technology that spread to homes, schools and workplaces reached far more people than before. The increasing prevalence of computers and software was linked to discussions about the information society and the skills it required from its citizens (see, e.g., Saarikoski 2004).

As the use of computers became more widespread, so too did the need for knowledge about them. Computer clubs served as places for exchanging information and software, but they didn’t reach or interest all enthusiasts. Consequently, various printed publications began to target the growing user base and information about computers and coding spread through guidebooks and magazines. These magazines were published by device importers, user clubs and associations, as well as commercial publishers, whose publications ultimately reached the most readers.

The computers needed programs to function, and a significant part of the appeal of home computers was that users could program them themselves. Magazines began to publish program listings, as they were inexpensive and met the needs of readers by developing their programming skills and expanding the range of programs available to them (see also Haddon 1988; Saarikoski 2004). As the program listings were often submitted by the readers themselves, their publication formed an interactive relationship between the magazine’s editorial team and its readers.

Program listings were written in the BASIC language[1] or another programming language, such as assembler, and printed on the pages of magazines or books. With the listing, users could copy the program character by character and line by line onto their own computer. Afterward, the program could be saved to contemporary storage media such as floppy disks or cassette tapes. Manual copying was slow and prone to errors. These listings included games and various entertainment programs, utilities related to game development and other programming, extensions for the built-in BASIC interpreters of the machines, tools for handling storage media, graphic and music editors as well as and utilities suitable for tasks such as filing, statistical computation and word processing.

The publication of listings in Finland was based on international models such as the CLOAD and Computer & Video Games (CVG) magazines, though there were differences therein. In Finland, magazines did not often publish ready-made cassette or disk supplements but focused on printed programme listings. This decision was driven by cost factors. Due to the small size of the Finnish market, magazines did not focus on a single machine but instead sought to serve users of various brands and models.[2] Most often, the program listings came from the readers of the magazines, and the editorial team tested the programs for functionality, selected the best ones for publication, prepared the necessary accompanying texts and, in many cases, paid a small fee to the authors of the published programs.[3]

Alongside the program listings, magazines usually published a brief introduction explaining the content and purpose of any mentioned program. In some cases, magazines also provided a more detailed explanation that went through the program code in more depth, the purpose of which was to make it easier for users to modify the code for their own needs (see also Haddon 1988, 223). The authors of the program listings were not usually discussed in detail, with only their names being mentioned. As the programs became more complex, new machines entered the market and as commercial offerings increased, the need for entire program listings decreased. By the late 1980s, such listings were rarely published, as magazines began to deliver programs to readers in electronic form. Programs spread through diskettes, CD-ROMs, electronic services and later, the internet.

In this article, we examine program listings published in Finnish magazines, focusing particularly on game listings and other entertainment programs[4] such as utilities related to betting. We have searched for listings in all Finnish general interest, club and computer magazines available to us through university legal deposit libraries or as digitised versions. The material includes 1,290 program listings published in 11 computer magazines between 1978 and 1990. Of these, 454 are games or game-like entertainment programs. Additionally, there are listings that directly support game development, such as for implementing graphics, movable game characters and sound effects.

Our research questions are as follows:

- What factors influenced the publication of program listings, the beginning of the publishing activity and its eventual cessation?

- What were the focuses and characteristics of these publications?

- Who were the creators of the listings and what united or distinguished them?

After the introduction, the article is divided into sections where we first present previous research, especially in the areas of cultural software studies and the history of computer hobbies. We then offer a review of our material and research methods, introducing the magazines and their differences. Next, we examine game listings and divide the studied period into three different phases based on the publishing channels and the popularity of game listings. Before our conclusion, we also analyse the creators of game programs and categorise them into groups.

Previous Research

In the 21st century, there has been an increase in humanities and social sciences research related to computer programs. Within the so-called field of software studies, various interactional relationships between software and their users have been identified (see e.g., Fuller 2008; Manovich 2013). Similarly, for example, in the history of information technology, more attention has been paid to questions related to software in addition to hardware. This research has covered topics such as the software industry, the development of individual programs and user cultures (see e.g., Campbell-Kelly 2004; 2007). The demoscene[5] and other coding-related subcultures have also been studied (see especially Reunanen 2017). Game studies in a sense, form their own field within broader software studies, despite game studies not typically being contextualised as part of software studies.

In her dissertation in media studies, Minna Saariketo (2020) describes the landscape of code. Using this term, Saariketo refers to how programmed environments are present in people’s everyday lives in various ways. These landscapes of code both limit and guide people’s conditions for action, but users can also actively influence the landscapes around them. Pekka Mertala and his colleagues (2020) have discussed code as a form of socio-material text. According to them, coding should be examined broadly within a societal context, with a willingness to address the ideological and economic ties that sometimes underpin coding presented in a neutral manner. Although researchers have identified landscapes of code and coding cultures as 21st century phenomena, the terminology of contemporary cultural research can partially be applied to earlier periods.

There is also previous research on program listings themselves. For example, in his dissertation Koneen lumo, Petri Saarikoski referred to program listings as part of the development of Finnish computer hobbyism, highlighting the role of listings, especially in the early stages of computer hobbyism in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Saarikoski 2004, e.g., 67). Likewise, several international studies have also highlighted the cultural significance of program listings—or, more broadly, programs written by hobbyists—especially in the early 1980s (Haddon 1988; Swalwell 2008; Kirkpatrick 2017; Halvorson 2020). Internationally, entire works have been devoted to short individual programs (Montfort et al. 2013). Research on individual program listings has also begun in Finland in recent years. This research has involved analysing the program code itself, contextualising the listings in relation to the computing practices of their time and examining individual programs as part of the cultural heritage of computer hobbyism (Saarikoski et al. 2017; 2019).

Jaroslav Švelch (2018), in his work on early home computer and gaming hobbyism in Czechoslovakia, has written about listings and other programs published or distributed as coding acts.[6] By the term coding act, Švelch refers to the ways in which programming computer games influenced hobbyists’ self-expression. Švelch sees coding acts as part of a meritocratic system inherent in computer hobbyism, whereby users achieved recognition from their peers based on the skillfulness of the programs they created (see also Reunanen 2017). Coding acts included not only the actual programming but also the publishing and distribution of these programs.

This research differs from previous work in that we have systematically reviewed the program listings published in computer magazines in one country to create a preliminary picture of general phenomena. Unlike many other studies, we focus specifically on game listings. Similar large-scale research has not been conducted in other countries, so in this article, we are unable to compare the situation in Finland to international developments. For example, we are unable to assess whether the same types of listings were published in Finland as elsewhere or whether the creators of the listings were similar to those in other countries. However, it can nonetheless be assumed that Finland’s situation did not significantly differ from other similarly sized Western countries; however, at the same time, Finland’s press scene was unique in many ways: some magazines in Finland enjoyed an exceptionally large circulation and their revenue was largely based on annual subscriptions, not single-issue sales. Additionally, the popularity of different machines varied somewhat from country to country, depending on the investments made by various national importers and retailers.

Publication Forums and Research Methodology

Our research material consists of 1,290 program listings published in 11 computer magazines.[7] We have classified 454 of these as games or game-like entertainment programs, although sometimes the boundary between a game and another type of entertainment program is blurred. Our material includes the majority of all program listings published in Finnish magazines. Finding every program listing ever published in the country is a near impossible task, as individual listings were also published in the 1980s in magazines that otherwise did not deal with computing or gaming. Additionally, we excluded from our material short subprograms of just a few lines and corrections of previous publications; we focused instead on complete programs, utilities and more extensive program routines.[8] We collected the material from the listing supplements of magazines, columns on programming, article series and listings published in club sections. For this reason, we did not include, for example, Mikro, which began in 1983 as Finland’s first microcomputer magazine (later MikroPC) and published only a few individual program listings or parts of them in its early years in programming articles. One of these, published as part of a larger section on games, described how to program a space shooter game (Mikro 1/1984, 55-56: Anders Råberg: ‘Create Your Own Space Game’).

Our material also does not include listings published in smaller local club magazines, as these are rarely found in university library collections or digitised online. Exceptions include the Vikki magazine of the VIC club in the Helsinki area and Tieturi from the 1800 Users’ Club of Telmac users, as well as the association and hobbyist publication Micropost, which were available. In addition to magazines, program listings were published in books but these are not however included in our material.

We have reviewed all issues of the examined magazines either using their digitised versions or by browsing printed copies. We have tabulated the program listings and recorded the following details: the publication channel and date, the name of the program creator as well as the name and type of the program (game, entertainment, graphics, music, utility). We also wrote a short description of the content, selected quotes from the program presentations and noted specific research-related observations. After basic tabulation, we calculated the relative proportions of different program types and computer brands and identified individuals who published programs in different magazines.

Our investigation is founded on basic research in game and media history, where the key focus is on compiling and thoroughly reviewing a large empirical dataset. Reviewing the material means reading, organising and comparing different units of the data. There is no specific methodological name for this approach, though it can well be referred to as historical-qualitative research. However, compared to many other historical studies, the source material in this case forms a relatively cohesive whole, even though it comes from a diversity of magazines.[9]

Our approach is evident in the fact that we intentionally list a large number of games and their creators in the article. The reason for this is that among the creators of the game listings are individuals who are known from other areas of Finnish game or computing history and further, many significant authors of the listings have not been previously acknowledged in research or popular works on game history, even though they deserve recognition. Similarly, compared to commercial game publications, hobbyist publications and game listings have received scant attention in research and there is little previous background knowledge of the types of games published as listings and how they were named.

Content Changes in Game Listings

Game content can be reviewed magazine by magazine, comparing their different emphases. Another possible approach is to examine the content chronologically on a general level. We use both methods but emphasise the latter. This approach makes it easier to observe changes in computer hobbies and gaming cultures from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. When reviewing all game listings chronologically, the period under investigation can be divided into three parts: 1) the early years of publishing from 1978 to 1983; 2) a shift in the popularity of magazine from 1984 to 1985; and 3) the decline in game listings from 1986 to 1989. Next, we will examine these periods.

The Early Phase of Game Listings

The first game listing found in our material was published in Elektroniikka (Electronics) magazine in early 1978. Elektroniikka’s listings included digital versions of classic or relatively new board and card games, such as Mastermind[10], Ventti (Vingt-et-un) and Jätkänshakki (Tic-tac-toe), as well as listings clearly inspired by video games such as Christian de Gozinsky’s Move Loop or Ansapeli (Trap Game) (Elektroniikka 4/1978) and Jan-Erik Nyström’s Miinakenttä (Minefield) (Elektroniikka 7/1978). In some cases, we were unable to determine the original inspiration for the listings. The final game listings published in Elektroniikka, Seppo Kamppikoski’s Jätkänshakki and Richard Eller’s Mastermind, appeared at the end of 1980 and the beginning of 1981 (Elektroniikka 22/1980; 5/1981).

Another early publisher was Prosessori. Most of its early game listings were computer versions of Hangman or various board and card games, such as Othello, Mastermind and Ventti (Vingt-et-un), with occasional outer space, sports or shooting games. The number of game listings in Prosessori began to increase at the end of 1982 and, by 1983, over half of the listings published in the magazine were games. By that time, the game listings in Elektroniikka had practically ceased. Elektroniikka’s hobby club column focused almost entirely on Telmac and related machines, with listings for Telmac computers continuing in Tieturi club magazine between 1982 and 1984. Prosessori, on the other hand, published program listings for a variety of computer types and brands, including the Commodore PET and VIC-20, Apple II, TRS-80 and Sinclair ZX-81. Some of these computers were more expensive (PET, Apple II), while others were cheaper home microcomputers (ZX-81, VIC-20). From the end of 1982 onward, the range of game themes in Prosessori broadened. In addition to traditional board and card games, more complex games were published, such as Ismo J. Reitmaa’s Rata-ajo (Track Race) for the VIC-20 and Jan-Erik Nyström’s Casino Adventure for the TRS-80 (Prosessori 11/1982, see Figure 1).

Game listings were also published in Tietokone (Computer) magazine, Poke & Peek! and Micropost starting in 1983. That year, eight out of the 13 program listings in Tietokone were games. Similarly, 16 out of 18 listings in Micropost were also games. Many of the game listings in Micropost were created by a few recurring contributors and the magazine’s editors.[11] The games in Micropost in 1983 were mostly clone versions[12] of commercial video games, often space games or popular titles of the time, such as Breakout, Pong or Pac-Man, which made for the Commodore VIC-20 and Sinclair ZX-81.

The Commodore distributor PCI-Data’s Poke & Peek! focused almost exclusively on utility programs. Only one of the four program listings in 1983 was a game, the Air Defence game previously published in the U.S. magazine Compute!, which Poke & Peek! (2/1983, 5) advertised with the phrase, ‘The VIC air defence game offers a new perspective on national defence’.[13]

The early game listings often took inspiration not only from board and card games but also from arcade games. Many ‘space games’ had commercial or thematic inspirations, such as Lunar Lander (1979), Asteroids (1979), Space Invaders (1978) and Defender (1981). The ‘maze game’, ‘labyrinth game’, or ‘guzzle game’, which began to appear between 1983 and 1984, typically referred to Pac-Man. These early game listings were often named after their gameplay mechanics or themes. Pac-Man was released as an arcade game in the spring of 1980 and over the next few years, it spread worldwide. In 1982, Atari released Pac-Man for its 2600 home video game console and Pac-Man became one of the most recognisable symbols of video game culture, inspiring enthusiasts to create their own versions (Saarikoski et al., 2017). These hobbyists would often name their versions after their inspirations, either by directly referencing the original game names or by creating wordplays, such as Antti Hakkarainen’s Zac-Man for the VIC (Tietokone 1/1984), Ari Kilpeläinen’s ZX-Man, and Reima Mäkinen’s Pac-Nam (Micropost 3/1983).

In outer space games, there were space stations, space guns, meteor defence, warfare as well as alien and UFO attacks: themes familiar not only from commercial video games but also from movies, TV shows and science fiction literature.

The game Snake was also frequently cloned. The earliest domestic versions we have found were published in 1984, although the history of this game type extends back to the late 1970s.[14] The Snake game became famous in the late 1990s on Nokia mobile phones, but the Snakes, Worms and other similar games of the early 1980s were based on the Blockade arcade video game released by Gremlin in 1976 and the Worm games were published on the CLOAD magazine’s accompanying cassette in 1979, originally programmed for the TRS-80 (see MikroBitti 2/1987). Soon after, versions of the game were quickly made for other platforms, too.

A somewhat different game from the early years was Ari Kilpeläinen’s Shot-down revolver duel, published in Micropost 1/1983. However, this too was based on the well-known duel game genre, which had its roots not only in real-life duels but also in the electromechanical devices found in amusement parks and the descendants of Gun Fight, an arcade video game introduced by Japan’s Taito in 1975. These types of western-themed games were later published for home computers in the early 1980s.

In addition to games, the most common leisure and entertainment programs were biorhythm applications, which were part of wider an international trend.[15] The pseudoscientific idea of biorhythms based on a person’s birthdate was invented in the early 20th century and popularised in the 1970s when biorhythm charts were created for calculators, mainframe computers and coin-operated machines in public places. Programming a biorhythm application for home computers was relatively easy and were published as listings for many home computers in Finland, first for Telmac, Sinclair Spectrum and the rarer Sirius 1, but surprisingly only from late 1983 onward. Alongside biorhythm applications, users also created single listings for things such as palm reading and, only somewhat later, reaction testers became typical entertainment programs.

Another popular type of entertainment program involved coding tools designed for gambling, betting and sports enthusiasts. These listings were not games but rather had game-like elements or were used to optimise gaming experiences. Such programs were published for various platforms, from the popular C64 to the rarer Memotech. The majority of betting-related listings were for the Finnish national betting company Veikkaus’s games. These included a statistics program for analysing football teams’ performance, a system program for Vakioveikkaus (sports pool betting) and a system check program for rake betting systems (Prosessori 12/1983; Printti 20/1985; 18/1987). Numerous programs were also developed for horse racing (MikroBitti 1/1985; 9/1989). However, the most popular programs, according to quantity at least, were various lottery number generators, which first appeared in the early 1980s (Prosessori 2/1982; Tieturi 5/82; MikroBitti 1/1984; Tietokone 4/1984; Printti 20/1985).[16]

From Breakthrough to Decline

The launch of MikroBitti in April 1984 marked a turning point for game listings. Over the next two years, the number of such publications peaked. During this time, there was a clear demand for listings and MikroBitti served as a unifying medium with wide circulation, attracting game listers. Starting from issue 3/1985, MikroBitti began awarding the best listings with a supplementary 500-Finnish mark reward, which was later increased to 1,000 and later 1,500 marks.[17] On the other hand, MikroBitti’s entry into the magazine market led other publications to reduce or cease the publishing of game listings, leading them to focus instead on utility programs. For instance, in 1984, Tietokone published a large number of game and entertainment program listings (40 games and 27 utilities), but in the following years, the magazine only published utility programs making only a few exceptions for PC-compatible computers. Already in the summer of 1984, Jyrki J.J. Kasvi’s mathematical program for calculating derivatives and integrals was advertised with the headline: ‘Forget games, try math on the Vic’ (Tietokone 6-7/1984).

In 1984, Tietokone’s game and entertainment program listings were made for various computer types such as the Sinclair ZX-81 and Spectrum, VIC-20, C64, TRS-80, Apple II, Oric-1 as well as the Swedish Luxor ABC-80 and its ABC-800 version. Along with games, Tietokone also published biorhythm programs such as Jari Latvanen’s version for the rare Victor 9000/Sirius 1 (Tietokone 8/1984).[18]

Tietokone’s game listings included several Pac-Man-inspired maze games, as well as space-themed games. Other notable listings included Heikki Kyllönen’s snake game Luikero (Tietokone 2/1984, for the Spectrum), Jan-Erik Nyström’s Space Adventure for the TRS-80 Model I (Tietokone 4/1984), which was based on Penguin Software’s The Quest (1983) and Tuomas Lepola’s VIC-20 game Muurarin vatsahaava (The Mason’s Ulcer) in which a mason builds a brick wall but cannonballs destroy it (Tietokone 9/1984). In addition, Tietokone published Arto Kytöhonka’s Mielenylennysohjelma (Mind-Uplifting Program), a BASIC-language program that allowed users to create their own therapy programs (Tietokone 9/1984).

MikroBitti also published game and program listings for a wide variety of home computers and occasionally organised game programming competitions, publishing the results as listings. During this period, the market saw an explosion of different home computers. In addition to previously mentioned models, MikroBitti featured listings for Salora Fellow and Manager, Oric-1 and its successor Atmos, Atari XL, Dragon, Sega and Sharp models. Mattel’s Aquarius I and II home computers each had one published listing.

During MikroBitti’s first two years, game listings were dominated by outer space games involving landings on celestial bodies or defending bases against attackers. Another popular theme surrounded the computer versions of board and card games as well as mechanical games, with non-digital game adaptations widely published in other magazines, too. Notable examples include listings for the One-Armed Bandit (fruit machine) (MikroBitti 1/1986; 9/1986), Blackjack (MikroBitti 5/1985; 6-7/1986), Othello (MikroBitti 9/1985; 11/1986), Towers of Hanoi (MikroBitti 3/1983; 9/1988), Nine Men’s Morris (MikroBitti 9/1985; 9/1987, and Mastermind (MikroBitti 9/1986; 3/1987). Surprisingly, no listings for chess were ever published, likely because the game’s complexity would have made the listing too lengthy. Sports games were also common, though more simplistic compared to commercial versions, focusing on individual sports like slalom skiing, ski jumping, javelin throwing and shot put (MikroBitti 1/1984; 1/1985; 8/1985; 1/1987).

Even Printti magazine published a few sports game listings early on, mainly for Spectravideo models. One notable release was Aki Rimpiläinen’s unnamed game that humorously depicted the failure of a Finnish athlete at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics (Printti 1/1985).[19] Rimpiläinen also created a two-part athletics game, Athletics, which was ported to MSX (Printti 19/1985; 20/1985). Overall, games made up only a small portion of Printti’s listings, with only 10 out of its 68 listings in 1985 being games.

By the mid-1980s, listings in MikroBitti began to decline, with most games being developed for popular 8-bit home computers such as the C64[20], Sinclair Spectrum, Spectravideo/MSX and Amstrad CPC. By 1987, the final VIC-20 games were published. Listings for Commodore’s newer models like the C16 and C128 began to appear, though these were commercially less successful. Meanwhile, the 16-bit Amiga and Atari ST platforms began to gain traction and the final listings for Amiga were published in 1989. The rise of 16-bit computers could be seen in the few program listings made for the Atari ST and IBM-compatible PCs. It doesn’t really look like publishing game and software listings was meant to support the use of rarer machines. Instead, moderately popular computers—especially the Amstrad and Spectravideo/MSX—were overrepresented in game listings compared to the market leader, the C64, during the late 1980s. These machines had active user communities, but far fewer commercial games or pirated versions were available for them compared to Commodore 64, “the computer of the republic.”[21]

In 1987, Sanoma’s subsidiary Tecnopress Oy launched C-lehti, a companion magazine to MikroBitti that focused exclusively on Commodore machines. The magazine didn’t have a separate program listing section, but it did feature several columns and series about programming and computer building/modding.[22] Its focus was more on practical software. Between 1987 and 1990, the magazine only published three game listings: Jukka Tapanimäki’s Uridium clone Minidium (1/1987), the editorial team’s simple time-killer Reaction Test (3/1988), and Risto Paasivirta’s Breakout clone PingPong (2/1989). The magazine also published a utility program related to gaming: Inhoword, which listed every word understood by the text parsers in American studio Infocom’s adventure games (5/1988).[23] On the other hand, C-lehti ran a lot of listings for the C64, aimed at beginner game developers. These focused heavily on different graphical effects. Whereas MikroBitti only ever published a handful of Amiga listings, C-lehti ran several dozen. The number of Amiga listings grew as the C64 became technically outdated. The last program listings for the C64 appeared in 1991, less than a year before C-lehti shut down.[24]

The themes of the game publications stayed much the same in the final years of the listings. They still included home-made versions of commercial games, as well as computer versions of board, card, and other traditional games. In addition to the ones already mentioned, MikroBitti published computer versions of Poker, Solitaire, Roulette, and even Bolero (MikroBitti 12/1987; 12/1988; 9/1988; 2/1989). When MikroBitti introduced its first listings for the Atari ST in 1988–1989, they included a space shooter, a biorhythm program, and a digital spin on the global puzzle craze of the 1980s, the Rubik’s Cube (MikroBitti 4/1988; 2/1989; 6/1989). There were also a few more unusual themes. For example, in the summer issue of 1986, MikroBitti ran Yoga for the Memotech, programmed by Esko Pentikäinen. It turned out to be the only game ever published for that machine in the magazine. Judging by its description, though, the game had nothing to do with actual yoga—it was more like a version of the board game Go (MikroBitti 6–7/1986). MikroBitti’s listing publications came to an end in the reform made at the turn of 1989–1990, when the magazine shifted toward a more entertainment-focused content strategy (Saarikoski et al. 2019, 21).

Game Listing Creators

In the following will look at the creators of game listings. The group of individuals responsible for these listings was quite large. In MikroBitti alone, game listings created by over 260 different people were published. In total, our research material included 392 game listing creators. We cannot draw conclusions about the creators’ socioeconomic backgrounds or how the listings were distributed across the country. However, based on factors such as the locations of computer clubs, magazine circulation and comparisons to international research (e.g., Švelch 2018; Halvorson 2020), we can assume that game listing creators were present throughout Finland, though likely more prevalent in larger population centres than in smaller towns.

Based on the names, all game listing creators were male, with one exception.[25] In May 1984, Tietokone magazine published a listing for the Memory Game for the VIC-20, created by Johanna Pohjola. The game displayed random sequences of numbers that the player had to memorise and then input. The player could define the length of the number sequences. It is also possible that some female programmers may have used male pseudonyms.

It’s not entirely clear why the gender distribution among programming hobbyists—at least those who published listings—was so male-dominated, especially considering that there were many female programmers in the Finnish computer industry during the 1970s and early 1980s. However, men still dominated in leadership roles and most public appearances related to the computer industry (Vehviläinen 1996; Suominen 2003, 127–158; Švelch 2018, 78).

It seems that the gender divide in computer hobbyism more closely followed the traditions of technical tinkering rather than professional computing, which were also highly gendered. Technical tinkering, along with the creation of new inventions, was viewed as boys’ and men’s hobby, often associated with a fascination for technology, concepts of masculinity, male camaraderie and forms of gaining recognition (Männistö-Funk 2016, 34–35; for microcomputer hobby contexts and gender, see e.g., Saarikoski 2004, 169–179; Švelch 2018, 77–81). The gender divide was also evident in the readership: 98% of MikroBitti subscribers were male, and in the UK, over 90% of computer hobbyist magazine readers were men (Saarikoski 2004, 178–179).

Individual game listing creators typically did not publish multiple games. In MikroBitti, for example, the vast majority only published a single game. This was also true for many other magazines, with the exception of smaller publications such as Micropost, where a few key editors and contributors were responsible for the games. Only a few creators managed to publish more than two game listings in MikroBitti.[26] This usually happened when a person made programs for a rarer computer, though a few Commodore programmers also managed to publish multiple games. Jorma Jaakkola had four game listings in MikroBitti: a computer version of the Finnish card game Maija (Black Mary) (MikroBitti 9/1985), the space game Super Space (MikroBitti 6–7/1986), the snake game Luikero (MikroBitti 6–7/1987) and the adventure game Adrian (MikroBitti 10/1985), which was awarded Game of the Month.

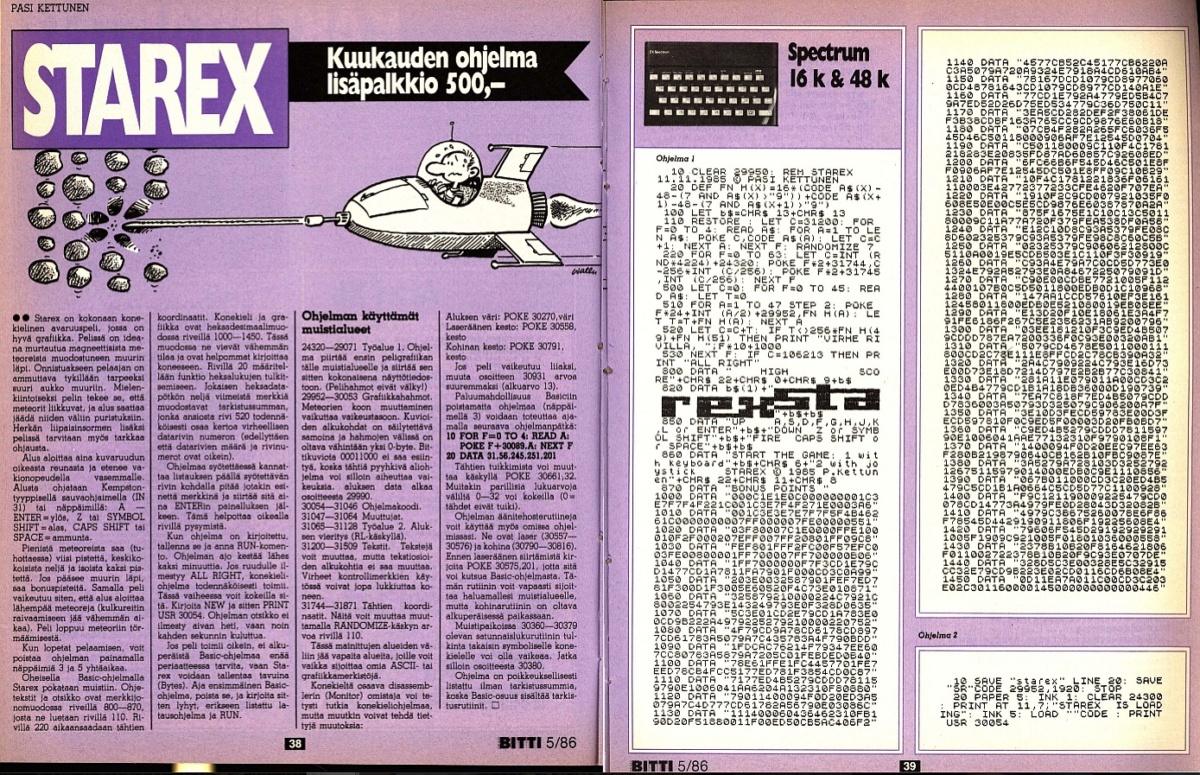

Pasi Kettunen had six games published in MikroBitti: five for the Sinclair Spectrum and one for the MSX (MikroBitti 6-7/1985; 2/1986; 5/1986; 6-7/1987; 3/1987). His outer space game Starex for the Spectrum received a bonus prize for being Game of the Month (see Figure 9), as did his Skyfox game for the MSX. Kettunen also published a graphics-related utility (MikroBitti 9/1987) and placed high in Tekniikan Maailma’s programming competition in 1984 with his program Marsu (Guinea Pig), although no listings of his were published in the magazine (TM 12/1984, 103). Heikki Mäenpää created four PC games during the ‘late era’ of MikroBitti game listings between 1987 and 1989. Among them were the PC-Flight flight simulator (MikroBitti 9/1987), the car game Keke, named after Finnish Formula one driver Keijo “Keke” Rosberg (MikroBitti 10/1987) as well as Lantinheitto (Toss-up) (MikroBitti 1/1988). Mäenpää’s PC Billiards was awarded Game of the Month (MikroBitti 6-7/1989).

Towards the final years during which game listings were published, Timo Poikela created three MSX games. One of them was Zig Zag Joe, described as a ‘relaxing Pac-Man-type game that works both hemispheres of the brain, without forgetting your eyes’. (MikroBitti 11/1989). Mika Silvola programmed a computer version of the Towers of Hanoi for the Spectrum (MikroBitti 9/1988), the space game Hyperion (MikroBitti 1/1986) and a game called Reaktori in which the player defends a nuclear reactor from missile attacks (MikroBitti 10/1987). Games such as Reaktori, drawing on Cold War themes, were relatively rarely published.

One of Jouni Suutarinen’s three games for the Sharp MZ series, Hyppivä Jubert (MikroBitti 4/1984), based on its name, seems to be a version of the arcade game Qbert*, released in 1982. In addition, Suutarinen published Temple, with an Indiana Jones theme and the fighting game Ninjamestarit (Ninja Masters) (MikroBitti 3/1985; 4/1988). Eero Taipale coded two versions of the card game Ventti (Vingt-et-un) for the Amstrad (MikroBitti 5/1985; 6-7/1986), one of which won the Amstrad category in MikroBitti’s Ventti programming competition. He also developed a computer version of Othello (MikroBitti 11/1988).

Jouko Tammela’s four C64 game publications appeared in MikroBitti’s early years. This number is significant, as the C64, Finland’s most popular home computer, likely had such a large number of listings from various developers that getting one’s own game published was more challenging than for programs designed for other computers. Among Tammela’s games were the air shooting game Kone (Plane) and the two-player game Muurinrakennuspeli (Building a Wall) (MikroBitti 4/1984; 2/1985). Petri Tynkkynen’s three VIC-20 games also reflected the popular themes of their time. Tynkkynen made the ski jumping game Scivic-jump, the shooting game Alien Rush and the Knight Rider game based on the TV series (MikroBitti 11/1985; 12/1985; 2/1986). The popular TV series Knight Rider also inspired amateur programmers, despite the fact that there already was a commercial game based on the show. One such game was Janne Uurinmäki’s KITT (MikroBitti 8/1985) where the player jumps a car over various obstacles.

Some game developers imitated commercial game productions and attributed their games to fictional or unregistered software companies (see also Švelch 2018). These unique game studio names were often modifications of the developers’ own names, references to computer culture, or inside jokes. Developers for MikroBitti included Sikala Software (Piggery Software), Silly Silicon Software, Jarisoft and Jansoft (from the first names Jari and Jan) (MikroBitti 5/1985; 2/1986; 3/1986; 5/1987).

Apart from MikroBitti, multiple developers also published in other magazines. Jan-Erik Nyström, for instance, frequently wrote games for the rare TSR-80 computer. His first was Tähtien sota (Star Wars), published in Prosessori in May 1981, followed by Mottipeli (Pocket or Siege game)in August of the same year, and the ‘adventure game’ Casino Adventure in November 1982, which was described as transporting the player to a ‘typical “American world”’ (see Figure 1). Nyström also published the adventure game Space Adventure, Labyrintti (Labyrinth) and a computer version of the dice game Yatzy in Tietokone (4/1984; 9/1984; 12/1984). In MikroBitti (3/1984), Nyström also released Taikurin linna (Wizard’s Castle) at the end of 1984, with instructions on how to adapt the game for other machines. Nyström seemed to specialise in adventure games, which set him apart from other early Finnish amateur game programmers. We cannot be completely sure if it was the same person, but Jan-Erik Nyström had already published listings for Telmac machines and similar systems in 1978 in Elektroniikka magazine (see Figure 2).

Ismo Rakkolainen[27], for his part, created programs for the Sinclair ZX-81. In Prosessori (9/1983; 12/1983), he published Tukikohta (the Base), a Lunar Lander-type game, Reaktiotesteri (Reaction Tester) and a slalom game for the ZX-81in Tietokone (9/1983). Ismo J. Reitmaa was a rare game listing publisher, creating entertainment and game listings for different publishers’ magazines. His first game, Rata-ajo (Track Racing) for the VIC-20, appeared in Prosessori (11/1982) published by Tecnopress, followed by Avaruustykki (Space Cannon) in Tietokone (9/1983) from the same publisher. Reitmaa then transitioned to Printti mgazine, published by A-lehdet, where he released two VIC-20 games: the space combat game Törmäily (Collision) and a computer version of Yksikätinen rosvo (One-Armed Bandit), (Printti 20/1985). Reitmaa also published Linnanmuurilla (Castle Wall) for the Commodore 16 in MikroBitti (6–7/1986).

Unknown or known authors?

A significant portion of the contributors to game listings were ordinary game and computer enthusiasts. Among them, a few standout individuals were active in specific computer brands or programmers who became known later for their commercial game releases. For example, Raimo Suonio, who is credited with creating Finland’s first commercial game, the chess game Chesmac in 1979, published an add-on for the game in Elektroniikka magazine (1/1980), which introduced a feature for changing the difficulty level mid-game and added a save option.[28] Sampo Suvisaari, who released three Bomulus games through the commercial publisher Teknopiste, also frequently published his program listings in Printti magazine.[29] His listings first appeared in the MSX-club column, after which he began contributing a series of extensive articles on machine language graphics. Suvisaari’s listings, typical of Printti, were utility programs rather than games but many were nonetheless related to game development, such as implementing moving graphic elements or sprites. Stavros Fasoulas, nicknamed the ‘Paavo Nurmi of computer games’,[30] published his first game, a Pac-Man clone, in the first issue of MikroBitti (1/1984) (see more in Saarikoski et al., 2017). Fasoulas’s Sanxion (1986) was the first game by a Finnish designer to achieve international distribution.

Galactic Guard for the Oric-1 and NumberBumber for the C-64, both created by Pasi Hytönen, were published in MikroBitti (3/1984; 9/1986), the latter described as a version of an earlier puzzle game made for Spectravideo. Hytönen also won a programming competition organised by Tekniikan Maailma (14/1984, 32–34) with his game Arttu (Arthur) for the Oric-1, which was described as ‘a great mix of strategy, maze, and destruction game’.[31] Hytönen later became famous for the game Uuno Turhapuro muuttaa maalle (1986), based on a film of the same name, which became the last and most commercially successful game release from the Finnish game and software publisher Amersoft (Kuorikoski 2014, 15–16; Pasanen & Suominen 2018). Hytönen also wrote a column called Pelinikkarin Päiväkirja (The Game Hacker’s Diary) for C-lehti (1987–1989), which offered graphical effects programs and routines for novice game developers, using the C64 as the platform. Short demos were also available for these programs.

In addition to Fasoulas, Jukka Tapanimäki also released his games through an international publisher. Tapanimäki contributed to MikroBitti and C-lehti. His first game, the 3D shooting game Monolith, was published in MikroBitti (6–7/1986) and awarded Program of the Month. As previously mentioned, Minidium, inspired by the international hit game Uridium, appeared in C-lehti (1/1987). Tapanimäki also shared game development tips in articles he penned for C-lehti. He later took over Hytönen’s column from issue 5/1989 onwards.

Mikko Helevä, whose Golfmaster game was published by the British company Hewson in 1987, had his space game Space Master featured in MikroBitti (2/1987). Space Master was awarded Program of the Month, and Helevä placed second in MikroBitti’s programming competition, behind Tapanimäki (Kuorikoski 2014, 29). There are other pioneers of Finnish commercial game releases whose works can be found among the program listings in computer magazines of the era. For example, Finnish company Triosoft released Olli Kainulainen’s Talvisota (Winter War) for the MSX in 1987. A few years earlier, Kainulainen had developed Sheriffi: Revolverisankari Lännestä (Sheriff: A Revolver Hero from the West), a duelling game in collaboration with Heikki Lappalainen, reflecting his interest in historically-themed games (MikroBitti 10/1985). Finnish game music pioneer Jori Olkkonen (now Petrik Salovaara) published several utility programs in C-lehti, themost notable being MegaSound, which he used to create music for commercial games (C-lehti 5/1988).

Juha Ojaniemi, brother of Simo Ojaniemi, the creator of Amersoft’s first game releases Mehulinja (Juice Line) and Raharuhtinas (Money Prince), was involved in programming Raharuhtinas, as he recounted in 2019. In addition to a program listing, Juha Ojaniemi wrote articles for Poke & Peek! magazine and published his listings in the Vikki magazine for VIC-20 users. These included his Ristinolla (Tic-tac-toe) version, games such Virgo, FASP and Hit and Run, as well as an unnamed joystick-controlled game, and some drawing and graphics programs (see e.g., Vikki 1/1983; 4/1983; 5/1983; 7/1983).

Other contributors to program listings were individuals known for their achievements in other fields. Pekka Tolonen, who created the therapy conversation simulator Kalle Kotipsykiatri, also became known as a pioneer in electronic music (Saarikoski et al., 2019). For his part, poet and nonfiction author Arto Kytöhonka published two program listings (Tietokone 9/1984; 11/1984) and was an active computer enthusiast, writing about hacking as a passionate hobby. Screenwriter and CEO of Helsinki-filmi, Aleksi Bardy, published Igor, a program for learning Cyrillic alphabets and a BASIC extension for Spectravideo in Printti (6/1987; 12/1987). Jyrki J. J. Kasvi, later known for his work in promoting the information society and as a Member of Finnish Parliament, published games and utility programs in Prosessori and Tietokone magazines. He also contributed to MikroBitti and Pelit magazines. Kasvi’s only publication in Prosessori magazine (12/1982) was Katko or Viimeinen Tikki (Last Trick), a computer version of a card game for the VIC-20. In Tietokone magazine (11/1983), Kasvi’s game Romuralli (Demolition Derby) was published for the VIC. Petteri Järvinen, a well-known IT author, also contributed listings, though most were utility programs, with the exception of Hirsipuu, a computer version of Hangman for the Apple II, published in Prosessori in November 1982 and Laiskan miehen lotto (Lazy Man’s Lotto), a lotto number generator for PC-compatible machines, published in Tietokone in summer 1985.

Harri Oinas-Kukkonen, now a professor of computer science at the University of Oulu, developed two games for the Sharp MZ-700, Nopeustesteri (Reaction Tester) and Pujottelu (Slalom), published in MikroBitti (6-7/1985; 10/1985). Petri Lankoski, now a game researcher and professor in Sweden, had his game Ansapolku (Trap Path) for the Spectrum published in Tietokone in April 1984. The game involved navigating from the left to the right side of the screen while avoiding obstacles.

Thus, not many enthusiasts published programs across multiple magazines or with different publishers. Some movement occurred from Prosessori and Tietokone to MikroBitti, and as club columns moved from one magazine to another, their regular contributors followed. However, there was little crossover between different publishers, such as MikroBitti and Printti, though, in addition to the aforementioned Ismo J. Reitmaa, Heinrich Pesch also published in both magazines. In MikroBitti, Pesch‘s programs were C64 utilities and versions of the Game of Life simulation (see e.g., MikroBitti 4/1986). In Printti, he published example programs for the LOGO programming language, often in collaboration with Susanna Pesch.

Conclusion

The reasons behind a magazine’s motivations to publish game and other software listings were manifold. As noted in previous research, the listings provided cheap content for the publications, serving the needs of their readership, especially during the nascent stages of home computer proliferation when commercial software was not yet widely available for all computer models. Another key reason for publishing these listings was the creation and maintenance of a hobbyist community. This sentiment was particularly evident in club magazines and columns but also in commercial publications. While club magazines and columns typically focused on a single computer brand or model, computer magazines aimed to foster a broader hobbyist community and establish a dialogue between the editorial staff and their readers. However, it is essential to ask what kinds of communities were being built through these software listings. With the exception of Johanna Pohjola, it appears that all the creators of the published game listings were male, and even among the authors of utility software listings, there were very few women. In this respect, the computer hobbyism of the time was highly gendered.

Programming skills were a hallmark of hobbyists in the mid-1980s. There was an implicit expectation—both communally and even socially—that computer hobbyists possessed some programming skills or at least aspired to acquire them. Game-listing publications served as tools for practicing programming. Program examples and their documentation were often created with the expectation that the reader would modify the program themselves, thereby gaining insights into how it worked. However, it is difficult to say how often this actually occurred. In this case, we also need to ask what type of programming was being practiced—and for what purpose.

In the case of games, practicing programming involved understanding the logic of how programs operated. Many of the published game listings were more or less direct clones of popular games. Cloning—imitating and replicating earlier games—tied game listings to the broader cultural context of digital gaming. This was a widespread practice in the 1980s, particularly with early-generation consoles and arcade games. Both commercial entities and computer hobbyists engaged in the practice. Clones helped games spread across different platforms (see, for example, Swalwell 2009). Many of the clone game listings in the data were based on popular arcade games whose mechanics had already proven to be effective. This allowed the authors of the listings to focus on writing code rather than refining gameplay. The familiarity of the original game also aided the clone, as players immediately knew what kind of game it was.

Computer versions of board games, card games and games like roulette and slot machines were also common. By creating these, hobbyists sought to understand game mechanics and their operations in various forms. This can be seen as analogous to practicing visual art techniques by copying masterpieces. It can also be interpreted as an attempt at reverse engineering, where one reconstructs an existing end-product using their own resources, without knowing the original ‘formula’ or composition.

Following Švelch (2018), it can also be noted that game listing publications were ‘coding acts’ motivated by a desire for recognition or status. This ties into the concept of subcultural capital—culturally bound knowledge that brings respect and status within a particular subculture (see Thornton 1995). Programming hobbyists gained attention within their communities through their listings, which could even serve as stepping stones to a career in the game or software industry. Listings also contributed to the authors’ credibility as IT professionals, for instance as writers of technical literature, editors or contributors to computer magazines. In some cases, individuals involved in commercial game production or editorial teams may have highlighted their subcultural capital and status by publishing program listings. For most hobbyists, however, it was likely just a small reward and the satisfaction of seeing their work in print. From the editorial perspective, the motive was to serve the readership by sharing knowledge and tips about programming.

The motivations for creating and publishing software listings shifted over the course of the 1980s. By the end of the decade, the previously mentioned motivations gradually waned. Gaming had established itself as the primary use of popular 8-bit home computers. There were numerous pirate versions of games available, while the quality and playability of game listings never truly competed with commercial games. This undoubtedly affected their popularity outside of programming hobbyist circles. Moreover, by the late 1980s, the most popular computer models had become technically outdated. Programming hobbyists transitioned to newer 16-bit computers, around which communities such as the Finnish demoscene emerged in the 1990s (see Reunanen 2017, 67–71).[32] Publishing program listings was no longer the most practical way to share code. Listings faded from computer magazines, but self-made non-commercial software continued to circulate through other channels, increasingly digitally via computer networks and later the internet.

In this article, we have examined program listings published in Finland through comprehensive research material. Our article highlights how many early Finnish commercial game developers had backgrounds in publishing game listings. Some other notable individuals from the IT or media sectors also published such listings. We have also introduced several individuals who published game listings whose names have not previously come up in discussions of the early stages of Finnish computer game history.

However, we have not analysed the program codes themselves or played the published games. These perspectives could nonetheless be explored in future research. In follow-up studies, more attention should also be given to certain game versions, the development of specific game types or hobbyist interpretations. Additionally, publications that deviated from the mainstream deserve more thorough examination. Furthermore, Finnish hobbyist programming and publishing cultures should be compared to those in other countries.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editorial board and reviewers of Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja (Yearbook of Game Research), as well as Markku Reunanen and Petri Saarikoski for their comments. Thanks to Elina Vaahensalo for tabulating the program listings from Prosessori and Tietokone magazines, and to Anni Vesterinen for tabulating the listings from Tieturi and Vikki magazines. This research was conducted as part of the Research Council of Finland-funded Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies (grant number 312396).

Sources

Magazines

C-lehti 1987–1989.

Elektroniikka 1978–1981.

Elektroniikka & Automaatio 1981–1983.

Micropost 1983–1985.

Mikro 1984.

MikroBitti 1984–1989.

Poke & Peek! 1983–1986.

Printti 1984–1987.

Prosessori 1979–1984.

Tekniikan Maailma 1982–1985.

Tietokone 1984–1990.

Tieturi 1982–1984.

Vikki 1983–1984.

Literature

Ahonen, Jukka. 2019. “Kolme kriisiä ja kansalliset rahapelit: Yhteiskunnallisten murroskausien vaikutus suomalaisen rahapelijärjestelmän muotoutumiseen.” Väitöskirja, Helsingin yliopisto. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-4778-3.

Campbell-Kelly, Martin. 2004. From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry. London: MIT Press.

Campbell-Kelly, Martin. 2007. “The History of the History of Software.” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 29 (4): 40–51.

Fuller, Matthew (toim.). 2008. Software Studies: A Lexicon. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Haddon, Leslie. 1988. “The Roots and Early History of the British Home Computer Market: Origins of the Masculine Micro.” Väitöskirja. Lontoo: Lontoon yliopisto.

Halvorson, Michael J. 2020. Code Nation: Personal Computing and the Learn to Program Movement in America. ACM Books #32. New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

Heikkinen, Tero & Markku Reunanen. 2015. “Once Upon a Time on the Screen – Wild West in Computer and Video Games.” WiderScreen 2015 (1–2). http://widerscreen.fi/numerot/2015-1-2/upon-time-screen-wild-west-computer-video-games/.

Kemeny, John G. & Thomas E. Kurtz. 1964. BASIC: A manual for BASIC: The elementary algebraic language designed for use with the Dartmouth Time Sharing System. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Computation Center.

Kirkpatrick, Graeme. 2012. “Constitutive Tensions of Gaming’s Field: UK Gaming Magazines and the Formation of Gaming Culture, 1981–1995.” Game studies: The international journal of computer game research 12 (1). http://gamestudies.org/1201/articles/kirkpatrick.

Kuorikoski, Juho. 2014. Sinivalkoinen pelikirja. Suomen pelialan kronikka 1984–2014. Sl: Phobos.

Kuorikoski, Juho. 2017. Commodore 64: Tasavallan tietokone. Helsinki: Minerva.

Mackenzie, Adrian. 2008. “Internationalization.” Teoksessa Software Studies: A Lexicon, toimittaja Matthew Fuller, 153–161. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Manovich, Lev. 2013. Software Takes Command. New York: Bloomsbury.

Matilainen, Riitta. 2017. “Production and consumption of recreational gambling in twentieth-century Finland.” Väitöskirja, Helsingin yliopisto: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-3282-6.

Mertala, Pekka, Lauri Palsa & Tomi Slotte Dufva. 2020. “Monilukutaito koodin purkajana: Ehdotus laaja-alaiseksi ohjelmoinnin pedagogiikaksi.” Media & viestintä 43 (1): 21–46. https://doi.org/10.23983/mv.91079.

Montfort, Nick, Patsy Baudoin, John Bell, Ian Bogost, Jeremy Douglass, Mark C. Marino, Michael Mateas, Casey Reas, Mark Sample & Noah Vawter. 2013. 10 PRINT CHR$ (205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Männistö-Funk, Tiina. 2016. “Kipinäinduktorien ja influenssikoneiden tenhosointu: Nuorten kokeilijain ja keksijäin kirja teknologiasuhteen rakentajana.” Tekniikan Waiheita 34 (2): 26–40. https://journal.fi/tekniikanwaiheita/article/view/82282.

Niklas Nylund. 2016. “The early days of Finnish game culture: Game – related discourse in Micropost and Floppy Magazine in the mid-1980s.” Cogent Arts & Humanities 3 (1): 1–18. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23311983.2016.1191124.

Ojaniemi, Juha. 2019. “Tietokoneet ja minä”. https://juha.info/tietokoneet-ja-mina/.

Pasanen, Tero. 2011. “‘Hyökkäys Moskovaan!’ – Tapaus Raid over Moscow Suomen ja Neuvostoliiton välisessä ulkopolitiikassa 1980-luvulla.” Teoksessa Jaakko Suominen, Raine Koskimaa, Frans Mäyrä, Olli Sotamaa & Riikka Turtiainen (toim.) Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja 2011, 1–11. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto. http://www.pelitutkimus.fi/vuosikirja2011/ptvk2011-01.pdf.

Pasanen, Tero & Jaakko Suominen. 2018. “Epäonnistunut yritys suomalaisen digitaalisen peliteollisuuden käynnistämiseksi: Amersoft 1984–1986.” Lähikuva 31 (4): 27–47. https://journal.fi/lahikuva/article/view/77932.

Pudas, Mari. 2016. “Sauli Niinistö opetteli koodaamaan – ‘Haluan, että kilpikonna kääntyy oikealle’.” Iltalehti 19.1.2016. https://www.iltalehti.fi/uutiset/a/2016011920980504

Rautanen, Niila T. 2014. “Micropost syntyi koodaamisen vimmasta”. https://tietokone.ntrautanen.fi/other/micropost2.htm.

Reunanen, Markku. 2014. “How Those Crackers Became Us Demosceners.” Widerscreen 2014 (1–2. http://widerscreen.fi/numerot/2014-1-2/crackers-became-us-demosceners/.

Reunanen, Markku. 2017. “Times of Change in the Demoscene: A Creative Community and Its Relationship with Technology.” Väitöskirja, Turun yliopisto. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-6717-9.

Reunanen, Markku & Manu Pärssinen. 2014. “Chesmac: ensimmäinen suomalainen kaupallinen tietokonepeli – jälleen.” Teoksessa Jaakko Suominen, Raine Koskimaa, Frans Mäyrä, Petri Saarikoski & Olli Sotamaa (toim.) Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja 2014, 76–80. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto.

Saariketo, Minna. 2020. “Kuvitelmia toimijuudesta koodin maisemissa.” Mediatutkimuksen väitöskirja. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-03-1531-3.

Saarikoski, Petri. 2004. Koneen lumo: mikrotietokoneharrastus Suomessa 1970-luvulta 1990-luvun puoliväliin. Turun yliopiston yleisen historian väitöskirja. Nykykulttuurin tutkimuskeskuksen julkaisuja 83. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-7243-1.

Saarikoski, Petri. 2006. “Koneen ja koulun ensikohtaaminen: suomalaisen atk-koulutuksen varhaisvaiheet peruskoulussa ja lukiossa.” Tekniikan Waiheita 24 (3): 5–19. https://journal.fi/tekniikanwaiheita/article/view/63817.

Saarikoski, Petri. 2011. “Kasarisukupolven teknoanimaation perintö.” Widerscreen 2011 (1–2). http://widerscreen.fi/2011-1-2/kasarisukupolven-teknoanimaation-perinto/.

Saarikoski, Petri, Jaakko Suominen & Markku Reunanen. 2017. “Pac-Man for the VIC-20: Game Clones and Program Listings in the Emerging Finnish Home Computer Market.” Well Played Journal 6 (2): 7–31. http://repository.cmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1042&context=etcpress.

Saarikoski, Petri, Markku Reunanen & Jaakko Suominen. 2019. “‘Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa’: Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokoneohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-luvulla.” Tekniikan Waiheita 37 (3): 6–30. https://journal.fi/tekniikanwaiheita/article/view/86772.

Suominen, Jaakko. 2003. Koneen kokemus. Tietoteknistyvä kulttuuri modernisoituvassa Suomessa 1920-luvulta 1970-luvulle. Tampere: Vastapaino.

Suominen, Jaakko. 2018. “Soveltavasta kulttuurintutkimuksesta hybridihumanismiin.” Teoksessa Pilvi Hämeenaho, Tiina Suopajärvi & Johanna Ylipulli (toim.) Soveltava kulttuurintutkimus, 31–54. Tietolipas 259. Helsinki: SKS.

Swalwell, Melanie. 2008. “1980s Home Coding: The Art of Amateur Programming.” Teoksessa Susan Ballard & Stella Brennan (toim.) The Aotearoa Digital Arts Reader, 193–201. Auckland: Aotearoa Digital Arts and Clouds.

Swalwell, Melanie. 2009. “Towards the Preservation of Local Computer Game Software. Challenges, Strategies, Reflections.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 15 (3): 263–279.

Švelch, Jaroslav. 2018. Gaming the Iron Curtain. How Teenagers and Amateurs in Communist Czechoslovakia Claimed the Medium of Computer Games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Švelch, Jaroslav. 2019. “Red Stars, Biorhythms, and Circuit Boards: Do-It-Yourself Aesthetics of Computing and Computer Games in Late Socialist Czechoslovakia.” Teoksessa Aga Skrodzka, Xiaoning Lu & Katarzyna Marciniak (toim.) The Oxford Handbook of Communist Visual Cultures, 136–156. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thornton, Sarah. 1995. Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

Tuomi, Pauliina, Jari Multisilta, Petri Saarikoski & Jaakko Suominen. 2018. “Coding skills as a success for a society.” Education and Information Technologies 23 (1): 419–434.

Vehviläinen, Marja. 1996. “‘Maailmoista ilman naisia’ tietotekniikan sukupuolieroihin.” Teoksessa Merja Kinnunen & Päivi Korvajärvi (toim.) Työelämän sukupuolistavat käytännöt, 143–170. Tampere: Vastapaino.

Notes

[1] BASIC or Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code (Kemeny & Kurtz, 1964. See also Montfort et al., 2013, 157–194).

[2] However, in Finnish club magazines such as Tieturi (1983–1984), printed program listings were not often published. Instead, the magazine issues came with program cassettes compiled by club members (Saarikoski, 2005, 68).

[3] In the United States, for example, game listings had already been published in books since the early 1970s. Michael Halvorson, who studied the history of hobbyist programming in the U.S., notes that David Ahl’s book 101 BASIC Computer Games (1973), which published program listings submitted by users across the U.S. for the DEC PDP minicomputer, became extremely popular and sold tens of thousands of copies. Ahl also created sequels to the book in the late 1970s aimed at microcomputer users, further boosting the popularity of game programming. These books seem to have created a model for the publication process of listings: Ahl tested the games submitted by users, made corrections, if necessary, published the best ones and wrote a short description of each game, noting its usability and technical limitations (Halvorson, 2020, 19, 128–132). A similar editorial process was also used in many Finnish magazines that published program listings.

[4] The term pastime program or entertainment program was a contemporary concept that referred to not only games but also other entertainment programs, such as biorhythm programs, humorous artificial intelligence applications, text generators and so forth.

[5] The demoscene is a subculture of computer enthusiasts that has evolved since the late 1980s, focusing on creating audiovisually impressive and code-optimised program segments.

[6] The concept of coding act or coding action introduced by Švelch has been inspired by John Austin’s and John Searle’s speech act theories as well as game history research and other game studies that emphasise the creativity of hobbyists.

[7] The sources also include general technical magazines such as Tekniikan Maailma, club magazines and a magazine published by Finland’s Commodore importer.

[8] As a result, cheat codes for games published on the Peli-Guru column of C-lehti were not included in the research material.

[9] For methods and materials in historical game research, see, for example, Matilainen (2017, 37). For the concept of basic research in historical studies, see Suominen (2018, 38). Our research method could perhaps also be called an application of data-driven qualitative content analysis, although we have not conducted detailed content-based categorisation or classification. Individual program listings can be thought of as observation units, and the publication data recorded in the table’s columns as coding units on which the analysis is based, but in this case, the coding does not extend much into the listing contents.

[10] Mastermind is a board game developed by Israeli Mordecai Meirowitz in the early 1970s, which can also be played on paper and became popular in Finland around the late 1970s and early 1980s.

[11] Micropost was a fanzine-type publication created by hobbyists, edited by Petri Tuomola and Reima Mäkinen. Game history researcher Niklas Nylund (2018) described its visual style as ‘punk-inspired’. Nylund’s characterisation refers to other subcultural publications of the time, often duplicated using photocopiers. In a later phase, Micropost was published by the Mikromaakarit association. Out of the games published in the magazine, 10 were made for the Sinclair ZX81, 12 for the VIC-20, and two for the Sinclair Spectrum. The program listings in Micropost were created mainly by Sami Inkinen, Tuukka Kalliokoski, Ari Kilpeläinen, Reima Mäkinen and Petri Tuomola.

[12] In this context, the term clone refers to both the archetype of a certain game genre and games whose mechanics or content were directly copied from a previous game.

[13] Similar defence rhetoric was used in MikroBitti (2/1985) a couple of years later in a review of the commercial game Raid Over Moscow. In this review, the reviewer’s innocent remark about an ‘excellent defence game’ sparked accusations of anti-Soviet sentiment and led to a broader game-related controversy (Pasanen, 2011). The program listing in Poke & Peek! did not directly reference the Soviet Union, but the listing’s inspiration may have been the arcade game Missile Command (1980), whose versions appeared for home computers widely in the early 1980s.

[14] This refers to Heikki Kyllönen’s game Luikero, published in Tietokone magazine in February 1984.

[15] Entertainment programs aimed at creating music and graphics are not included in this group of pastime programs.

[16] For the Finnish history of betting games and, for example, the role of the lottery as a popular game in Finland, see Matilainen (2018) and Ahonen (2019).

[17] 500 Finnish marks in 1984 corresponds to approximately 220 euros in current currency (2024) according to the Finnish Bank’s inflation calculator. The cheapest home computers in 1984 cost just under a thousand marks without accessories, but the typical price with mass storage was at least double or triple that. Hit games usually started at a price of 100 marks, and games for PC-compatible systems, as well as for the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST, could cost up to 300 marks per game by the late 1980s.

[18] The biorhythm program created by Latvanen for Sirius was also published in Tekniikan Maailma 14/1984. The Victor/Sirius computer resembled the IBM PC to some extent, but it was not IBM-compatible.

[19] The initial premise of the game is humorous: The Finnish Olympic Committee refuses to cover the return trip of an athlete who failed in the competition and the athlete must run back to Finland. The athlete’s return is hindered by various obstacles, which the player must avoid. The game has a total of five levels.

[20] However, C64 publications primarily focused on utility programs.

[21] Commodore’s importer PCI-Data used the term ‘the computer of the republic’ in ads for the Commodore 64, a period when the device became the most popular home computer in Finland (for ads, see, e.g., MikroBitti, see also Saarikoski 2004; Kuorikoski 2017). Earlier, for example, in Germany, the VIC-20 had been sold with the slogan the ‘Volks Computer’, the people’s computer, likely in reference to the popular slogan of Volkswagen cars.

[22] The utility program listings in the magazine were mainly handled by members of the editorial team: Jukka Marin, Tomi Marin, Pekka Pessi and Pasi Andrejeff. Pasi Hytönen was responsible for the game programming listings, although Jukka Tapanimäki also published a few listings on the subject.

[23] A text parser translates and simplifies the text commands entered by players for the game system.

[24] C-lehti published program listings until its final issue (1/1992), although the number of listings dropped dramatically at the beginning of 1991.

[25] Although we cannot determine the typical age of those who created the listings, based on well-known examples, it seems that the creators were usually slightly under or over 20 years old, though there were also younger and somewhat older hobbyists.

[26] We do not know the exact editorial process for the listings in MikroBitti, nor do we know how many listings were submitted for publication.

[27] Rakkolainen has since been employed as a researcher in human-computer interaction at Tampere University and has been involved in developing, among other things, FogScreen technology. See https://www.tuni.fi/fi/ismo-rakkolainen.

[28] For more about Chesmac, see Reunanen & Pärssinen (2014).

[29] Teknopiste released three Bomulus games for the Spectravideo and MSX in 1985–1986. According to game journalist and non-fiction author Juho Kuorikoski (2014, 23), the Bomulus games were ‘the Tomb Raiders of their time, action spiced with simple problem-solving’.

[30] The title the ‘Paavo Nurmi of Computer Games’, referring to the early 20th century Olympic champion, was given to Fasoulas by Niko Nirvi in his review of the Sanxion game (MikroBitti 12/1986).

[31] Hytönen also developed a game entitiled Little Knight Arthur for the Commodore 64, but it did not find a publisher at the time and was only released a few years ago.

[32] The beginning of the demoscene can be traced back to the mid-1980s and the C64 computer. However, at that time, the demoscene had not yet become its own subculture but was strongly connected to software piracy (Reunanen 2014).